Like many, I have spent the last year working from home, and trying to adjust to COVID’s impact on daily life. While I was an avid cook and baker in The Before Times, the last year has definitely seen an increase in my kitchen usage, from expanding my pastry repertoire to trying more ambitious savory dishes. In the absence of being able to be out in the world, I have spent time finding alternative sources of amusement, such as finding fun cookbooks. I am definitely not one to stick to a recipe, so I like cookbooks as much for the food inspiration (rather than strict direction) as the book itself: the object, the pictures, the anecdotes that are often shared between recipes. It is with this interest that I have begun gravitating toward a very specific subset of the cookbook genre: cookbooks by fine artists, or those inspired by art.

Food, certainly, is an art in itself. The mix of precision and creativity; the colors, textures, temperatures; the visuals of plating; the sound of crunchy crust. The parallels to visual art are multifaceted, and there are tons of books that explore the intersection of these practices. These include publications like Dinner with Jackson Pollock, which features not only gorgeous color pages of his artwork, but also recipes from the man himself (like his famous pasta sauce), with little stories about each one. Another favorite of mine is The Monet Cookbook: Recipes from Giverny, which includes not only recipes that Monet served to guests out of his yellow dining room (like the delicious stuffed tomatoes on page 134), but also photographs, excerpts from letters pertaining to select dishes, and related images of his art. While away from museums (and unable to travel), these and other books are bites of the outside world.

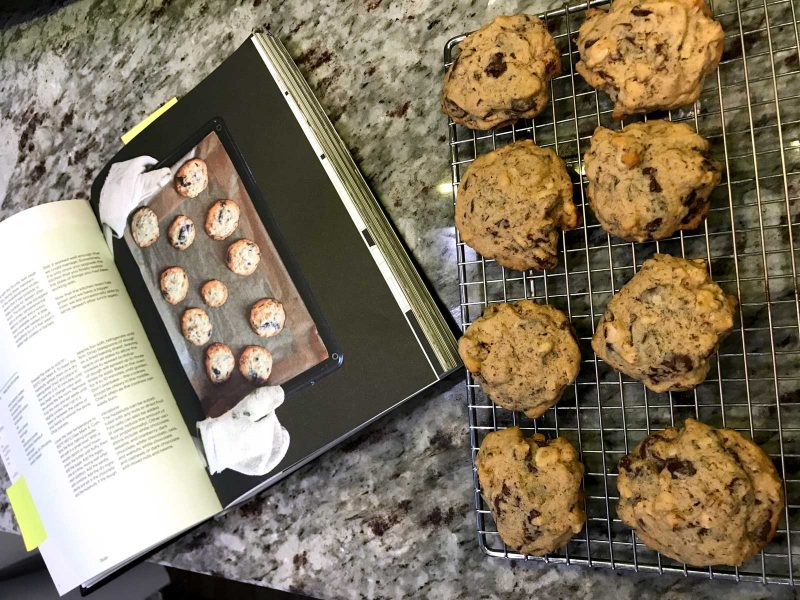

Within this category, the art-cookbook with which I have spent the most time during COVID is Studio Olafur Eliasson: The Kitchen. The soft, dark, fabric-wrapped book is definitely the most philosophical cookbook I have, though I suppose this shouldn’t come as a surprise given the artist from whom it originates. Eliasson is known for his large-scale works, installations which often use light and are inspired by elements such as air or water to create a dynamic experience. Eliasson’s cookbook mimics that artistic approach, instead applying it to food. In his introduction, Eliasson writes: “This book is a portrait of the studio kitchen. Yet it is also a portrait of the complex organism that is my studio from the perspective of the kitchen… [it] incorporate[s] the research, artistic projects, and food-thinking that take place in and around the studio kitchen” (p. 14).

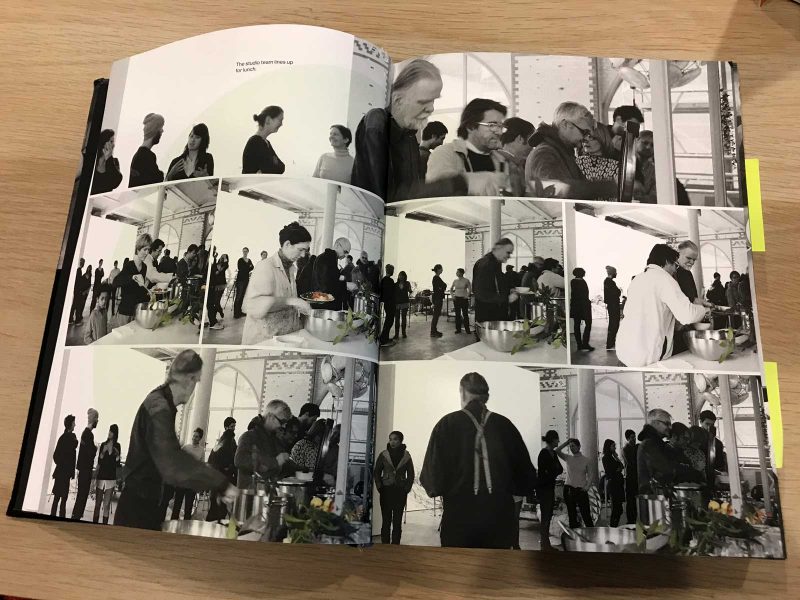

That, the studio kitchen, is the source of all of the recipes in the text. Each dish (sweet, savory, sides, and more) has at some point fed the artist’s large team. More than 15 years ago, the studio team (then about 15 people) would take turns making lunch for each other, and eating together. Since then, that number has grown to around 100 mouths, with assistants and guests mixing each day to eat together, and sharing cleanup duties while a dedicated kitchen team does all the cooking. This range of chefs and styles is captured in the book, with dishes influenced from a range of global cuisines and of varying complexities, though always using fresh, vegetarian ingredients and simple tools. The production scale is also reflected in the recipes, with each marked to feed either 6 people, or a whopping 60!

During COVID I have thought a lot about food. In pre-pandemic times, people gathered, shared meals, and went to restaurants. Since COVID, that has changed dramatically, not to mention the increase in food scarcity that so many have faced. So it has been an interesting time to work with this book – made from and intended for communal gatherings – to just cook for myself and my partner. It raises questions of sustenance: food as not only bodily nourishment, but also social and spiritual. How does that change in an individual versus communal creation and consumption setting? Similar questions can, of course, be asked about art. Looking at art online during the pandemic, while a reasonable substitute, is in no way equivalent to the in-person experience. Is art nurturing nonetheless? Of course.

There is a quote from Eliasson in the book that investigates food as an individual vs communal experience, that seems tailor-made for COVID: he said there is an “essential duality implicit in eating together: When I eat, it is an experience that is extremely individual. But by eating together with others, I situate my experience within a space that is very much collective… But since you have a different set of taste buds, a different body, a different history, and different preferences, your experience may radically differ from mine” (p. 43). Much like how I enjoy certain artists and you others, or how we would draw different interpretations of a painting, even while sitting side-by-side, food, in a different mouth or at a different moment, is totally personal.

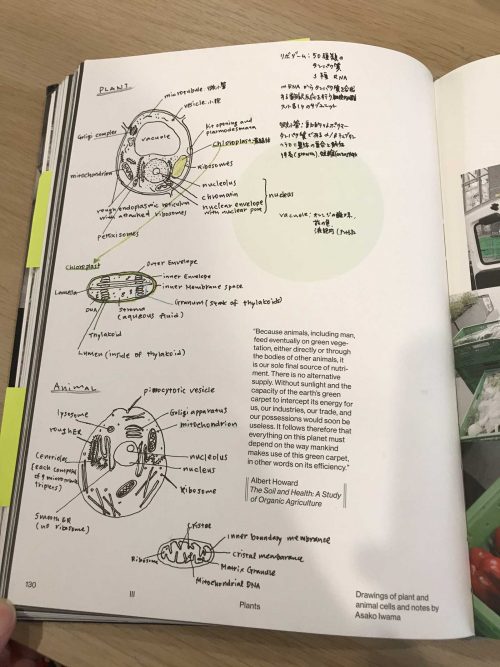

Other such philosophical sentiments pepper the text. After some introductions on food, art, and food as art, the book is broken up into eight parts (studio, body, plants, seeds, microorganisms, DNA, minerals, universe) with 3 categories in each: recipes, events, and encounters. For those who have experienced Eliasson’s artwork (perhaps at the Arcadia University Art Gallery in 2004), the nature-focused, even sublime language of these sections won’t come as a surprise. But, how to actually show something like “the universe” in a cookbook? That’s the challenge. Each section weaves in excerpts of other writings on food, science, or art which ground the theme, and then pairs those with related studio photos or artwork images before jumping into recipes. For example, section 5, microorganisms, features lots of mushrooms, fermented dishes, and yeast-based foods. The intro to this section includes a poem about miso, a reflection on bacteria’s purpose, some microscope images, and pictures of books on composting and fermentation.

In this book, scale is an idea in addition to a quantity measurement, and it is certainly flexible: microorganisms and the universe are captured in these pages, an acceptable substitute for Eliason’s usual gift of containing light in a gallery without confining it (or you). This artist is a master of mingling of the macro and micro. His installations often fill huge, airy gallery spaces, and involve multiple viewers occupying or passing through the space at the same time. However, despite this apparent largeness and communal set-up, the work prompts you to go inside, to reflect upon that scale and your relation to it, to digest the colors, temperatures, and lighting, to tune into your artistic “taste buds” and notice your physical responses and reactions.

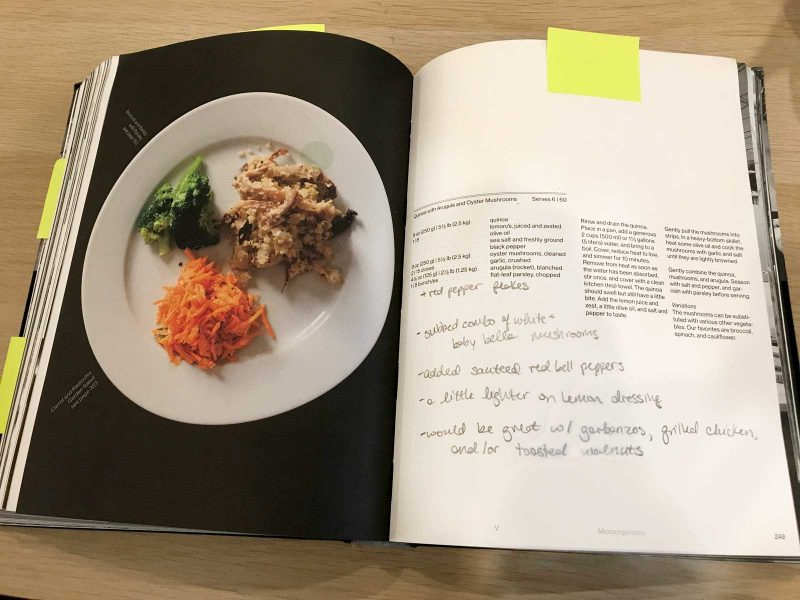

Flexibility – whether in variance in portion, range of content, or scale of idea – is something I appreciated in the text. Though the book does not directly suggest playing with ingredients or other recipe alterations, its thought-provoking philosophy seems to encourage improvisation. My experiment with one of the microorganism section recipes (Quinoa with Arugula and Oyster Mushrooms, page 249), veered slightly off the proscribed course. I changed the proportion of quinoa to mushroom, used a mushroom blend, added bell peppers, and went light on the lemon dressing. I played with temperature: first eating it hot, then eating the leftovers cold. My partner requested the addition of chicken, while I thought chickpeas or toasted walnuts would make a nice addition. Flexible.

Perhaps being flexible and finding art where we can should be two takeaways from the last crazy year (pretty big takeaway from a cookbook, huh?). Though this year of COVID has certainly created much cause for mourning, it has also expanded conversations and opened up thinking of what a “new normal” or post-COVID world might look like. From reconsidering working from home, to a forced look at the healthcare system in this country, to seeing the true value of the arts as part of daily life, people are getting new looks at the world. I hope that, as we conceive of how things might change in the coming months, an appreciation and understanding of the art of food (whether trendy sourdough recipes or artistic plating), continues to provide nourishment.