Janyce Denise Glasper is an artist and writer and part of Artblog’s team of contributors. Imani Roach is an artist, writer, educator and former Artblog Managing Editor. Janyce and Imani spoke with each other after a prompt we suggested to our contributors to try writing collaboratively — as a way of getting to know each other better and as a way to relieve at least in part the isolation many of us creatives are feeling during the pandemic. This dialog piece below is the result of Janyce reaching out to Imani, her former editor, to catch up and discuss issues. Janyce, who is currently based in Dayton, OH, and Imani, who is based in Philadelphia, spoke with each other via Zoom in late February, and this dialog is a transcript of their conversation, edited for length and clarity. We hope you enjoy it!

— Morgan and Roberta

Janyce Glasper: So how are you doing in Philadelphia? Are you still a part of Vox?

Imani Roach: I was briefly in Ohio as well by the way— in Toledo for about three months. Right now, I’m in Philly and still a part of Vox. I had a show there that opened in March 2020 three days before the shutdown. That was the last time I was out with people.

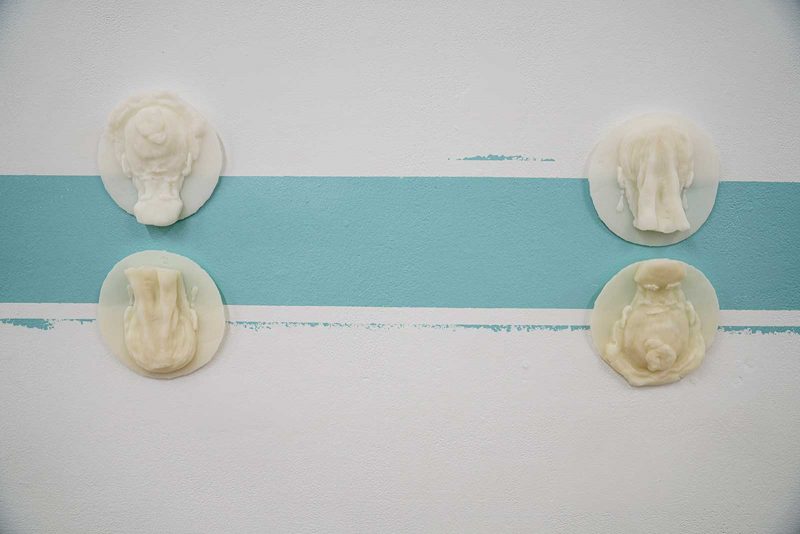

In terms of my visual arts practice, I was collecting cut flowers from December of 2019 until March and incorporating them into my work. After everything closed down, some floral arrangers filled Rittenhouse Square with donated flowers from canceled events— weddings, graduation parties— probably $10,000 worth. A limit in my show [at Vox] was that I couldn’t get enough flowers. I wanted more. I always think big. For example, I was once going to fill a room with an insane amount of little miniature wax sculptures.

So I did take flowers [from Rittenhouse], a dozen over the course of five or six days, not disrupting it too much. There were literally thousands of flowers. It was incredible.

I was relating flowers with mourning and grieving. Whenever we lose a person or a job or anything central to our identity, it can feel like losing a part of your body. Yet sometimes you can still feel it. A flower is disconnected from its roots, but still thinks it’s alive— the petals are drinking water and soaking up sunlight. Those flowers from canceled events brought about what we do with lost moments.

Janyce Glasper: In the meantime have you been performing at home? What does quarantine do to someone with a voice like yours, having these periods of not being able to do the things that you’re used to?

IR: I am also a performer.

I was never full-time, but being a musician was a pretty significant side hustle for me. The music industry— the local music industry—has been hit harder than most creative industries. Philadelphia’s music scene relies heavily on live performance. Philadelphia is one of the few cities in the country like Chicago, Los Angeles, New Orleans, Nashville, and New York where you can make a living as a non-famous working musician. You can give lessons and perform full time without having to put out a record or get radio play. However, that requires gigging constantly. That has been shut down.

I’ve done a few Zoom concerts— a visual recording session with everyone recording their own parts separately and then it gets edited together. I also did performances for a LGBTQ+ awards banquet and a Juneteenth piece. That was current members and alumni doing a version of the Black national anthem. I did sing a little bit—it was all me standing in my apartment by myself. The actual process feels alienating. You’re constantly reminded, “They’re over there. We’re not actually together.” I’m singing my part over and over alone until I get it right enough to send off. The final result is always really satisfying.

Aside from the arts, my other area of labor is education.

I was listening to a BBC World News report on education funding in South Africa. They were talking about how the government woefully underfunds schools to the point where 70-80% of schools don’t have adequate books, computers, or wifi. More than half of them don’t even have functional facilities including bathrooms.

A student activist being interviewed questioned a member of the department of education and was basically asking, “where’s all the money going? Why isn’t this being prioritized?” The minister answered, “well, we were putting money towards it.”

I found myself getting frustrated. It felt very similar to Philadelphia where the school system is failing. There’s so many excuses for why there isn’t enough money. There is never enough money for what are oftentimes the most important.

JG: Right.

IR: Education is a “must” infrastructure. By infrastructure, I mean like roads, public transit, accessibility. Many crises in Philadelphia feel more urgent. One thing that the arts have in common with education is that it’s about planting seeds for the future.

There isn’t enough money to do everything, especially in this pandemic, especially with this economy. I think we really need to recognize that. There’s been discussion in Philly about the relationship between the funding, say for the police and for other item lines on the budget. People use the crime rate in Philly as an excuse for the police budget. If there was better infrastructure, if there was more funding for the arts, we wouldn’t need as many police officers.

Yet Philly is a city where you can actually be a working artist without being famous, particularly the music scene. In Philly to be a working visual artist and not be famous, you also have to be either attached to some non-profit or university, which will oftentimes suck your psyche dry. A lot of people are doing that work. And those are the people who make Philly a good place to live.

JG: I was thinking about your urgency on the importance of education and believe that the arts are also. That’s why they have been getting rid of so many arts curriculums.

IR: Yeah, that’s hugely important. You’re right that education and the arts are not necessarily separate. They overlap in terms of value and in how they’re often devalued. Art in schools is a particularly at-risk category. It will matter the most in the long run, but gets left to last when they’re handing out money.

What is required for the people who are in power to actually be willing to give up some of that power? Oftentimes power has a way of conferring wisdom and correctness onto the people who have it. It’s hard for people in power to make these decisions about budgets, to change their ways. They would have to actually be open to considering that they don’t know or be open to listening to artists. And considering that I didn’t use to think that art was important, I’m seeing differently.

JG: Well, those in power have their own internalized hierarchy. They already have this set of ideas of what’s important, especially those in power who have grown up with wealth. So they already have a notion of what is most valuable and will probably put art and education at the bottom of their lists.

IR: Yeah, absolutely. Also, very few people get into positions of authority by focusing on the arts and education.

JG: What does the future look like for us? How can we as artists, individuals, educators, writers, and etc. reshape our future with the seemingly limited capacity that we have?

IR: You might as well have just asked me the meaning of life!

JG: Well, in ways of the crisis that we’re in right now is there anything that we can do?

IR: I have identified as an artist basically since I was born. For the last ten to fifteen years, people say, “You know, the role of the artists that you imagine is not possible, right?” or “You’re an artist, use your creativity to imagine a different world.”

It has not always been clear to me what the connection between artistic creativity in specific media, like film, music, or visual arts has to do with world making. My own artistic process is internal, introverted, and small; more analytical in its approach. Am I going to change the world? No, I’m going to be realistic.

The gift of creativity, of art making is something that no one can take away. So I do think that we can improve the quality of people’s lives incredibly. I’ve been more focused on the impact of the arts on individual hearts.

JG: Yes. Yes. There are things set in place that will take centuries to dethrone or dismantle, especially when I think about art history, but there’s definitely a way that we can change them. Hopefully in the future.

IR: Yeah. I’ve been trying to push myself to be, “what does it mean to be creative outside of an artistic context when it comes to feeling?”

Oftentimes because of our gender or race, we are told your life’s supposed to look like XYZ thing. It’s hard to break out of set expectations. Maybe the first step in figuring out what to do in a crisis situation like this as an arts community is to try to identify the limitations that we have accepted and never questioned.

JG: Maybe some of us have other tools that we don’t even know that we have in terms of being resourceful and trying to survive and thrive.

IR: Yeah. There is that question of individual resourcefulness.

Part of what it is to be an artist is to be resourceful. Maybe we have something to offer, not just in our own community, but to other people in terms of survival strategies.