Susan Isaacs interviewed Jackie Milad, a Baltimore City-based artist featured in group and solo exhibitions nationally and internationally, on Zoom. Milad is also a curator and arts administrator. She recently showed her work in Philadelphia at the Arthur Ross Gallery, University of Pennsylvania in a group exhibition, Re-Materialize, and currently has work in a group exhibition, No Fair, at the Erin Cluley Gallery, Dallas, TX. She has several upcoming exhibitions this year, including, group exhibitions at SOCO Gallery in Charlotte, NC and Pro Arts Gallery & Commons, Oakland, CA. She has a one-person exhibition curated by Amanda Jirón-Murphy at the Arlington Arts Center, Arlington, VA. June 19 – August 28, 2021 . You can view more of her work on her website. And register for an online Q&A May 6, 6:30 PM Eastern, to hear the artist speaking with gallerist Erin Cluley.

Susan Isaacs: So nice to talk with you. It’s been a while. Again, when did you complete your MFA at Towson?

Jackie Milad: 2005.

SI: We have been in contact since then of course; you curated an exhibition for Towson University in 2018, “ISLA: Regarding Paradise,” and I receive your newsletter. But it’s good to catch up at this time and discuss your careers as curator, artist, teacher, and administrator in the arts, not to mention mother of a nine-year-old son. You have had success as an artist, you are getting some important shows and awards. Where do you feel you are in your career and what changes are you making if any and how are you balancing your various professional activities?

JM: At this point my focus, as far as my career goes, is on my studio practice and all the admin that goes along with that. I have always thought of myself as an artist first. I’m making changes in the coming year that will hopefully provide more dedicated time in the studio. I think the balance of all of that you mentioned has been difficult for the last 15 years. Especially when you marry and co-parent with another artist (a musician) it’s a whole other thing of coordinating individual needs. There are things that I need to negotiate and plan every single day in order to keep balance.

There has been this incremental shift in the way I prioritize my work in the studio, over my curatorial practice, teaching and even my full-time staff position at Maryland Institute College of Art (since 2016) as a career advisor. I love curating, but it really takes up so much of your brain, not just the analytical part of your brain, like the organization and planning, but also there’s the fact that you are using a lot of creative juice. I found it to be really hard to be in the studio consistently during my days as a full-time curator.

It’s a matter of constantly reassessing schedules and needs. I’ve become an expert at finding these little bits of time to work in the studio. Even an hour during my lunch break from my job. And I don’t mix my studio with my career admin time. I am very disciplined about the (studio) work versus admin, as in applying for grants or applying for opportunities, communicating with galleries or curators. Then there is also promotion and marketing. I have to fit that in as well, like doing Instagram. It’s a lot of work but keeping boundaries and staying disciplined is what it’s all about.

I’m really grateful there’s been an increased demand for my artwork, but it’s so important to have and communicate clear limits. That means saying no to opportunities that just don’t make sense, in terms of timing or my ability to deliver on deadline.

SI: Let’s talk about the relationship between your curatorial vision and your own work.

JM: Curating kind of found me. I started when I had excess space in my studio. This is before grad school, when I was running a fine jewelry design and manufacturing business with my dad, and we had a lot of extra space because my dad is obsessed with having as much space as possible.

I had no idea what curating really meant. A friend of mine and I decided that we would start, just for friends, a gallery (Chela) that would support our creative and experimental work, and to be in a Community. It became obvious that we were filling a niche, a need in the city at the time. This is in the early 2000s when there wasn’t a lot of support for the arts in Baltimore. We were one of a few artists-run venues in town. It was a very different time. The Transmodern Festival (which I co-founded) came out of that, and a lot of important networking for me as an artist and as a curator happened in that time.

Of course, I received my MFA in painting in 2005, and so there was more formal education happening during that time too. Including mentorship from you, Susan!

It is because of the collaborative work at Chela and the Transmodern Festival, I began curating as a profession for the gallery at Goucher College in summer of 2006.

SI: And you went to the Stamp Gallery at the University of Maryland in 2008.

When you were at the Stamp Gallery, you became even more interested in artists of color. How does that curatorial experience relate to who you are as an artist and to your work?

JM: In the early 90s, when I was in school in New York, identity politics was everywhere. I felt pressure from faculty to address my identity more in my work. And at the time I was, and I still am to some degree, a reactionary person. This really rubbed me the wrong way, to be told what kind of art to make. Mainly, I avoided making identity work because it would be obvious—being a child of immigrants, a person of color—multiethnic, multi-racial woman. And that seemed very restrictive or pigeonholing, and at the time I wanted to make work that could be identified or understood by anyone approaching it. That was my thinking at the time and even through grad school. I was making a lot of these works that were about body language and facial expression and being very playful about that too, trying my best to remove any kind of identifying details that might be associated with gender or race.

Eventually I got to a point, and I think it was partially because of curating and working for a large diverse institution like the University of Maryland, I found myself gravitating to artists who were really invested in making work not only about their identity, but also broader social justice issues, and these same artists were not apologizing for the politics they were bringing up in their work. I found this to be very powerful and inspiring. And then we entered a toxic political time in 2015-16, and it coincided with me spending more time in my studio. In all seriousness, it also was a time where there was a lot of chaos in my life personally because of having a young child, and a lot of other things. Now it has become imperative in my mind to make work that is political and addresses identity, history, and the body I inhabit.

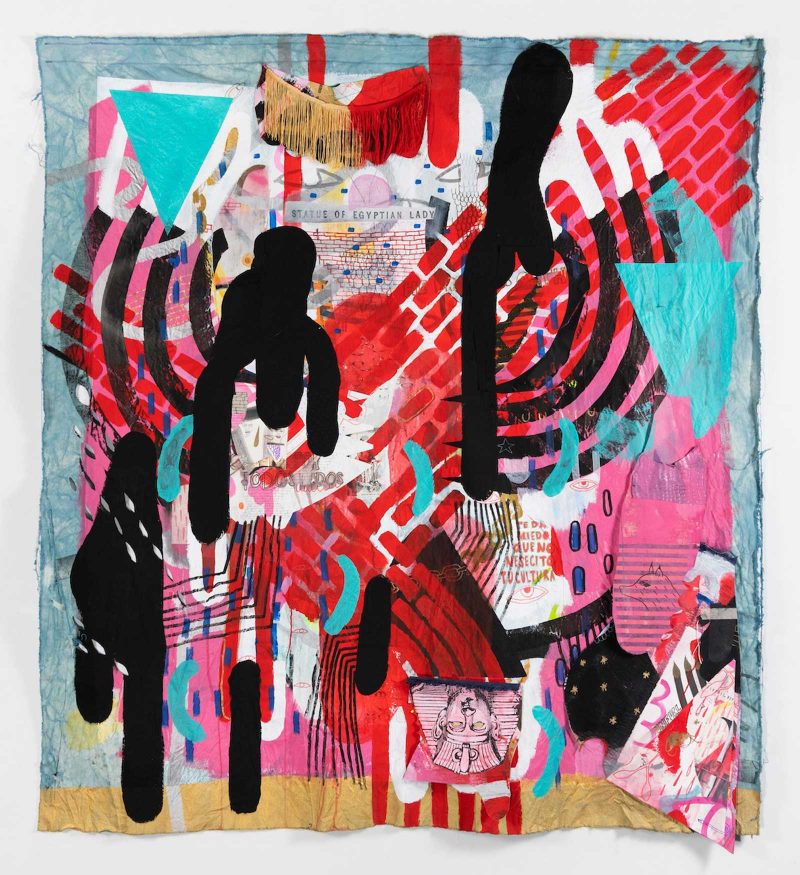

I think of my current work as personal, and I don’t care that it is super self-referential. I’m using symbols that are really relevant to me as an Egyptian-Honduran American woman—and frankly, many of these symbols and language might not be understood by most people, and I don’t care. Maybe it’s just being 45, but now I too am unapologetic about the work I make.

SI: How do you make your work?

JM: Most of the drawing and painting I do now is on canvas, and I layer collage on top using pieces torn from my older works made on paper and canvas. I have a hefty archive that spans twenty plus years that I pull from. Earlier on in my career, I only used paper, because it was the most immediate thing that I could get my hands on, and I really like the way paper feels. I transitioned to canvas in 2019 because I wanted to create larger works. I also wanted my works to read more as tapestries, flags, or banners. The average size I work with is about 72” x 72”, but I’ve started to work even larger than that. My canvases are hand-dyed, frayed at the edges and unstretched. I use gel medium and sewing to attach my collage components, so I don’t stretch the canvas, because that would ruin the collaging. The layering and fragmentation of collage is conceptually important because first it serves as documentation of my decision-making, the history of my hand, and my life. I think of the work as a living record of my experiences, including drawings on the works by my son, Piero. Secondly, it relates to this idea of what it’s like to be a mixed racial/ethnic person in this complicated country and using my story as an entry point. Doing this work with canvas has slowed my process down a lot, where with paper I could just go at it and it was immediate, now I have to wait for things to dry, and take my time.

SI: Are the colors symbolic for you or is it just that you are attracted to them?

JM: I am really attracted to red and pink, there’s something kind of grotesque about over doing pink, in my opinion. It’s sort of like the interior flesh. Not skin color but the color within. I like also the push and pull or vibration of these colors. I like to think I’m creating chaos with my palette.

SI: What do you think about when you work?

JM: In the moment I’m not really thinking too much of anything to be honest, except for the tool I have in my hand and where I’m going to put it, you know. I work intuitively. I don’t do sketches or plan a whole lot beforehand. I spend a lot of time looking and thinking after I’ve spent the day working on a piece. I also spend a lot of time mining symbols online and at the library, from various sources to use later in my work. These symbols mainly come from Egyptian culture, ancient to modern, current events/politics, Coptic Christian visual symbols, and lately poetry by Honduran poet, Clementina Suarez.

Very important to my process is also listening to music very loudly in my headphones. Often the lyrics of a song make their way into my works. Because l am married to a musician, I’m very lucky to have quite an eclectic collection and knowledge of music spanning every genre.

SI: You have a residency coming up. They are allowing you to take a leave from your job at MICA.

JM: Yes. I’m really excited about the residency. I’ve worked out a plan with my job at MICA, being virtual really helps matters. It’s a two-month residency at the McColl Center for Art + Innovation in Charlotte, North Carolina. Two glorious months to read, research and make art. It’s a family friendly residency, which is even more awesome and unique. We’ve worked out a plan to have my family come down for a couple weeks at a time here and there. My husband at one point was like “We’ll come down for the whole time, and I can play music in your studio,” and I was like “Why? You don’t need to do that.” I’ve become very protective about my upcoming two months of paradise, hoping for a balance of time on my own as well as family time. Family friendly residencies are hard to come by, so I’m really grateful for this opportunity.

The residency that I did at the Vermont Studio Center in 2015 changed the trajectory of my work completely, and I was only there for two weeks, and in two weeks, I was able to make six months’ worth of work. So, I think it’s hard to imagine what’s going to come out of the two-month period at the McColl. It’s a super generous residency.

Building and creating relationships with new people, ultimately is why residencies are so important. Opportunities for growth in our careers happen because of the people we know and support.

SI: It sounds like we need to talk again in a year to see how your work has changed as a result of this residency and the relationships that you continue to develop.

JM: Yes, it would be my pleasure to chat and share my progress with you Susan. Thank you, for taking the time to chat with me today and for your interest and unwavering support of my work.