At such a tumultuous and frankly traumatic moment in our history, it almost feels frivolous to look at art. I personally have been struggling to understand what place can art possibly hold in my life when I must constantly bear witness to the destruction brought on by the coronavirus pandemic and everyday instances of police brutality which have disproportionately affected African American communities.

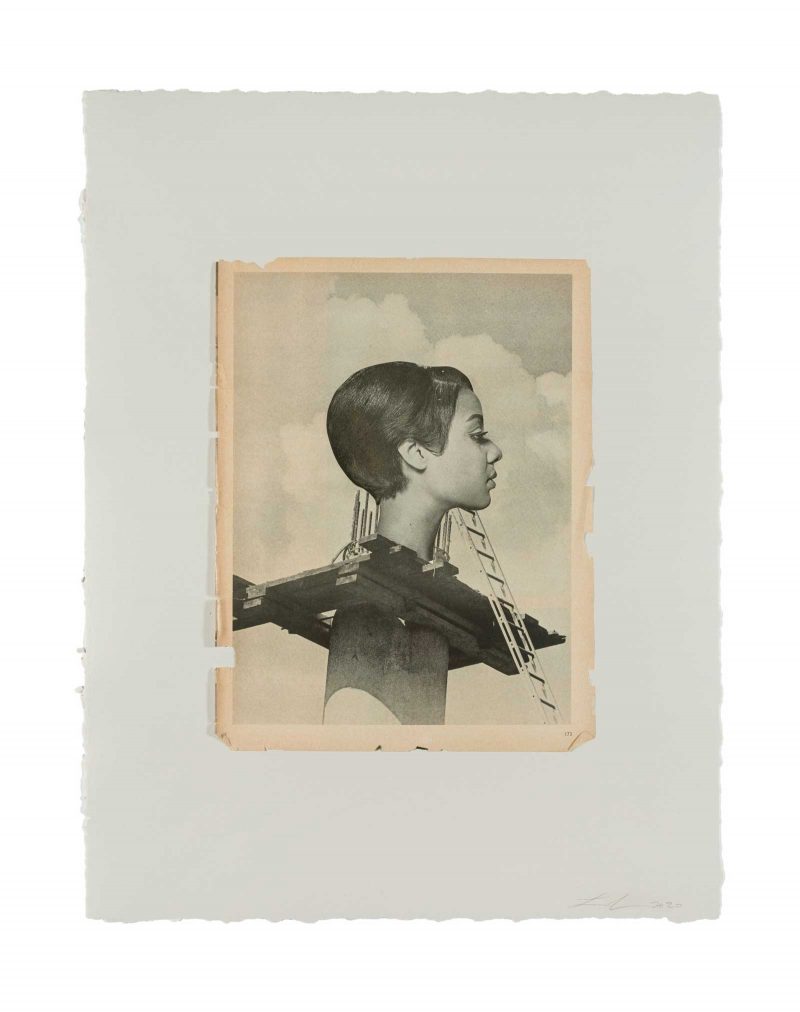

Lorna Simpson’s recent online exhibition, “Give Me Some Moments,” at Hauser and Wirth is a timely response to questions about art’s usefulness in these dire times. In this venue, art does not serve a palliative function. Rather, the featured collages, many of which were created at the beginning of the lockdown, work together to urgently communicate how it feels to be Black in this moment. Simpson fashioned these collages with photographs of the elegant Black men and women who graced the pages of Ebony and Jet Magazines in the 1960s and 70s. Through her abrupt interventions, Simpson creates works which serve as apt metaphors for the conditions of Black life in the United States, particularly as they relate to W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness. To emphasize this point, Simpson remarks in the exhibition’s accompanying text, “We’re fragmented not only in terms of how society regulates our bodies but in the way we think about ourselves.”

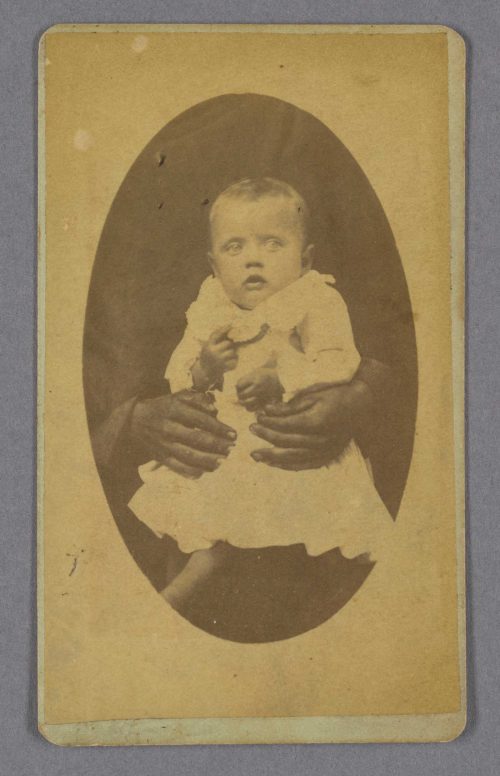

In addition to engaging with contemporary notions of Blackness, Simpson’s works are a powerful intervention into the archive, which has imposed its own violent form of fragmentation on Black people and our bodies. Simpson’s quote brought to mind another online exhibit which opened last year at Emory University’s Rose Library titled, “Framing Shadows: Portraits of Nannies from the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection.” The exhibit features a series of late nineteenth and early twentieth century photographs of Black caretakers, often women, with their white charges. One portrait in particular bears an eerie resonance with Simpson’s musing on Black people and their relationship to fragmentation.

Visible in the photo is a white baby being held by a pair of Black hands. The photographer, likely at the direction of the family commissioning the portrait, intentionally cropped the portrait to obscure as much of the caretaker’s body as possible. While this image bears the most obvious similarities to Simpson’s physically disembodied subjects, all of the portraits embody the psychological fragmentation with which Black people must understand their place in the world. As the didactic text in the Emory exhibit asks viewers, how did these unnamed African American women, who spent so much time away from their own families, reconcile the need to bond with the white children while being told that these children were superior to them? Such lived reality likely required, as Simpson suggests, a fragmentation in the way these women thought of and carried themselves in order to survive.

It is important to consider these two exhibits, one historical and one contemporary, in tandem with one another because while commentators do not hesitate to call these “unprecedented times,” there is a danger in thinking of this moment as anything but the product of a long history of erasure and dehumanization of Black people. Understanding this violence through the lens of the archive keeps us moored to this history. Simpson, through her masterful manipulation of archival materials, prompts us to look at photographs in a different way. By stripping away the artifice of these commercial images, the artist subverts the archive’s suppression of Black interiority and humanity. In doing so, she invites us to take a critical look at the photographs in her exhibit, and those which inhabit more traditional institutional archives. Simpson encourages a necessary meditation on Black lives at a time when the botched governmental response to the pandemic and systemic police violence work to render us invisible.