Lounging naked on a tweed couch with oversized visor sunglasses and cuddling a fur coat, some might mistake the work of Polish artist Natalia LL’s (short for Natalia Lach-Lachowicz) Animal Art (1977) series for a modern-day Instagram post or Gucci advertisement. Working primarily in the realms of photography and film, her work presents an existential and intimate dialogue between “body and psyche” in which she presents herself as the subject. Described as radical, scandalous, and even pornographic, her notorious work continues to be the target of censorship, gaining momentum for feminist free speech in the art world. Throughout the six decades of Natalia’s career, one can infer parallels between the transitioning themes of the 83-year-old’s work to periods in her life: youthful defiance of gender roles and identity, spiritual recreations of the divine attributed to a mid-life near-death experience, to recent explorations of death.

I first learned of Natalia’s controversial art and personal life from her niece, who I befriended in 2014 during a study abroad in London. She spoke of familial conflicts between Natalia’s seemingly radical ideologies in conservative Polish society, her remote refuge in the mountains, rumored parties featuring bananas, and a shared love of cats. A recent viewing of The Medea Insurrection: Radical Women Artists Behind the Iron Curtain exhibition at the Wende Museum lent gravity to her work, among a cohort of Avant-guard artists from eastern Europe, during a period where extreme political repression discouraged free thought and individuality, especially from women.

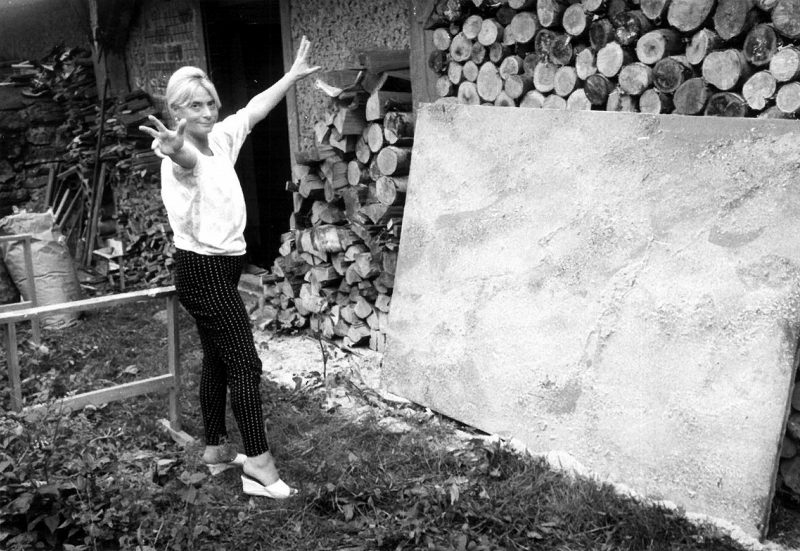

In her featured piece, State of Consciousness (1980), a series of black and white photographs capture Natalia draped in black, intently planted on a contrasting blanket of snow. Eyes closed and immune to the cold, she is lost in a dream state among the natural setting of the discreet mountainside. She goes on to hang from the branch of a nearby tree like dead weight. One leg poised she dances in the wind, contorting herself to become an extension of the tree as she swings — leading us to question whether the elusive performance is an extension of her consciousness or simply puerile playfulness.

Her accompanying essay of the performance still resonates in the context of our modern-day crisis. Questioning the relevance of existential necessities and materialism she writes:

In the world of hustle and bustle and buzzing activities I am proposing concentration. If the world, which came to existence without our participation, is to survive, we have to use the essence of the world. To activate energies that may enrich us through ourselves. The importance of the hurly-burly of mundane routines is short-lived. It is concentration that is the essence of our existence. Concentration on the idea and life. Being one with oneself.

Inspired by the current #wfh scenario induced by the COVID-19 pandemic (and admittedly struggling to maintain concentration in my work), I ask Natalia about her Owl Mountain house in the remote Polish village of Michałkowa. It was there she sought refuge from the political strife of Martial Law in Poland*, where she connected with herself, and not coincidently where she created most of her art. The loftiness of the house allowed her to make large-format works and host performances, or “seances” as she refers to them. She states, “the silence was also a help to fully focus on the work. I wasn’t distracted by anything from the outside world.” I take note.

She goes on to talk about the surrounding fields and mountains that became a backdrop for her work, such as State of Consciousness, and inspired her interests in Nordic mythology: “I made a lot of my works with conceptual characters but also mystic ones, connected with myself…I was becoming The Witch (1993), Brunhild** (1994) or Odin’s Raven (2010).”

Using nothing more than a camera, her body, and occasionally familiar household items as props, Natalia unapologetically exposed herself through a composed manifestation of her thoughts. In scenes such as Odin’s Raven where she straddles a ribbed yoga ball wearing dark sunglasses, a feather headdress and studded open-toe sandals, her mystical role play can be easily written off as parodic, a clever Halloween selfie. Yet to understand her work is to appreciate the unbound freedom that persists. Set in equivocal scenes of fantasy, she positions herself in roles of power freed from the stigmas of convention, particularly gender identity.

“Art is a very important part of my life and always has been. It’s an inseparable element. I believe that art influences reality because it’s a part of my mind and my thoughts. It’s a part of me.”

As someone who has been hailed as a pioneer of feminist art, I couldn’t help but ask Natalia, what it means to be defiant and if that definition carries the same meaning in modern day context. She notes, “The times are still changing, the world is going on and the definition of ‘defiance’ is changing also. It is always a fight for freedom and possibility to be yourself, to express yourself in a way you want…”

In a moment in history where we cling to the virtual world in desperation for social connectivity, feel pressure to conform to societal standards, and are interrupted by never-ending distractions, Natalia’s work reminds us there is much to be harnessed from our time in isolation. She teaches us the art of introspection.

This weekend, I disabled wifi and sat in the backyard as I wrote this article. Perhaps we take a moment to embrace this “great pause” for what it could come to be.

“The times pass by but the art is still.” – Natalia LL, 4/8/2020

The ZW Foundation was recently established to preserve the work of Natalia LL @natalialachlachowicz and to provide a field for open discussion on contemporary art and science. Follow their work @zwfound

For information on Natalia LL’s work as part of the group exhibition, The Medea Insurrection: Radical Women Artists Behind the Iron Curtain exhibition, check out the Wende Museum website at https://www.wendemuseum.org

*From wikipedia, “the period between 13 December 1981 and 22 July 1983, when the authoritarian communist government of the Polish People’s Republic drastically restricted normal life by introducing martial law and a military junta in an attempt to throttle political opposition, in particular the Solidarity Movement.”

**From wikipedia, a powerful female figure from Germanic heroic legend.