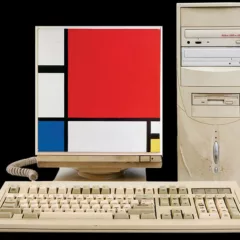

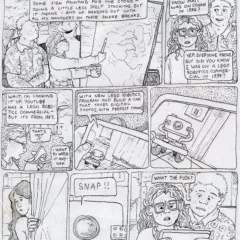

Like others of my generation, I loved playing with Legos as a kid. And the bright plastic building blocks are still popular with children today. My 10-year-old nephew is a huge fan. But with their various cross-promotional marketing campaigns – Batman, Star Wars, not to mention The Lego Movie franchise itself – and their increasingly specialized pieces, Legos are not what they used to be.

Legos today are less creative, less imaginative. That is, if the child only builds what the instructions tell them to build. When I was a kid, I’d initially follow the instructions and make the toy as pictured on the box. But that didn’t last long. Never satisfied with the directions, I always ended up making my own creations: buildings, cars, spaceships, etc. I inevitably began designing and building my own city, my own Legoland. My parents’ basement became the site of my urbis minima, or small city. I was a budding urban planner! But as with all good things, this came to an end when my father had me destroy my plastic metropolis after deciding I was too old to be playing with toys.

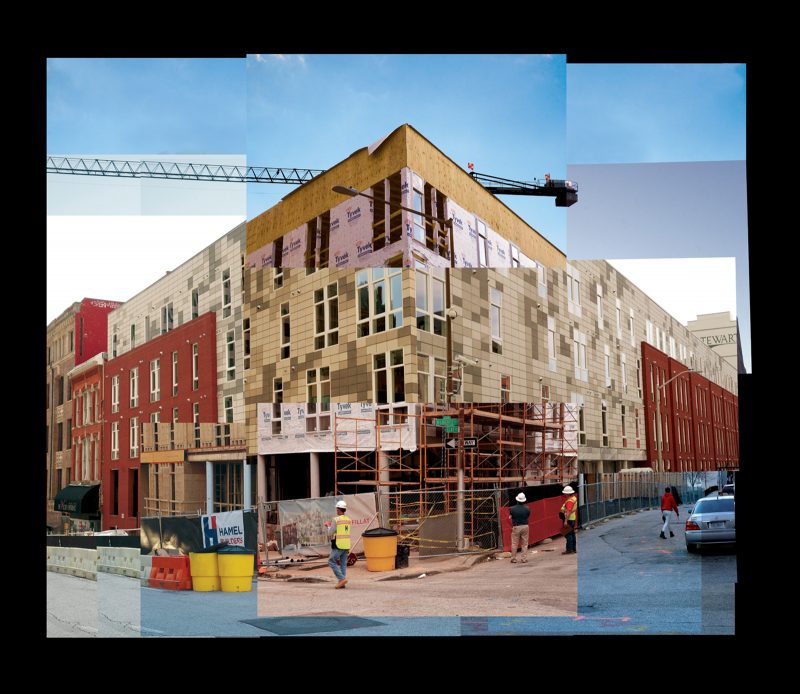

Never did I imagine I would one day inhabit a real-life city partly made of plastic. A few years back, I began noticing what I privately refer to as “Legoland Brutalism” cropping up around Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I used to live. Building after building went up appearing to be constructed of plastic Lego blocks. Like vinyl siding with fake wood grain, the exteriors of these buildings mimicked the look of their modernist predecessors albeit in an ersatz way. Perhaps this was to save on materials, plastic being cheaper than concrete. Or perhaps this was on purpose, as part of a new way of envisioning the city. Either way, it is slightly unsettling. If this trend continues, will we one day be completely surrounded by plastic buildings? Though that was the world I inhabited as a boy, I would never want to see it writ large.

While many people are familiar with Legos, not everybody knows what Brutalism is –even those who claim to! So let me outline a brief history of modern architecture here before moving on. In the late nineteenth century, after a long succession of revivalist styles (neoclassical, Gothic Revival, Egyptian Revival, etc.) and combinations thereof, a new vision of what architecture could be began to emerge. As with contemporaneous artists, architects during this era sought a new path forward in their profession. By the interwar period, this blossomed into what is now referred to as modernist architecture, loosely defined as minimalist, block-like buildings shorn of historical referents such as balustrades, columns, friezes, and ornamental detail.

There were two main exponents of this new vision: the Bauhaus school of Weimar Germany and the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier (a.k.a.: Corbu). Both the Bauhaus and Corbu sought to redefine architecture for the new century with a progressive vision. Tom Wolfe observes in his hilarious polemic, From Bauhaus to Our House, “worker housing” was the obsession of these left-leaning architects working in the so-called International Style. But what began as an ethos in the interwar period, devolved into a fashion after World War II. As the title of Nathan Glazer’s book, From a Cause to a Style: Modernist Architecture’s Encounter with the American City, suggests, what was once a deep ethical stance, became just as another architectural style.

Brutalism is simply a subset of modernist architecture that consciously moved away from the more elegant kind of minimalist designs of glass and steel being used for high-rise apartment buildings and corporate towers. Brutalist buildings are mostly made of concrete and have few if any windows. If you’re not familiar with the concept of Brutalism, you’ve probably seen examples of it in the backgrounds of popular science-fiction films. From Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) to Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 (2017), Brutalist architecture has served as the perfect backdrop for dystopian sci-fi movies. (When we were in our 20s, my younger brother and I often talked about making a science-fiction short film with Boston City Hall, a controversial example of Brutalist architecture designed by Kallmann McKinnell & Knowles in the 1960s, as the central motif. But this never came to be.)

Even if you don’t recognize Brutalism from the big screen, you’ve most likely set foot in one – many postwar courthouses, schools, post offices, and other public buildings were designed in this fashion. Washington, D.C. is awash with Brutalist buildings. Indeed, it is this style of architecture that President Trump is most likely referring to in the draft executive order informally titled, “Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again” (how Trumpian!), which was leaked to an architecture trade publication this past February.

Brutalism and Legos have a lot in common. They are both composite materials that are cast into repeatable forms or shapes for the purposes of constructing larger structures. Both have been around since the mid-20th century: Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation, the Ur-Brutalist building, was completed in France in 1952, a few years after Lego’s earliest version of interlocking bricks came out in 1949. And they’re both still here. Though it became less fashionable by the late 1970s and early ‘80s, Brutalism has seen a resurgence in recent years. There’s even a Facebook group called “The Brutalism Appreciation Society” (the stickler members of which I fear may have their qualms with this essay). Meanwhile, Legos have steadily increased in popularity over the last 70 years, overtaking Ferrari in February 2015 as “the world’s most powerful brand.”

But there’s an important distinction to make here: Brutalism is technically about material. The word itself comes from the French béton brut, translating to “raw concrete” in English, meaning the unfinished look of concrete after being cast. It was this raw, unfinished look that was favored by modernist architects. They actually had idealistic, positive associations with this “anti-aesthetic” as it was meant to suggest architecture stripped of its history, shorn of the calamities of the past. By strict definition, if we were to adhere to the “instructions” of architectural theory, Brutalist buildings must be composed of poured concrete, not plastic. However, the more popular understanding of the word “brutal” (as in harsh, inhuman, severe) often eclipses the technical definition. This populist understanding of Brutalism is what I’m referring to when I think of “Legoland Brutalism.”

It’s been several years since I first started noticing “Legoland Brutalism” in the Boston area. I now live in Baltimore, and see the same thing happening here. I suppose it’s fine in small doses. But if this trend of late-capitalist architecture catches on too much, we may find ourselves increasingly surrounded by these synthetic facades. I still love Legos. (Whenever I visit my sister’s place for the holidays back in Boston, I have to fight off my nephew to play with them.) And, since becoming an adult, I have gained an appreciation for architecture. I just hope that, moving forward, architects break free of the need to follow the instructions, and try to think outside of the box.

For Further Reading:

[1] “Brutalism” from Designing Buildings Wiki (3/9/2020)

[2] “Do You Recognise These Brutalist Buildings from the Big Screen?” from Phaidon.com (9/20/2018)

[3] “Trump’s Beautiful Proposal for Federal Architecture” in The Atlantic (2/20/2020)

[4] “Brutalists in LEGOLAND!” from Global Graphica (4/20/2018)

[5] “Brutalism: What Is It and Why Is It Making a Comeback?” in My Modern Met (12/4/2018):

[6] “The Brutalism Appreciation Society” on Facebook

[7] “Lego Overtakes Ferrari as the World’s Most Powerful Brand” in Brand Finance (2020)

Bio

Dereck Stafford Mangus is a visual artist and writer based in Baltimore. His artwork has been exhibited in galleries throughout Baltimore, and his writing has appeared in frieze magazine and Full Bleed, a journal of art and design published annually by the Maryland Institute College of Art.