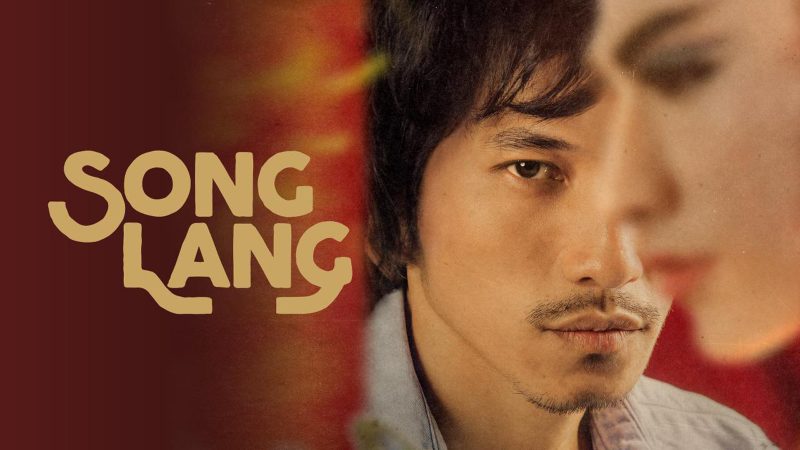

Song Lang, A World of Refugee Memory

by Victoria Huynh

When people write about Little Saigon, they tend to use words like unchanging, static—as if Vietnamese refugees were stuck in the past, suspended in amber as the world turns by.

At the 2019 Philadelphia Asian/American Film Festival, as the lights flickered on to the credits of Song Lang, I felt that disappointment that art often comes with, that of returning to my world after inhabiting another. Some think the past is static. But after journeying to Song Lang‘s rich world of 1980s Saigon, how could I see my people’s past as anything but brilliantly, achingly alive?

Song Lang sets a queer love story in the golden age of cải lương (modern Vietnamese folk opera) that captivated director Leon Lê’s childhood. Watching it feels like wading through memory itself, each frame suffused in hazy, dreamlike tones of golden-orange.

The film begins with Dũng, a child of cải lương performers. His father once said that the song lang (a percussive instrument) represents the rhythm of our lives, guiding performers on their moral path. For a while, that familiar beat has been missing from my life, Dũng thinks. After his mother’s departure and father’s death, he became a gangster who beats truant debtors, mostly struggling, everyday city-dwellers.

But song lang also translates to two men, the play on words intertwining the characters’ love for cải lương with the pull they feel towards each other. The terse, closed-off Dũng finds himself at a theatre, eyes fixed on the prodigious male lead, Linh Phụng. The harsh planes of Dũng’s face soften; a light inside him flickers. The next night, thrust together by circumstance, debt collector and performer become unlikely friends, and love quietly emerges.

*

Like birds flying south, answering some unnamable call, my family would drive hours to attend hội đồng hương, hometown reunions. After basking in laughter, dancing with schoolmates and piling beer cans on the floor, they played love ballads on the way home and told us stories of Vietnam, the country of their memories.

Cải lương feels like an extension of our people’s nostalgia. Its song form vọng cổ literally translates to a longing for the past: a lament for lovers lost, years spent, homes impossibly far away. Singers stray into unaccompanied solos, their voices clear and lonely in the air.

Song Lang itself yearns for an impossible past. Cải lương is now dying, its existence near-unknown to Vietnamese youth. We might blame globalization, but I also think that as my generation strives to create Vietnam’s postwar future, we’re quick to dismiss our parents’ nostalgia.

This generational divide is perhaps more bitterly felt in the diaspora. After losing the Vietnam War, refugees recreated home in Little Saigons everywhere. They still denounce the new regime, build war memorials, and fly the flag of South Vietnam, a country that no longer exists. I watch them and wonder why we still tread in stagnant waters. The war is over. The world has moved forward, so why keep looking back?

When I asked Lê this question at the post-screening Q&A, he sidestepped it with an easy smile. Song Lang doesn’t seek to answer those big questions, he said. It was born simply from his love for cải lương, which he hoped others might share.

Song Lang avoids making value judgments about nostalgia in the ways I’m tempted to. It’s more concerned with how memory serves artistry. Both characters remember love and loss differently: Dũng tries to forget loss through solitude and violence. Linh Phụng wears love like an ill-fitting costume. In cải lương, which distills life’s joys and sorrows into their clearest forms, both approaches falter. Both learn that memory is not a choice, but a journey driven by instinct, an act of time travel.

Queer people, refugees, those displaced from the linearity of the present, who love people and places long gone: we’re always time traveling. We journey between the possible and impossible by way of memory, and art emerges in the crossing.

At the Q&A, Lê emphasized that he never hoped to revive cải lương. He knew no Vietnamese studios would take a film about an irrelevant art form. Yet his love for cải lương, persistent and unfulfilled, kept calling him into memory. “I felt that I had made a promise to cải lương, that someday, I would find a way to honor it. Now, I’ve kept my promise.”

*

After watching Song Lang, I went home to listen to the music that so captivated my family. I tried to imagine walking along the river where cải lương was born. Its melodies clear and winding, rarely shifting from their course. Its plucked harmony dropping like pebbles into a stream.

I listened and tried to see that impossible place where the river meets the sky. Sometimes I think that’s where my family journeys to, in the pause before a memory emerges, in the soft twang before a song begins. They wade through some distant world as I wait here, awash in a memory of a memory.

Even in all that we’ve lost, journeying back means more than simply mourning. When Lê speaks of cải lương, even of its death, his body is animated and his eyes shine. Maybe what I thought was nostalgia is also love in its most earnest form. Maybe we aren’t haunted by the past, but enamored with it. Song Lang lost money in Vietnam but won international acclaim from those who know there’s so much beauty, so much left to learn from looking back.

In the night they share, Dũng and Linh Phụng explore an impossible, beautiful world in which loss might be reconciled, in which love might begin. The night ends, but that’s alright, because the point of time travel isn’t to stay. It’s to return to the present feeling wiser for having made the journey. In remembering, in following the beat of the song lang, both find a way to distill the muddy waters into something clear, filled with light.

Bio

Victoria is originally from San Diego, California. She’s invested in healing justice and Southeast Asian movement work. Her writing has also appeared in Catapult, and she tweets at @victoriatnhuynh.