A Moment’s Pleasure, a new installation by contemporary Black artist Mickalene Thomas at The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), opened last November, a few months before the coronavirus made the world stand still. It would have thus been impossible for the artist to predict how such a global cataclysm could alter the meaning of her work. Of course, this is true of so many aspects of the world right now, not just in the art world. Modern civilization as a whole is undergoing a fundamental reevaluation of its economic, institutional, and political values. Many institutions have closed their doors, perhaps forever. Yet, reinterpretation is at the heart of A Moment’s Pleasure, both as part of Thomas’ original vision and in the context of Covid-19.

It’s a shame that the virus shut down the museum so soon after the opening of Thomas’ installation. After the abrupt closure, the title almost seemed like a bad joke. Then again, the coronavirus has added new meanings to the work when considering the full timescale of A Moment’s Pleasure, not just the space it fills. A complete timeline would begin in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Thomas was growing up in Camden, New Jersey, a city not unlike Baltimore. That was when her sense of aesthetics was first informed by her parents’ tastes: the bright colors and funky fashions of the disco era. At this time, the east wing of The BMA had not yet been built. Four decades later, Thomas was selected as the first in a biannual cycle of artists to reinterpret the lobby area of the museum’s east wing, which was completed in 1982 and remodeled in 2014. Four months after it opened in November 2019, A Moment’s Pleasure closed due to Covid-19. For the past six months, museum staff and workers the world over became reacquainted with their domestic spaces as they worked from home. Meanwhile, the museum remained shuttered, its collections unviewed aside from guards on their rounds.

Making people feel at home

Thomas’ mixed-media installation radically alters the east wing lobby of The BMA, transforming it into a sort of avant-garde domestic space. Museum Director Christopher Bedford likes to call it, “A living room for Baltimore.” And this is exactly how it felt before the virus disrupted everything. A lobby isn’t normally thought of as a living room. But in many ways that is what a museum lobby is: it’s a place to hang out or meet up before venturing on to other places. The east lobby of The BMA is the main public gathering area of the museum, connecting the auditorium, gift shop, restaurant and restrooms, as well as entry points to the galleries. Visitors not planning to enter the museum proper – say to browse the gift shop or hear a concert or lecture in the auditorium – have to pass through this space to do so. In this sense, they become unwitting performers within the mise en scène of A Moment’s Pleasure, blurring the line between art and life. It truly is a living room.

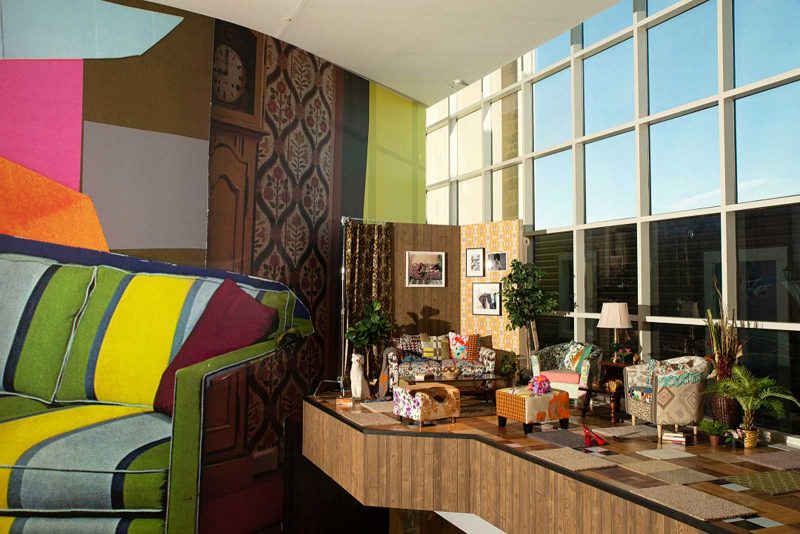

Drawing upon interior decoration motifs from African American homes in the 1970s and ‘80s, Thomas’ massive installation reconfigures the arid modernist space of the museum’s east lobby into a colorful, lively, and cozy meeting place: with vintage linoleum floor tiles, faux fur-covered benches, and a two-story high wall mural depicting a giant collaged couch, Thomas makes you feel at home in a part of the museum that normally feels like an airport check-in area. There is also an actual living room set up in the corner of a second floor overhang, complete with a real-life couch, coffee table, and framed photographs by the artist hanging on a makeshift wall. Stacks of books by famous Black authors punctuate this diorama.

Beyond her interior interventions, Thomas further altered the museum’s façade directly outside the east lobby and on an outdoor second-floor balcony. With a bit of stagecraft, the east wing exterior of The BMA now appears as a series of Baltimore rowhouses, the illusion of which is enhanced with actual marble stoops (so iconic of Charm City) that jut out from the large-scale architectural photo-illustrations. Even when just walking past the museum, the effect inspires a double take. After the brutal murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd by police earlier this year, two giant black-and-white banners reading, “Can we breathe” and “Black Lives Matter,” were hung in front of the faux façades. This addition further blurs the line between art and the larger world in that it declares the political position of the artist and museum while also reflecting those same sentiments of Baltimore residents and business owners: many buildings across Charm City now have similar signs placed in their windows or hung across storefronts.

The third and perhaps most intimate space of A Moment’s Pleasure — and the only one the public is invited to interact with directly — was built around a large shipping container lowered onto the exterior balcony of the museum. (It sits right behind the second stories of the faux rowhouses.) The steel box was covered with vinyl siding, trim, and mock windows. A functional doorway was cut into its center so that the whole structure appears as an oblong house facing the windows above the east lobby. You enter this “home” by briefly stepping outside onto the balcony, walking up a wooden deck-like ramp, and letting yourself into this special space on the previously unused east wing balcony. Once inside, you find a continuation of the vintage aesthetics found in the lobby: fake wood paneling covers the walls; shag carpet spreads across the floor; and reupholstered chairs with funky patterns invite you to take a seat and chill out. There’s even a mini bar stocked with ‘70s-style glasses. The space is divided into two rooms, with the bar (from which drinks are actually served during special events) and a screening room where different videos are projected on a loop. Paintings, prints, and drawings by local artists like Zoë Charlton and Theresa Chromati hang on the walls, and the videos are also by Baltimore-based creators such as Erick Antonio Benitez, Clifford Owens, and local music legend TT the Artist, whose “Gimme Yo Love” gets people of all ages bouncing to her joyful beats each time it comes around in the rotation.

The overall effect of A Moment’s Pleasure is to make visitors to The BMA, especially those who came of age in the 1970s and ‘80s (like Thomas did), feel at home in a museum environment, which can all too often feel cold and sterile. After opening last November, there were only about four months for visitors to experience the massive overhaul of the museum’s east lobby and east wing exterior before The BMA closed to the public due to the pandemic. When the museum reopens later this month, while standing or waiting in A Moment’s Pleasure, visitors will likely reflect on their own domestic spaces where they have been spending so much time this year.

Final and Future Thoughts

The BMA is scheduled to reopen in phases later this month. What will this look like? Who will return and in what numbers? Is the world ready to engage with art again? Is art essential? Which artworks will resonate most? How might a work like A Moment’s Pleasure be reinterpreted after such a calamity? It may be a while before the cargo box part of the installation reopens, as it is a fairly confined space. But you will be able to access the east lobby on September 16. The remodeled exterior is always on view, at least until next spring when A Moment’s Pleasure comes down.

Those first four months constituted a far shorter moment of pleasure than was originally planned. But the installation is scheduled to be on view through May 2, 2021. With her latest and most ambitious project yet, Mickalene Thomas completely transformed the most public part of The BMA. The coronavirus then altered the meaning of that intervention. With what will be in effect her second opening this fall, let us hope more people get to experience A Moment’s Pleasure.

Mickalene Thomas, ‘A Moment’s Pleasure‘ at The Baltimore Museum of Art through May 2, 2021.