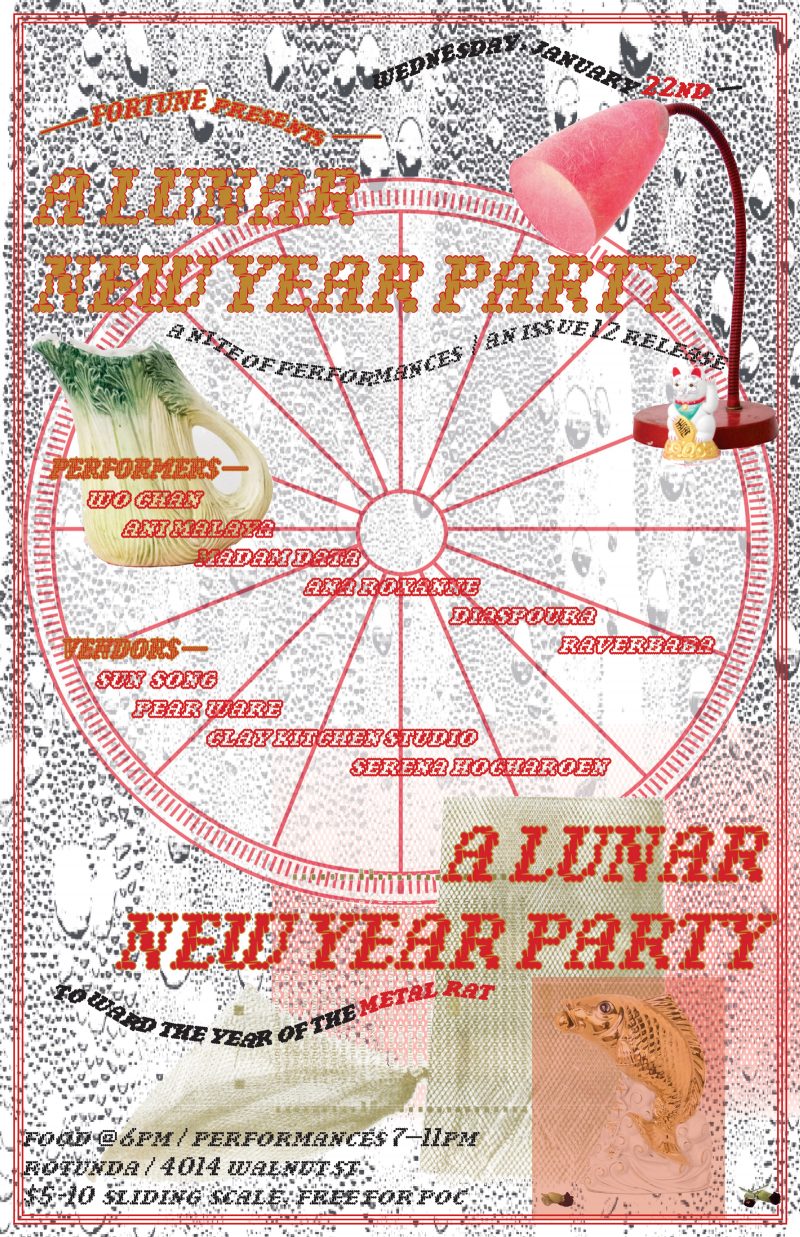

Author’s Preface: FORTUNE is a monthly zine that seeks to uplift voices in the queer Asian diaspora. It was launched and is run by Connie Yu, Andrienne Palchik, and Heidi Ratanavanich. Lunar New Year Celebration: Year of the Rat was a night of performances, vendors, and food, marking FORTUNE’s final issue in their year-long run. It also marked the start of the new lunar calendar—the end of the year of the Pig, and the beginning of the year of the Rat. The event, like the publication, focused on queer Asian-American artists and brought together performers and makers from Philadelphia, New York, California, and South Carolina. The celebration was funded in part by the Leeway Foundation and co-organized with independent curator and organizer Sarah Kim, whose reflections are written here.

A NEW YEAR

For many cultures that attend to the lunar calendar, January 2020 marks not only the end of the Year of the Pig, but also the beginning of a new 12-year zodiac cycle. FORTUNE, a monthly small-run submission-based publication by and for queer Asian publics, will celebrate the end of its year-long run with forms as urgently iterative as they are new for us: a double-issue released by way of a festival, featuring performances by queer Asian artists.WHAT’S ON STAGE

This project, one in a series of gatherings that mark each issue’s release, will be of a scope larger than we’ve been able to produce. Though we make our practice tangible in print, our gatherings do the work of filling in the blanks, of giving life to shared references, of building real kinship amongst our network. This performance festival will feature modes of creative expression that extend beyond expectation of common language. We imagine a distinct and generative space for queer Asian-American folk outside the bounds of text, one rooted in the Asian diasporic cultural traditions of performance, material craft, music, and food.FORTUNE is pressed for time in many ways. We gave ourselves a year, and held ourselves to consistency because queer API content should be regular and devoted. We also adhere to a lunar chronology to disengage from Western heliocentric time. In aligning ourselves with the cycles of the moon, we refer both to a common pan-Asian tradition and infer our more marginalized interests: queer, introspective, embodied, femme—perhaps one can say ‘yin.’ You, too, have stayed consistent, with us. Thank you for continuing to show up—in print, in spirit, irl— again and again. Come out once more and celebrate…

IT’S A PARTY 🙂 *

When I first approached Connie, Andra, and Heidi about organizing an event together for FORTUNE’s final issue, I wasn’t sure where it was going to go. For a long time I was interested in organizing a showcase of Asian American artists who I felt were often unseen. At the same time, I was afraid that it would be niche, even for other Asian people. Often, I feel like events centered on Asian American identity are perceived as obsessively nerdy. If not, they are judged, often justifiably, as derivative of other minority experiences—specifically of black and brown people, re. Asian hip-hop. The lexicon of Asian references palatable to a non-white audience is limited to orientalist aesthetics or food. Qiapao and dumplings, boba and sushi.

The last two and a half years proposed a benchmark for Asian representation, mainly for East Asians. Crazy Rich Asians (2018) and the rise of- for better or worse- Constance Wu, Awkwafina, and Jia Tolentino; Yaeji and Rina Sawayama’s popularity; the critical successes of Korean films Okja (2017), Burning (2018), The Farewell (2019) and Parasite (2019), (the last winning four Oscars); KPop a la BTS slash BLACKPINK; the increase of Asian faces in fashion. Recently, HBO announced their first ever Indian-American reality TV show, Karma. A lot of this attention felt disingenuous and perfunctory, following the groundbreaking footsteps of brown and black activists. Media saying, “What’s next on the list?” Not all of these highlights were strictly Asian-American, but nobody’s counting.

So far, the biggest Asia-centric news in 2020 recycles the SARS crisis with a new coronavirus, proving the lasting vigor of yellow peril. Facebook informed me that this information has already dampened business in Chinatown. One of my teacher friends told me that her student’s parent wanted to withdraw her from class because of an Asian classmate. On the trolley the other day, I coughed and saw a couple of passengers changing seats away from me.

In May 2018, I had organized an event that had included Asian American performers—NK Badtz Maru, a Korean-American DJ from New York and Bamban, a performer of Filipino descent from Washington state. While I was excited about the lineup, it was poorly attended. Even though I knew it was probably because of the horrible weather, I was depressed by the turnout: does anyone care about this? Having grown up in the Los Angeles Valley, I was starting to realize how I had taken for granted the ubiquity of Asian communities around me. When I was younger, being Korean felt like a series of chores, mainly centered around attending church. The last thing I wanted to be was Korean. I wanted to be an individual, apart from my cultural baggage; myself, apart. Living in Philadelphia after college, I felt a constant subordination to the mostly white queer and creative institutions around me, sometimes even from other POC circles. It was like I was always substituting for someone who should be present: in an identity that is defined, in large part, in what being white and black is not.

Even the discourse between Asian Americans about Asian American identity is labyrinthian and tangled, with no real answers. Friction between too many nationalities and ethnicities packed into one label. Racism, colorism, fatphobia, ableism and queerphobia within our communities. Tension between ‘authentic’ practices immigrants and descendants safeguard and the separate realities in Asia proper. Modern Asian identity, when outside of laundromats and takeouts, seemed mostly defined by a very Western standard of class aspiration and political conservatism, crazy rich asians**.

When planning the event, Connie, Heidi, Andra and I reflected a lot on addressing the deep contradictions and racism in Asian-American representation and multiculturalism. The queer and femme slant of FORTUNE felt easy to represent, as most of our network were of queer and femme folk, and I already knew I wanted to showcase a spectrum of musical and performance styles. However, jigsawing together the rest of the lineup left me feeling guilty and queasy. In the year leading up to the event, I had encountered more Asian-Americans than I had in my 5 years living in Philadelphia, many of these connections through FORTUNE. I ate with members of hotpot!, a queer Asian and Pacific-Islander group, started meeting with a group of queer Koreans facilitated by musician Harim Jung, and attended the Philadelphia Asian Festival for the first time. I felt responsible for representing these and other’s experiences as fully as possible by casting a multifaceted lineup. However, I found the task of ‘curating diversity’ calculating. I was unconsciously earmarking each artist. Ana Roxanne, Diaspoura, Ani Malaya, Wo Chan, Raverbaba, Madam Data, and Agyn. East Asian, South Asian, Southeast Asian, Filipino, Indian, Chinese, Singaporean, Persian. What was I doing that was different from a Hollywood exec? I think sometimes, “Is it possible to build a unique, organic, and truly imaginative space for a Asian diasporic future? Would it only be possible through fragmentation?”

The night of the celebration, my emotions were in constant ebb and flow. The night was on the cusp of the Aquarius new moon, which fell on lunar new year’s day proper. A moon for purification, to begin the new zodiac cycle, ready to wax into light (what were my resolutions?)

Contentment lay in the center of my feelings, a knowledge that something special was happening, though what exactly, was unclear. Maybe it was just . Connie had brought a tree with light up leaves, which basked the room with a moonlit glow. The FORTUNE crew had brought to the Rotunda: samosas, onigiri, green tapioca dipped in milk. After Ani ended her performance, warm applause melted into bright chatter. Voices, in turn, faded into a stillness as Ana begin to sing. Bodies began to relax unto the floor, faces glowed red from the lanterns. Watching, listening, seeing what was being made.

Read:

* Text from event copy, written by FORTUNE.

** Anne Anlin Cheng’s insightful essay on Asian-American identity and representation