I once sat for Gilbert Lewis, the esteemed Philadelphia figurative painter whose oeuvre is the subject of four shows this Fall in Philadelphia. I am one of the many male models, probably hundreds, that modeled for the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art (PAFA) alumnus and teacher over his prolific career spanning four decades.

Wandering through two in-person shows at the Kapp Kapp Gallery and the Woodmere Museum, and one virtual show at the William Way website was a compelling exercise in recollection. (While all four Gilbert Lewis shows were originally scheduled to run concurrently, the PAFA show has unfortunately been delayed due to the pandemic and is scheduled to open November 19.)

I was not a passive observer of Lewis’s works but shared a common experience with these sitters. I had sat on the same chair as they had in Lewis’ studio twenty years ago. Although details such as who connected me with Lewis and how many sittings were required, elude me now, I strongly remember a sense of empathy from the painter, an atmosphere of coziness and the warmth of the studio lamp in the evening glistening on the dark wooden floor.

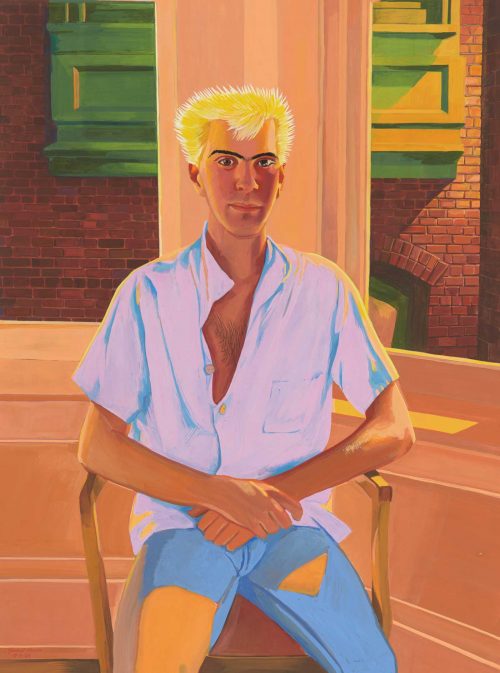

A palpable tenderness, awkward at times, to reuse the title of the William Way show, permeates Lewis’ portraits of young men or elderly folks and even his still-lifes. Take the large “Untitled Technicolor Portrait” (Kapp Kapp) of a young man with spiky bleached hair, or of an older female wearing a floral-patterned blouse “Untitled August 30, 1982” (Woodmere), a resident of a nursing home where Lewis worked for a while. They both exhibit quietude; the gaze is soft; the lips are gently closed. Both characters could have easily been rendered differently. The torn jeans, unbuttoned shirts revealing a patch of dark chest hair for the young man could have lent an irreverent or sardonic tone. Likewise, for the colorful busy print of the elderly lady’s clothing combined with her ostentatious brooches and gold-hearts necklace, her heavy upper eye lids and dark circles under the eyes. Au contraire, they exhibit no disdain and no tension, of the kind that pervades David Hockney’s portraits for instance. (Incidentally, Lewis greatly admired Hockney.) Instead these portraits reveal a profound humanity. They are non-judgmental.

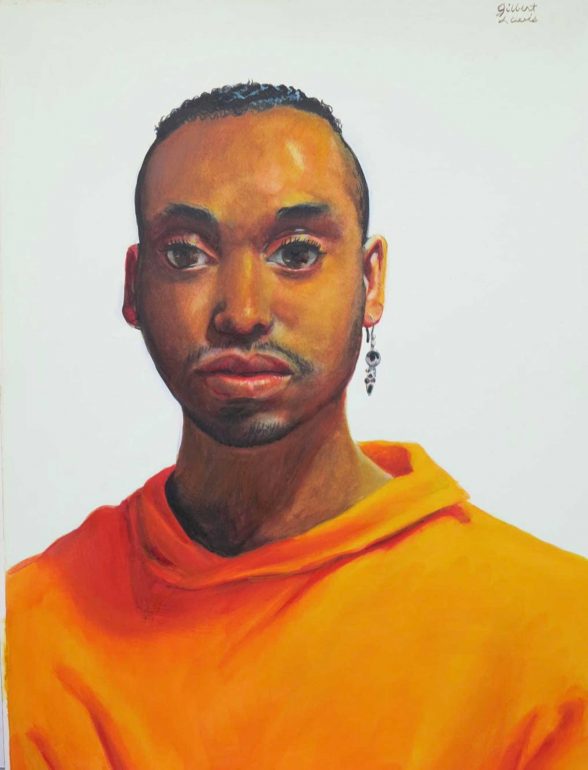

In fact, Lewis’s models have uniformly confirmed, and I am adding my voice to their chorus, that the artist was genuinely interested in what they had to say during sittings. He let them wear the clothing of their choice, sometimes let them bring their own music and asked questions about their lives. Many sitters felt at ease and opened up. Lewis came to understand how privileged and intimate these moments were. This excerpt from a quote by Lewis, aptly on display on a wall at the Woodmere, undoubtedly reveals the artist’s deep-rooted compassion for two distinct vulnerable groups: “One of my motivations in painting has been to celebrate the beginning of adulthood for the young and the final period of life for the old… What struck me is that both young men and the old are ignored by society”.

While he was immersed in the young male gay world, the bonds that Lewis forged as an art therapist with the residents of the nursing home, where he worked for many years, gave the artist invaluable insight and depth of understanding into these peoples’ lives. The painter was not only a faithful observer but a trusted listener.

But perhaps it is Lewis’s still-lifes that best encapsulate the frailty of human life. They are utterly simple, delicate and beautiful memento mori. In “Still Life with Tulip” a faded bright yellow red tulip is set in a simple vase, and the bent stem next to it extending beyond the picture frame implies a flower in an equal state of wilting. In another vase next to the one with the tulip, a single rose leaf on a flowerless stem is coupled with hardier green foliage. They are sustained by little water. Both vases are symbolic reminders of the brevity of life. As the scholar Christopher Reed and author of Art and Homosexuality expressed it in a recent talk, Lewis’s flower still-lifes stand comparison with other well-known 20th century gay artists who used flower still-lifes to convey sexuality “symbolically or in juxtaposition”. Robert Mapplethorpe comes immediately to mind. I was not familiar with Lewis’s still-lifes until these shows. They were a delightful surprise and I wished more of them were on display.

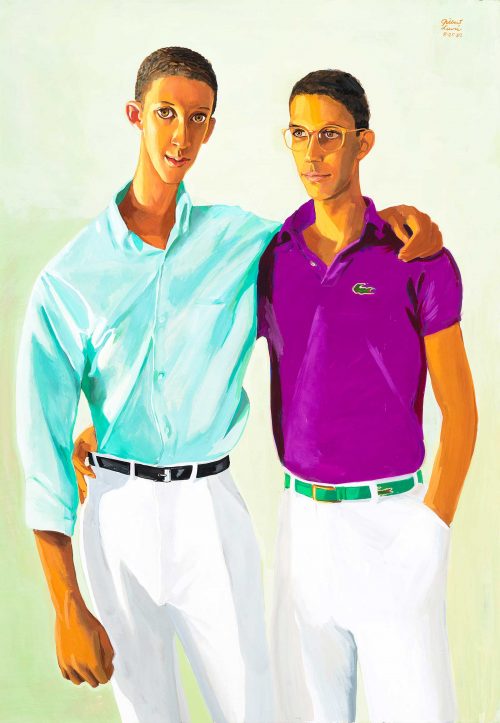

Vulnerability and fragility are omnipresent in Lewis’ portraits. The sitters’ expressions are never defiant. The poses don’t exude overt confidence. Even the contrasting perspectives, in particular in the nude paintings, “Untitled (Young Man Reclining on a Covered Chair)” (William Way) or “Untitled” (Courtesy of John Wind, Woodmere), highlight this sense of fragility through physical instability. The young gay men that Lewis affectionately depicts are no doubt out of the closet. At the same time, they display a certain restraint, perhaps inherent to the coming out process and the self-imposed societal conformity of the 80s and 90s. Their gayness is not cried out loud as in the sulfurous and eroticized male portraits of Paul Cadmus. But it doesn’t make Lewis’ portraits of young gay men less avant-garde. The subtle and sweet evocation of couplehood displayed in “Untitled August 25, 1983” (Woodmere) where one young man tucks a finger in his partner’s waistband, behind his back while the partner puts his arm around his shoulders shows a kind normalcy and casual acceptance rare for the period.

Lewis’ activism is not in your face. It is no picketing activism of the like of Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings and others pioneer gay liberation demonstrators who marched from 1965 through 1968 in front of Independence Hall when Lewis was an art student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Instead it is quiet but nonetheless relentless in its breadth and longevity. His benevolent gay male gaze has fallen over two generations of Philadelphia gay history.

Equally important and profoundly intertwined with its subject matter is Lewis’ masterful technique. His gouache expertise is rooted in his academic training and his deep appreciation of classical masters in particular Italian Renaissance painters’ painterly technique. The vivid strokes of the combed hair in “Untitled (Blonde Portrait)” (Kapp Kapp) or those capturing the texture of velour pants in “Untitled Male Portrait (Cable Knit)” (William Way) are delightful details attesting to Lewis’ perfect mastery and at times, playfulness with the medium. Another source of delight is Lewis’s color palette. He is an unabashed colorist. The solid colors of the men’s fashion of the 80s provided a limitless source of material to the painter. Often set against a luminous background these colors are exhilarating and offer a remarkable contrast to the quiet demeanor and gentle pose of the sitters.

In conclusion it is important to acknowledge the timing of this unique concerted homage between these four local venues at a time when the artist himself is a position of frailty and vulnerability, incapacitated by illness requiring constant care and monitoring by his close friends. Thanks to the dedication of Lewis’ friends, former colleagues, curators, gallerists, who judiciously thought that the moment was ripe, the public can start to grasp the scope of Lewis’ work, its uniqueness and understated contribution. I look forward to the PAFA show, which will highlight Lewis’ relationship with one particular model Tony and the specific body of work which came out of it.

Woodmere Art Museum “Gilbert Lewis: Many Faces, Many Figures” July 25 – October 25, 2020

Kapp Kapp Gallery “Gilbert Lewis: The Mind of a Man 1982 – 2009” September 18 – October 24, 2020

William Way LGBT Community Center “Gilbert Lewis: Awkward Tenderness” (Virtual show)

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts “Only Tony: Portraits of Gilbert Lewis” November 19, 2020 – May 16, 2021

Bio

Patrick Coué is interested in the intersection of art, culture and travel. An avid Philadelphian he is combining his background as an art history instructor and culinarian tour guiding locally and customizing trips to France and other delectable destinations at VoyageActually.com