The Covid-19 pandemic has changed all of our lives in fundamental ways. We are surrounded by illness, death, staggering and unfathomable suffering, fear, poverty, hunger, isolation, and loneliness. So much of what we took for granted in our daily lives has disappeared. We have become prisoners of the virus.

Slought, a non-profit organization devoted to “engag[ing] publics in dialogue about cultural and socio-political change,” has begun an archival project and exhibition, titled Atlas of Affects, focusing upon both the banal and the traumatic dimensions of everyday life during the pandemic. Slought asked artists, in an open call, to submit work, in any form, reflecting their personal and emotional experiences at this dramatic moment in time.

When I visited the exhibit in November, it included some 29 pieces – art works in various forms and a number of texts – and a video. There also was a hand-out including statements by each of the artists whose work was displayed. My first impression was that there was something ordinary about the exhibit, but perhaps that was the point. Living in extraordinary times, trauma becomes almost mundane. Art, like practically everything else on the planet, is completely overshadowed by the armies of invisible organisms which have wreaked havoc upon our civilization.

On the other hand, there is a streak of hopefulness that runs through the exhibit. The pandemic has not obliterated creativity, and the work of many, if not most, of the artists who submitted work to Slought stresses resiliency and envisions a post-pandemic reconstructed world order.

A few examples from the exhibition.

Poetry of the Pandemic

There are a number of texts displayed in the gallery, which set the tone, and perhaps the mission, of the exhibit. The first stanza of one them, “Lamentations,” by Mary Jane Sullivan, reads:

To be a woman of constant sorrow unrecorded

To be a man of constant sorrow unrecorded

To be a child of constant sorrow unrecorded

“tHe gAThERing,” by Jaz, reads in full:

It’s

the struggle of their souls

Just to carve

construction

out of dust

Just to

paint rainbows

out of nothingness

Hang onto a comet’s tail

and wait for God’s smileJust to learn

the

language of roses

and

the nature

of

their children

As we wade

in the pandemic. . .

It’s the Spirt of Agape

that is our lesson. . .

Our

Legacy.

Terror and uneasiness in our world

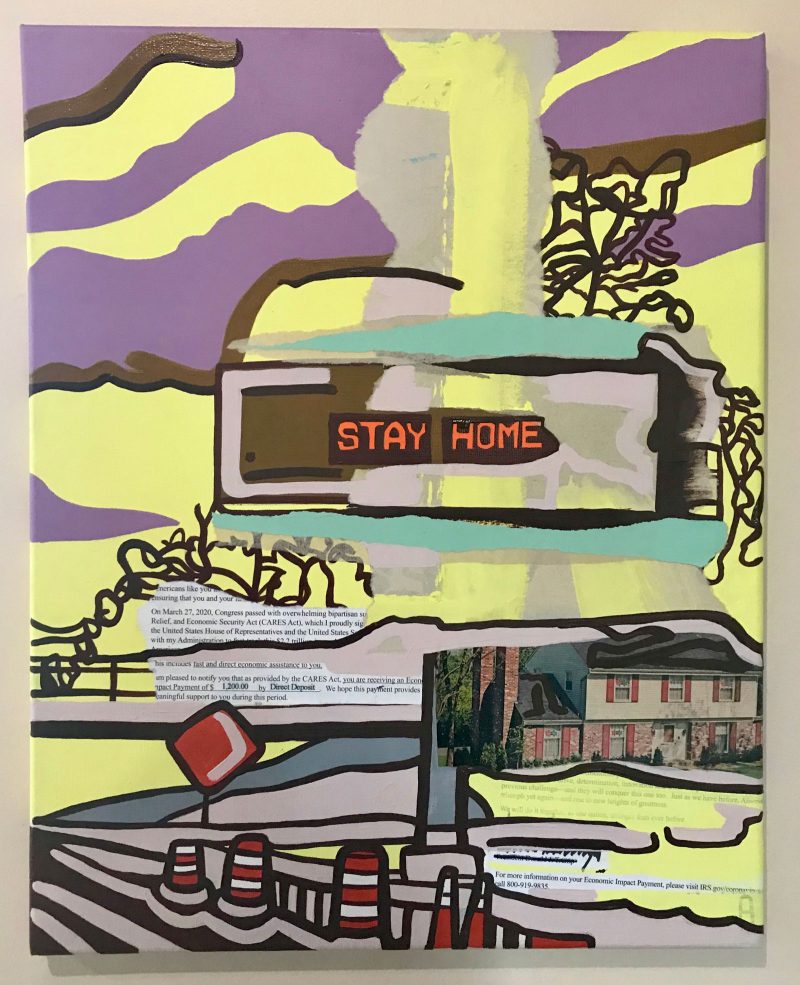

“Stay Safe” is a painting / collage by Danielle Cartier. “STAY HOME,” the piece proclaims, and includes embedded newsprint describing the CARES Act. Cartier explains that the piece “drew its inspiration from the signage along the major highways that were broadcasted for travelers throughout the pandemic. . . . Within the painting itself, I have included ephemera from the pandemic and I have used sickening sweet pastel colors to highlight the terror and uneasiness that the pandemic has brought.”

I was struck by the reverberating injunction of the roadside signage — STAY HOME – and by the artist’s recognition of the “terror and uneasiness” that we all face. It is as if we are experiencing the London Blitz (the 8-months of intense Nazi bombing of London during World War II) in slow motion.

Conjoined symbolism from religious, medical and other sources

The centerpiece of Clayton Campbell’s “Poets Among Us,” a Photomontage, is a homeless man (with dog) encamped in the middle of a below-street-level plaza of sorts, leaning over a book. In the background hangs a banner: Poets Among Us – Now on View. There’s an odd foursome of women surrounding the homeless man, pedestrians in various shades of purple (all headed in the same direction), and someone snoozing on a park bench, in the background. There’s also what appears to be a miniature Madonna, perhaps it’s Biblical Mary, wearing a mask, tucked into the bottom corner of the piece. It’s a captivating, if ambiguous, work, which made me think about the difficulty we all have interpreting the state of the new world we’re experiencing. Campbell’s statement focuses upon the helplessness, frustration, and strangeness we all feel, but ends with the thought that there may be unseen acts of creativity lost in the shuffle which will be part of our recovery.

Abstracted Landscapes

Bridget Purcell’s “Restructured Landscapes,” is an engaging montage which incorporates both notions of collapse and resurrection, envisioning the hope of a new reality created out of the ashes. She explains: “These images came about due to reflections on unrest. . . . it felt appropriate to quickly execute paintings on paper, rip them to bits, and reassemble the pieces into new structures on wood panels. I’ve been thinking a lot about structures falling apart, but also the creative impulses inherent in rebuilding. . . . To me, these pieces document the charged, anxious feelings of this moment while also making space to imagine what a new reality could look like, and what could potentially feel possible in the resulting landscape.”

Ms. Purcell, incidentally, was an Honorable Mention winner of our Art Writing Challenge in 2016.

Lockdown within one-hundred meters

One of the lockdowns imposed by the government in Israel during the pandemic precluded people from wandering beyond one-hundred meters of their homes. (Ed. Note: 100 meters is 109 yards or a little less than the length of a football field) In their “Lockdown within one hundred meters: A poetic reflection,” Daphna Levine & Roi Boshi include a digital photograph of a lush courtyard surrounded by buildings, with a mother and son walking through it, away from the camera, carrying provisions.

The artists noted that they “propose to view the extension of the home at the level of the immediate community and neighbors’ mutual gazes as the basis for a model of community resilience in times of crisis.” . . . [W]e propose recognizing the basic importance of the human encounter, of eye contact, struggle and solidarity among neighbors. This is a call for tolerance based on a narrative that lingers around courtyards, laundry lines, balconies, and trees.”

I have my doubts about whether the pandemic has created street-level conditions which breed tolerance of differences between peoples packed together, at least not in the United States. I do think, though, that the pandemic may have fostered for some a rejuvenated appreciation of the natural world, one reflected in the image created by these artists.

A moving vision of hope

There was only one media piece playing in Slought’s gallery when I visited (there are others in the archive) — Carmen Argote, “Last Light.” Self-described as “a meditation on walking and memory in Los Angeles, [t]he film explores notions of selfhood under the dual threat of contagion and isolation. Combining video and still images of an evacuated city with an intimate voiceover, the narrator reflects on feelings of vulnerability and betrayal, and draws on childhood memories to make sense of a city transformed. Over the course of the piece, day moves to night as the artist traces a path from demolition and sickness to envisioning a different world.”

Again, I was struck by the artist’s vision of hope beyond images of despair.

The film, produced by Clockshop can be view at clockshop.org

Artists in the time of coronavirus

In many ways, Atlas of Affects reminded me of our series Artists in the time of coronavirus, a 56-part on-line art exhibit in which we featured the work of some 350 artists between March and August of this year, including their personal statements concerning their experience of the pandemic. In the words of one of the artists, Matthew Rose: “It seems as if my work, though perhaps not apparent on the surface, has soaked up the culture of death and in so doing reflects my desire to reflect that and its complicated impact on our lives on the planet.

Slought has produced high quality prints of the pieces on display in the exhibit, and visitors are invited to take them home, and to share them with others.

The exhibition has been organized by co-curators Aaron Levy, Jean-Michel Rabaté, and Ella Comberg. While nothing is certain, they are hopeful that the gallery will be able to re-open in January and extend the exhibition through the end of the month. Let us hope.

Atlas of Affects: An archival project and exhibition about everyday life during the pandemic. This exhibition is currently closed due to Covid-19 restrictions. Learn more at Slought