Author’s Preface: SYNESTHESIA describes the ability to sense and feel multiple senses as one– sounds become colors and colors become smells. With that, SYNESTHESIA is also a new series by Alex Smith, exploring the sounds, collaborations and imagery of the visionary artwork from culturally impactful Philadelphia albums. We’ll be exploring the ideas, story and vision behind iconic and soon-to-be iconic album covers from some of Philly’s best musicians and the artists they work with.

The opening notes on Philadelphia punk band Pinkwash’s 2016 debut album COLLECTIVE SIGH (Don Giovanni Records) are– well, for one they’re not exactly notes. The sound you hear is a primal siren, a violent distorted bleaching wail that sets up brilliantly the ensuing chaos. COLLECTIVE SIGH is white noise, blown out and in-the-red from the semi-melodic nuclear guitar drone of Joey Doubek, all propelled by a hair trigger precision drumbeat from Ashley Arnwine. Despite their bandcamp’s claim of being “false punk”, Pinkwash is formidable; if this is the false punk, the real stuff must have the ability to melt tanks.

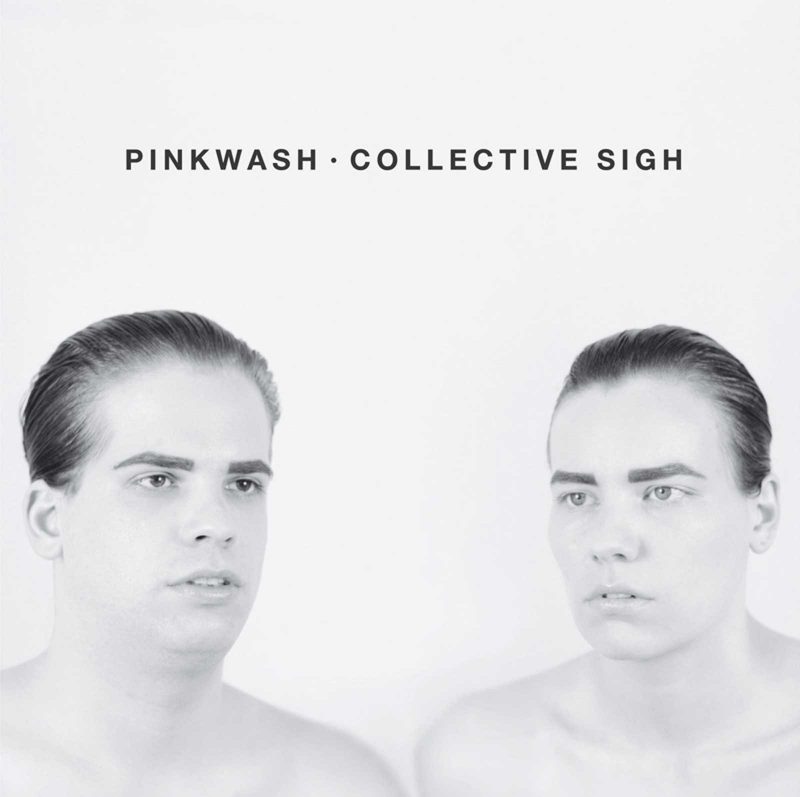

The image encasing this noise shows our protagonists’ two faces– angelic, cold stares on a pristine, graying background that melts into their skin as the two gaze blankly into an unknown horizon. There’s a stark look of disappointment on their faces, but it’s one of resignation– the band is indeed taking a collective sigh, not as a prelude to defeat but as a call to charge on. The photo of the band is from the thoughtful mind of artist Amy June, whose work extends to textiles, ceramics, and woodworking.

Amy June on the album cover – rooted in friendship and attention to process

“Joey had the idea for the general concept/design and it just was a given that Amy should shoot it,” Arnwine says about the decision to use June for the album cover.

It felt pretty organic and I remember feeling proud to have her work on my band’s record cover as if it rounded out the project as a whole. Besides the fact that Amy’s dedication and appreciation for process- as well as the final end product- is apparent to anyone who works on a project with her (or looks at her photos or plays a show that she booked), Joey and I are also both from the D.C. metro area and so is Amy. We had mutual friends, including Joey who did know her prior to moving here, and including our close friends who run the label Sister Polygon and during that time Amy would often travel with Pinkwash to shows in D.C. to meet up with our larger friend circle there and beyond. We were all just pretty close friends at that time and this felt like an extra added layer of intentionality and connection, which was awesome.

The result is a stunning piece of punk photography, a work of art as curated and in the moment for this generation as Martha Cooper or Rick Flores, (or dare I say it, Glen Friedman) were for the scratchier, more nihilistic ‘80s punk forebears.

Photography – bold, black and white and imperfect

Growing up with DC punk, being a suburban straight edge, mixed kid with city dreams, that type of photography was so important to me,” Amy reflects.

So, thank you for bringing up the work of these other folks and thank you for relating my work to theirs! It was definitely what I was trying to replicate in my high school darkroom, with flash and shooting from the hip and printing with the negative edges in the frame. Always bold, black and white, and imperfect. My senior year of high school I went to Govinda Gallery in Georgetown, D.C. to see a show of images from Punk Love (iconic Susie J Horgan images from the rise of punk in D.C. in the early 80’s) and it changed my life. I knew then that was what I wanted to do: tour, travel, mosh, flip off cops, make tons of energetic images and just enough money for your next coffee and gas to the next gig.

This would fuel June’s journey towards a relationship with impactful images and how those images can capture the essence of punk and underground music. Eventually June would find her way to an internship with Govinda, though she was not off and running yet– her experience there was beset with extreme sexual harrasment, “but I felt at home with my hands on these big darkroom prints of kids scissor-kicking off of amps into the crowd below,” she insures.

It’s her spirit and fierce connection to community that informs June’s work. At her artist site, you can find wistful images of punk rockers in their more natural habitats– rusting pick up trucks, barefoot in shallow ponds on beatific spring days; there are also fantastic, empowering shots of locals from her trips to El Salvador and Mexico, the subjects in hard focus, emanating color and vibrancy. Even the black and white photography here captures this brightness, a far cry from the dull umbras Hollywood would have us believe coats the landscape south of the US border. On her trip, June relates:

Amy June goes south of the border, shoots vibrant color photos

I was taken aback by the vibrancy of seemingly every single thing. I didn’t choose my subjects so much as happened upon these spaces as they were, walking through CDMX and small villages outside the city where there are generations of families fighting for a living making traditional craft work for tourists. It really mirrors what you see on the borders of reservations here, in the northern plains and southwest. I am certainly guilty of bringing my own Western gaze to these spaces, not speaking Spanish and taking images without being able to fully request consent. If I were to travel to Latin America again, it would be with better language skills, first and foremost. But, that aside, this was during a time when I was really trying to flex how to use color film to my advantage and Mexico’s palette did not disappoint. Even night time images of food carts are rich with reds and yellows. The blue of the sky, the burnt sienna of terra cotta roof shingles, that deep blue of Frida’s Casa Azul, the elaborately decorated graves and churches. I wasn’t choosing the colors so much as there was no other option but to celebrate them.

Equally as important to June as representing the natural beauty and essences of her subjects is navigating the world as a queer punk rocker, an artist, but also as an Indigenous person who feels the weight and influence of the western world. This has afforded her a chance to bring what the “stare-and-gawk” academic art world would call artisan works into her craft, particularly with her project Holamooki. June says:

Holamooki project by Amy June explores queerness and indigeneity

My most recent project, Holamooki, is an exploration of all the ways to look, be, feel and practice the intersections of queerness and modern Indigeneity. Of course people do not equate functional work, or even photography a lot of the time, to art. This argument is as old as time: those who make functional work are just “crafters,” and photographers are documentarians rather than artists. I gave up on trying to buy into the Art World many, many years ago, realizing myself and my work would never be taken seriously, as a punk, as a homo, as a mixed Native person– you’re always “too much” or “not enough.” The only way for me to get into galleries and gain representation is to exploit my identity to a straight, white gaze, and I simply have never been able to do that. What I create, money I may make, and what I learn is always meant to be disseminated back into my community and I hope to hold to that standard forever rather than deny my blue-collar existence and try to climb up into the Art World and Industry.

What is Pinkwashing?

Which brings us to Pinkwash– a band who has spent their own orthodoxy and exchanged it for challenging noise-rock music that rails at the horrifying spectre of the medical industry. “Pinkwashing” is the idea of using disease, particularly breast cancer, to sell products or to sell the consumer on the idea of charity within an industry that looks to exploit. The band feels personally impacted by these consumerist notions in the medical field and songs like “Cancer Money” and “Your Cure” speak directly to that. The cover of COLLECTIVE SIGH, then, looks to paint the band as both the solemn medical professional shrouded in whites and grays, blending in seamlessly into the cold background of a hospital, and this industry’s victim.

Amy and Ashley talk about the Pinkwash cover, a staged photo versus street photo

Arnwine remembers of the shoot:

The shoot was done in Amy’s bedroom at the time at 49th and Walnut. I was stressed because I was in charge of getting white sheets to hang up as a backdrop for the shoot but I was running super late and had waited until the last minute. I did eventually make it there with some sheets and tools to try and hang them to the walls and we rigged something up eventually I guess, because we did get some good photos out of it. Joey and I had to basically lean extremely close together and we were kneeling on our knees and eventually it got pretty uncomfortable and sweaty and hot but we kept our composure! Once the shooting actually started happening it was a lot of testing and trying out different lighting and angles and poses etc. All in all it was a total success though and I remember feeling pretty happy with the final result and I trusted Amy as well. Joey and I both know her to have good taste and an appreciation for both the process and end result, it’s just how she relates to art and the execution of anything creative she is working on in general.

June recounts:

That shoot was very out of the norm for me…Though I was privileged to study analog photography in college, I never got into using backdrops, studio lights, and other kinds of manufactured ways of creating images. It has always presented extra hurdles, extra ways to miscalculate your lighting and how things will appear on film, and the added pomp and circumstance of backdrop stands, lights, umbrellas and so on, at least for how I shoot, has always seemed to make the subject less comfortable in front of my lens. I used to exclusively shoot large format (4×5) and in this digital age, putting someone in front of a large camera with bellows while you, the photographer, are hidden behind a dark cloth or have your face shoved into the ground glass viewing box can make it harder to connect with who you’re shooting

This process could not have been more removed from shooting a subject on the street, in available lighting, with the opportunity to move and change and re-frame and so on, at will. Perhaps it is because I’ve always felt like a less than technical photographer. [I’m just as] interested in messing up, the outtakes, the b-sides, the experience of moving and being with your subject through space and sometimes time. I’ll always prefer the last minute, no-direction shoots even if it means a lot of reshooting!

It’s a process that works. Both Doubeck and Arnwine are on display for a public to accept or reject, to feel and see and experience their skin as a part of the artistic dynamic of the music. “I would be lying if I said I liked seeing my face everytime I looked at our album cover!,” Doubek says. “Even though sometimes I feel self conscious setting up my weird vogue merchandise at the metal show, it’s precisely the reason why I wanted to have an image like this. Punk bands aren’t on their own album covers anymore!”

It seems that if there are images of punks on their album covers, they’re not casted in a way that captures both the seraphic and the dour. Moments on COLLECTIVE SIGH soar (the midway point of “METASTATIC”), others wedge their way into darker, more unexplored realms of your consciousness (the unhinged dark faux metal tribal drone of “BREVITY IS UNKIND”). What better way to capture this dream of a sound than with the stark, vulnerable visages of two of Philly’s most exploratory, yet grounded musicians, by one of the town’s most promising artists. What a better way to celebrate COLLECTIVE SIGH.

You can purchase “COLLECTIVE SIGH” by PINKWASH on their bandcamp. Stream PINKWASH on Spotify or Apple Music.