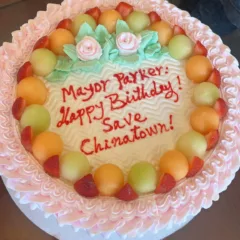

On February 13th, the official Twitter account of OneUnited Bank, the largest Black-owned bank in the United States, debuted their limited edition Black History Month debit card to much uproar. The card in question featured an image of Harriet Tubman appearing to pose in the “Wakanda Forever” stance popularized by the 2018 Marvel movie, Black Panther. Twitter users were quick to lampoon the card for its visual absurdity. However, many also noted the irony of a bank using the likeness of an activist and war hero who fought against chattel slavery, which brought on the advent of modern capitalism. Banks in particular owe their development to the slave trade, as systems of credit were expanded to help plantation owners buy land.

In his exhibition at the Cherry Street Pier, This Is Our Story, Acori Honzo approaches the issue of appropriating African American heroes’ likenesses with a keen awareness of the fine line between commemoration and exploitation. Dodge’s widely-panned Super Bowl Commercial, which featured snippets of a sermon by Martin Luther King Jr., is just one of the many examples of businesses warping historic Black activists’ messages for self-serving aims. Through his artistic practice, Honzo poses an alternative means of remembrance which aspires to educate future generations, rather than pull cash from their wallets.

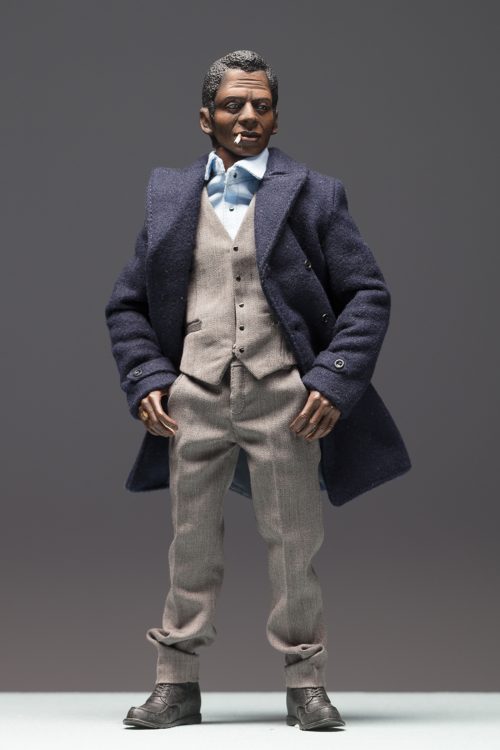

This Is Our Story features a series of dolls sculpted by the artist. The sculptures depict a range of Black historical figures dressed in period clothing, including Tubman, Maya Angelou, and Malcolm X. Spread throughout the exhibition are several large-scale photographs of the dolls taken by Honzo’s fellow artist-in-residence at the Cherry Street Pier, Jim Abbott. These photographs give greater insight into the meticulous detail Honzo put into the dolls which one would not otherwise be able to see given the dolls’ placement behind Plexiglass cases.

It’s this extreme attention to detail that situates Honzo’s practice within broader questions about how our culture chooses to remember and honor Black history. As I toured the intimate studio space, I couldn’t help but imagine the stark contrast between Honzo’s painstaking efforts to incorporate personalized details like the wrinkles on James Baldwin’s forehead or a cigarette in Richard Pryor’s hand and the large Mattel factory machines pumping out thousands of sleek plastic Rosa Parks dolls.

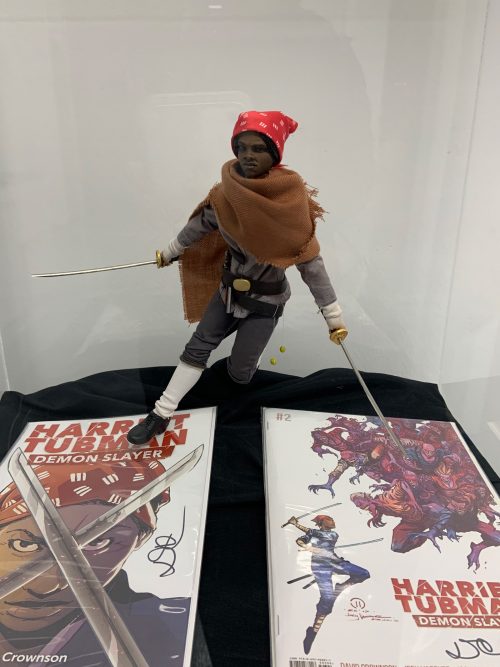

At the same time that Honzo strives to imbue his sculptures with a lifelike quality, he also does not shy away from more imaginative renderings of his subjects. His sculpture of Tubman, namely, is modelled after the depiction of her character in the comic book series, Harriet Tubman: Demon Slayer. While the doll and the accompanying comic book volumes are sensational, these imaginings of Tubman as a daring superhero feel far more apt than a flattened image of her on the front of a plastic debit card. Furthermore, their pairing in this exhibition allows audiences to imagine a future wherein Black history doesn’t get co-opted by corporations whose sole interest is profit. Instead it is put in the care of artists and other creatives who take on the labor of doing right by those who made great sacrifices for the good of their people.

Bio

Kinaya Hassane is the Curatorial Fellow in the Graphic Arts Department at the Library Company of Philadelphia. She enjoys looking at and writing about art of the African Diaspora.