Senga Nengudi: Topologies, organized by Lenbachhaus, Munich and on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art May 2-July 25, 2021 deserves to be a blockbuster. Nengudi is one of those rare artists whose work is of interest to the most sophisticated art world visitors, and equally to a general public of all ages, including children. Everyone can recognize her materials sourced from friends, thrift shops, dollar stores and vacant lots and can appreciate the breadth of ideas with which she invests them. Her work speaks in the language of abstraction to themes of bodily awareness, African American experience, particularly that of Black women, communal activity, and the ephemerality of life.

The exhibition opens with a boom: “Black and Red Ensemble” (1971) a room-sized environment of nine huge, glittering, black, polyethylene drapes hung within the reddest environment ever seen: red walls, red floor, red lights — nail polish gets no more shiny or intense. Fire engines, night clubs, horror movies; pick your own reddest dreams or nightmares. And this is art you can touch. Viewers are encouraged to brush past the drapes as they move through the space. It opens a range of Nengudi’s themes which will reappear throughout her work: a multi-sensory appeal and, hence awareness of the viewer’s body; structures involving tension and release; an invitation to audience involvement, and a performative quality, in this case the work itself is the actor. The drapes which hang throughout the space will be rearranged during the run of the exhibition. It reminds us that immersive, participatory art needn’t involve video or computers; the primary material here is the artist’s imagination and her generosity to her viewers.

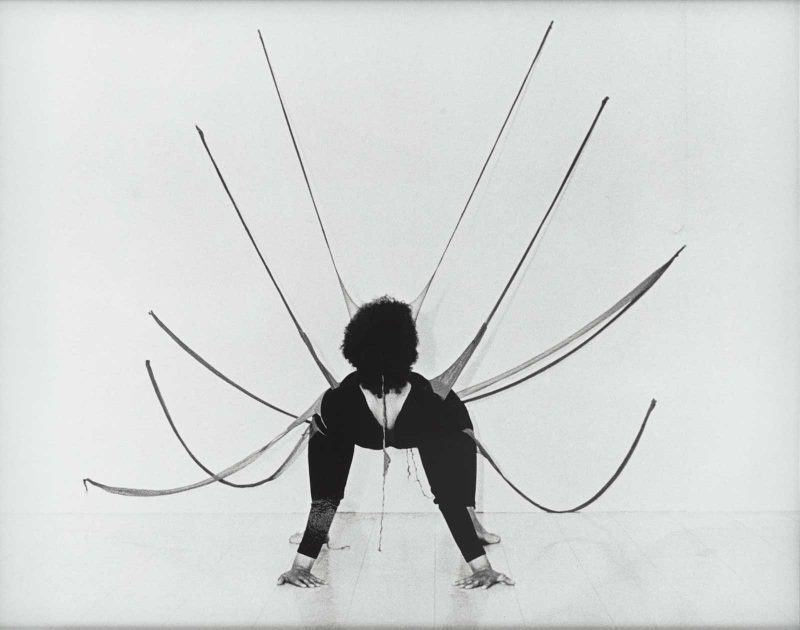

The next room displays Nengudi’s “Water Compositions”: malleable, vinyl containers of colored water – some of the larger ones suspended with huge ropes, others resting on plinths or on the floor. They were intended to be handled – no longer possible in the museum context – emphasizing their unfixed form. Nengudi was among a range of artists in Europe, Latin America and the U.S. who worked against the tradition of sculpture as solid, singular objects displayed on pedestals, as well as Minimalism’s hard geometry and industrial manufacture. She was also the rare American who had spent time in Japan. She had been inspired to go by her knowledge of the radical, post-war work of the Gutai movement in visual art and would discover Butoh dance, another post-war expression that would also inspire her. She has also spoken of the importance of the exhibition African Art in Motion at the National Gallery of Art in 1979. The scholarship of its curator, Robert Farris Thompson, became fundamental to an understanding of African and diasporic aesthetics. Nengudi became particularly interested in the ritual use of objects in African cultures.

Artists during the 1970s questioned distinctions among categories of the visual arts – painting, sculpture, film – and among the various arts – visual, musical, dramatic. They rejected traditional art materials and techniques, permanency, art world settings and audiences, and singular authorship. By the 1970s, women were also rejecting the idea that only men could be significant artists. Examples include Eva Hesse, who suspended a balloon in netting and a tangle of rope dipped in latex – and whom Nengudi credits as an influence; Christo, who marked huge, natural environments with fabric hangings and boundaries; Lygia Clark, who created objects to be handled interactively by groups of people and soft objects to be experienced by touch across the entire body; and Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who defined women’s housework as art, and offered to clean for museums.

You can read Part 2 of this review now! Check it out here

‘Senga Nengudi: Topologies,’ May 2 through July 25, 2021, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Main Building – Dorrance Special Exhibition Galleries