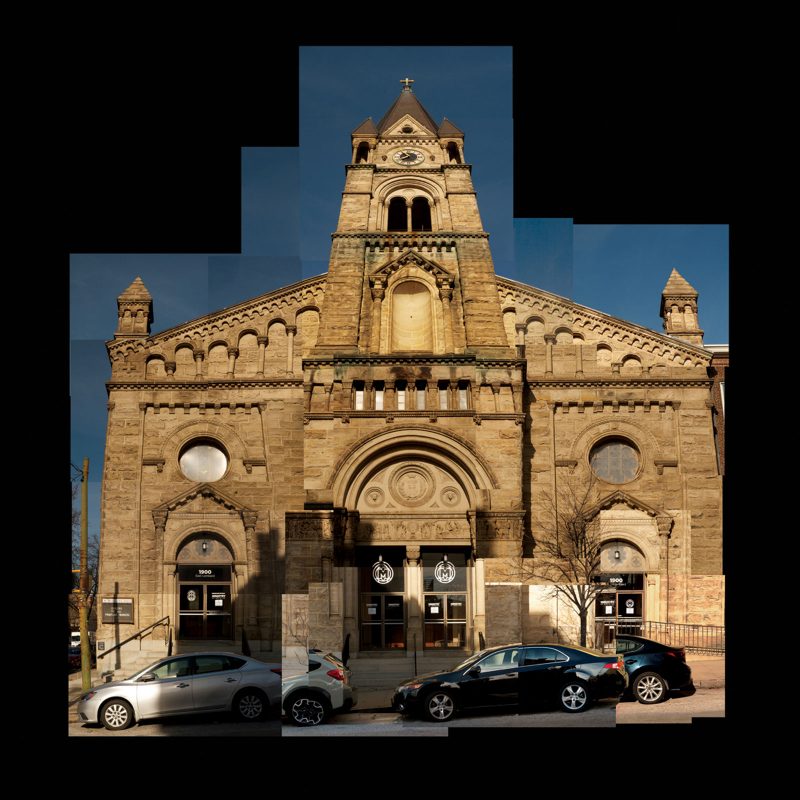

Earlier this year, before Covid-19 caused public building closures around the world, my partner and I found ourselves in two different churches for reasons other than worship. First, for my birthday in early February, some of our friends invited us out for drinks at a church building that was converted into a brewery last year. Located in the Upper Fells Point neighborhood of Baltimore, Ministry of Brewing inhabits the former St. Michael’s Church, an early Romanesque Revival structure built in 1857, abandoned since 2011. According to the National Register of Historic Places, St. Michael’s served the “significant waves of German Catholic immigrants that settled in East Baltimore during the mid-19th century and the Redemptorists who took charge of these German Catholics as part of their mission here in Baltimore.”

Photomontage by Dereck Stafford Mangus, 2020.

Many of the interior details of the high, barrel-vaulted ceiling at St. Michael’s remain intact. But much else has changed: the pews have been replaced with long wooden tables and benches; a 40-foot long bar with crushed oyster shell concrete extends along the right side; and most of the typical church accoutrements have been either replaced or updated to accommodate the building’s new purpose. Most surprising of all was the shiny new brewing equipment standing tall with modern triumph where the altar used to be. This former house of God had been converted into a temple for Bacchus. But was this sacrilege? Maybe not. After all, congregants used to take communion at this exact spot. The family-friendly brewery was crowded that day and everybody seemed to be having a good time, at least more so than I ever saw when going to church as a child. Still though, I couldn’t help but wonder, “What would Jesus think?”

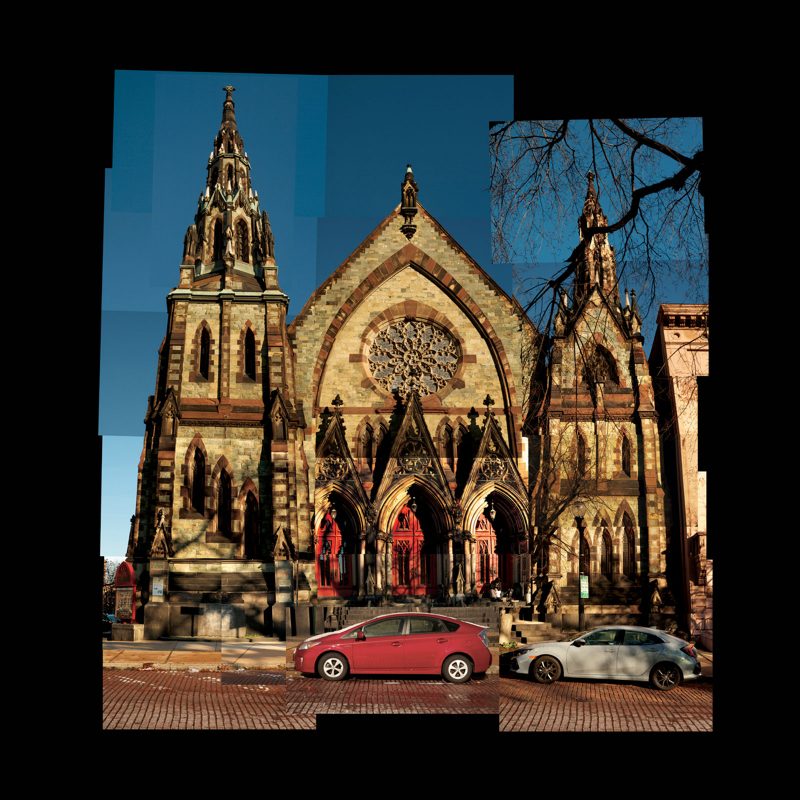

A month later, we went to see the Baltimore band Wye Oak perform at St. John’s United Methodist Church in Charles Village. Unlike St. Michael’s, St. John’s is still a functioning church with “inclusive and informal” worship services every Sunday morning at 10:30 (currently via Zoom). Before the pandemic hit, the church rented out its various spaces during the week for community groups and special events. When we were there, the pews had been removed to make room for the show, which was sold out so we were packed in like sardines. A church is actually a really cool place to have a rock concert. The acoustics are perfect, and the interior aesthetics provide an intimate setting. In fact, just the other week on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, Fleet Foxes played their song “Can I Believe You,” backed by a socially distanced, mask-wearing Resistance Revival Chorus inside the historic St. Ann & the Holy Trinity Church in Brooklyn, New York. It was truly beautiful. And so was the Wye Oak show at St. John’s United Methodist Church in Baltimore last March. Though news of the coronavirus was fairly regular at that point, the shutdown was still two weeks away. Little did we know then that this would be our last time out in such a large crowd for the rest of 2020.

+ + +

More recently this year, and closer to home, we learned that the iconic Mount Vernon Place United Methodist Church, a block away from our apartment, was being bought by a New Jersey developer for potential subdivision as apartment units. This would be a travesty.

The church building is listed as a significant historic site and landmark, and is apparently “one of the most photographed buildings in the state.” Standing out from its otherwise neoclassical surroundings, the United Methodist Church on Mount Vernon Place is an exquisite example of what is called Norman-Gothic Revival: Norman, in that it was designed in the style of Romanesque architecture developed by the Normans in the regions under their control or influence (northern France and southern England) in the 11th and 12th centuries; Revival in that there are no original Gothic structures in the Western Hemisphere as Europeans didn’t encounter the New World until after the Middle Ages; and Gothic because… Well, the term Gothic deserves some unpacking here.

Photomontage by Dereck Stafford Mangus, 2020.

The word Gothic has undergone so many changes over the millennia that it’s difficult for us moderns to grasp. The first Goths were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of Medieval Europe. The “civilized” Romans referred to these nomadic tribes as “barbarians” (the so-called “Barbarians at the gate.”) There’s so much to this early history of Goths that I don’t want to get bogged down with all the details here, so I mean no disrespect to my classicist or medievalist readers by glossing over it. The point is that these Goths had absolutely nothing to do with the ecclesiastical architecture found so abundantly in late medieval Western European buildings that their name is now attached to. That transition in meaning happened during the Renaissance when humanists used “Gothic” as a pejorative term to distance themselves from all that had occurred in Europe over the previous thousand years. The sixteenth-century Italian painter, architect, and historian Giorgio Vasari, for example, wrote of the “barbarous German style” in his Lives of the Artists to describe what is now considered Gothic. Two centuries later, the term morphed again when an architectural Gothic Revival inspired the literature genre characterized by elements of fear, horror, death, and gloom (the precursor to modern horror films). However, it should be noted that the late-medieval architects of European cathedrals were more interested in lightness and ethereal qualities, not darkness and cobwebs. But it was from this association with darkness that we get the late-twentieth century “Goth” subculture, characterized by heavy eyeliner, all-black clothing, and a preference for the music of Bauhaus, The Cure, and Joy Division. The original Goths would most certainly be confused by this cultural evolution!

My apologies for the long digression about the term Gothic, but I felt it needed some clarification. (Personally, I’m fascinated by etymology.) But my main point is that just as the meaning of a word can change over time, so too can the function of a building. That said, I truly hope the new owners of the United Methodist Church on Mount Vernon Place make every attempt to retain the beauty and grandeur of this historic building whatever it may become. A similar fate has befallen the nearby New Refuge Deliverance Cathedral at 1110 St. Paul Street, which was sold at auction this past July, a mere few “weeks after the June 5 death of the church’s founder and longtime senior pastor, Archbishop Naomi DuRant.”

The issue of church closures and what to do with the abandoned buildings is not just a Baltimore problem. As Jonathan Merritt writes in a 2018 article for The Atlantic:

Many of our nation’s churches can no longer afford to maintain their structures—6,000 to 10,000 churches die each year in America—and that number will likely grow. Though more than 70 percent of our citizens still claim to be Christian, congregational participation is less central to many Americans’ faith than it once was. Most denominations are declining as a share of the overall population, and donations to congregations have been falling for decades.

Photographs by Dereck Stafford Mangus, 2020.

Whether atheist, agnostic, devout, or lapsed, the urban explorer is continually impressed by the architectural glory that God has inspired. Church buildings accentuate the city skyline with a special kind of grandeur. Heavens-bound Gothic spires enhance the otherwise rectangular uniformity and neoclassical tendencies of apartment complexes, municipal buildings, and skyscrapers. I always felt like they were somehow closer to nature, like stalagmites in caves, or like the drip castles children make along the seashore. You don’t have to follow the tenets of a particular denomination to appreciate the elaborate exteriors of these beautiful edifices. You need not be a believer to find beauty in church architecture. What will come of buildings like the United Methodist Church on Mount Vernon Place in Baltimore? God only knows. For now, we can only hope and pray that they remain standing just a little longer so that they may continue to grace the city with their allure and charm.

This essay is dedicated in loving memory of my dear friend and mentor Don Schatz.

May he rest peacefully.