Diane Burko, known for her activist paintings and programs dealing with environmental issues, spoke with Susan Isaacs recently via Zoom. Burko has an upcoming live Zoom lecture at Towson University that is free and open to the public on March 25, 2021 at 6:30 p.m. and an upcoming exhibition: Seeing Climate Change: Diane Burko, 2002-2021 at the American University Museum at the Katzen Center, Washington D.C. August 28—December 12, 2021. Register for the Towson lecture.

Susan Isaacs: Hi Diane. So, we found we have a common interest. You discovered the work of Augustus Vincent Tack when you were in graduate school at Penn and were inspired by Tack’s abstraction of the landscape, responding to his lozenge-like shapes in your blue and white paintings. I wrote my dissertation on Tack.

Diane Burko: What an amazing coincidence. I loved visiting all his work at the Phillips.

SI: Let’s discuss your background. You began as a painter?

DB: Yes, I was a painter though I always used the camera, initially to document my work and to record what I was seeing and, for me, seeing was all about the landscape.

It was all about going out and being swept away by these big empty open spaces, probably because I was from the city (originally Brooklyn) and I never saw open spaces. I lived in an apartment building, and I was just captivated right from the start with these large vistas, these dramatic panoramas, and of course I had seen them in Hudson River School paintings in my art history books and classes, and also French painters who I knew quite a bit about so that’s where I began.

SI: So, from the beginning as a professional artist, you felt, you were a landscape painter.

DB: Yes, you know I painted the figure and the still life and all that stuff that you do in school, but I think the reason I latched on to the landscape is because it allowed me to be the most abstract.

It gave me the most control of what I wanted to do. Although I actually started graduate school as an abstract artist. I entered not with the realistic paintings that I left with, but with these very large pastel oil stick abstract images that were reminiscent of a combination of maybe de Kooning and Matta. You know, it was that era. Remember, I was doing work in the late 60s, so a lot of my teachers were second, third generation abstract expressionists, so I was very much of that school when I entered graduate school.

SI: And when you were doing that, did you think about content at all?

DB: All of the terminology and the theory that we now have in post modernism—all of that was totally absent in my education; it was all about the canvas, making the work, being involved in the work, I had no real awareness of where I was in the world, quite frankly. And I loved just making stuff. I fell in love with painting; it became a habit. The content at that point was the landscape.

The tenor of Penn at the time was to paint what you were seeing. I realized that after I got there. Landscape painting was a whole new world. Going to the Grand Canyon was amazing, and I think at the beginning, I was just responding to what I was looking at.

I always made photographs of the landscapes that I would visit, especially since seeing the Grand Canyon, flying with Jim Turrell. Jim and I met socially in the 70s, when we’re both very young and I told him I was going to the Grand Canyon. He said, “You don’t want to drive, you want to fly into the Grand Canyon.” He claimed he could fly so I wrote to him, we connected, and Arizona State University drove me up to meet him in Mesa, which is where he had his plane and it changed my life. It is more abstract to look at these patterns that appear when you look down on the landscape. Yvonne Jaquette was doing the same sort of thing—we had similar paintings at that point in time; I would take these photographs, bring them back to the studio, and paint from the photographs.

SI: So that flight was very important in terms of shifting your viewpoint.

DB: I always credit him for that of course. What Jim taught me is that I could make my own photographs instead of collecting them from National Geographic or books. Once I had that experience, I knew I loved flying. Jim helped me that way, to take my own pictures, but also reinforced the aerial view, which as you know is my preferred view. With climate change I began using Landsat images, mostly from NASA.

Photography became a separate medium for me in 2001 when 9/11 happened. I started looking at all my boxes of slides of all these landscapes that I had taken from the last 30 years. I had always put aside the ones I thought were beautiful photographs, as opposed to just source material, and I started making prints of those, but the slides were small.

I make big stuff. So, I purchased a four by five camera, and I started making film [images] and then luckily, digital really came into its own soon after 2000. I purchased a digital camera and then I was off, and I started making 40 by 60 archival inkjet prints. Photography became my other practice.

SI: Did you still use the photographs for making the oil paintings, or were they a separate body of work?

DB: Both, both.

Because of all my aerial work I had this collection of shadow photographs. There was always this cool shadow that you would see on the ground, as you were landing or taking off. I did a whole book with the poet Toby Olson, “The Shadow Under the Shadow,” his sonnets and my images.

Even in that period, where I was basically going for the image for my paintings, there were always photographs that would come out of that, and then I specifically just did photographic series, and I still do that now.

SI: When did you begin to think about the environment as an issue? When does the shift happen?

DB: I first thought of the landscape as basically just this great expanse to paint, but then I met my second husband, my partner for almost 30 years. He’s a landscape architect. He wasn’t that at the time, but he’s very bright and he knew so much about geology, nature and the West because he grew up on the Mojave Desert.

So, he would give me these insights about why the landscape looked a certain way—about earth science. So, my first kind of engagement with the landscape was from a geological, kind of scientific perspective—because I’m a curious person, and I was always asking him questions and, of course, you know I started with the Grand Canyon. You can’t get more into geology than that.

Through presenting all these talks and visits in recent years, it hit me that almost every landscape I had done for 30 years was about geological phenomenon. First, it was the Grand Canyon, then I did this huge series for years on volcanoes. There’s been this interest of mine in this monumental kind of landscape, so that is the first layer of my engagement with the landscape as environment.

But in an ecological sense—that didn’t really happen consciously until 2006. Elizabeth Kolbert’s book, “Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change” came out. I had been reading her essays in “The New Yorker.” 2006 is also when Al Gore’s movie about global warming, “An Inconvenient Truth,” came out.

And then I had this exhibition Flow at the Tufts University Art Gallery, Aidekman Arts Center, Medford, MA. And the exhibition was basically about the last project I had done, which was all about volcanoes, but the last country that I went to through a grant from the Leeway Foundation was Iceland, which is the most volcanic country in the world, but it’s also full of ice.

SI: Flow was jointly organized by the Michener Art Museum and the Tufts University Art Gallery and was curated by Amy Ingrid Schlegel.

DB: Yes, and when it traveled to the Michener, there was room for more work. Amy said, “You painted mountains of snow way back in the 70s didn’t you? And now we’re showing these Iceland paintings.” So, we added an early acrylic painting to the show, “Grandes Jorasses,” which was about 60” by 96.”

That is what I call my A-ha moment, because as I’m walking through the galleries, giving the usual museum talk, (I always say you can think of more than one level if you’re a woman), and I’m giving the talk and I’m looking at the snow and I’m thinking of climate change apparently, and I’m wondering if the snow is still on those mountains.

And that was that, so I went home. I had finished this project; what am I going to do next? I am not a “signature style” artist. I need to move on after solving something, I need to be really motivated on an intellectual and aesthetic level to be challenged. I was going to do something else. It occurred to me because of the climate change issue to look back at these black-and-white mountain climbing books that I had, some on the Matterhorn. That’s what got me started and then one thing led to another . . . The Internet was very much at play in my education. Geologists, ever since they had a camera, documented how a glacier looked over time, and documented how it changed. I started meeting scientists, originally asking permission to use their images, and that was the beginning.

I’ve been on that road ever since, so I moved basically from glaciers to coral reefs to a project that I was lucky enough to be invited to with friends from MIT where we went to American Samoa in the Pacific, and in Hawaii I visited the Ruth Gates Lab at HIMB. Every time I get involved in these things, I’m always reaching out to scientists who are very generous in giving me information so, I’m constantly learning.

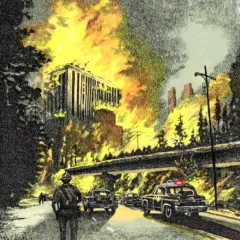

The ocean and coral reefs are something that I’ve been involved with since 2017, but this past year, my work turned to Covid. But what I thought I was going to be doing before Covid hit was exploring drought. I had spent a month in Chile in October 2019 visiting the Atacama Desert, as well as observing the salt flats and lithium and copper mines throughout the country—all touching on environmental issues. That year also included heat waves in Europe, Australian forest fires, and of course, our California wildfires this past year. Climate change is all inclusive, even Covid is all about climate change.

Right now, I’m doing a series on the Amazon forest burning. I was shocked, quite frankly, I mean I know my geography and my maps, but for some reason I didn’t comprehend deeply how huge a part of South America, the Amazon Basin is.

SI: And how it affects all the world.

DB: That I knew because I am an Alexander Von Humboldt fan. I saw the exhibition and watched the SAAM lectures. That’s one of the nice things about this crazy pandemic—I have really taken advantage of the zoom stuff.

SI: How would you describe your practice?

DB:Part of my practice is at the intersection of art and the environment, but public engagement is integral to it, to the point where I will not do an exhibition unless the museum or the university gallery agrees to commit to programming about the environment and climate change. I’ve had that policy for the last 15 years so that’s my social engagement part, and wherever I am showing my work I’m talking about climate change: ice melting and the ice sheets, forest fires, or the Amazon. American University is going to have a whole year of climate change programming in connection with my show, culminating in a symposium in November. They are having a kick-off virtual event this May and intend to continue past my show all the way through to next April 22, 2022 to celebrate Earth Day.