“I adapted to prison life but I wasn’t conditioned by it.”— Emmy award winning actor/director Charles S. Dutton to L.A. Times, Jan. 18, 1990

In 128-G: Art and Writing From a California State Prison’s tender foreword, Joel Baptiste, the supportive Calipatria State Prison cohort, convincingly drives home the important validity of art’s historic influence, stating that, “art has taken complicated knowledge from the upper class and interpreted sentiment sometimes even healing to the masses.” Enter whose voice matters most when it comes to art and writing. The work of inmates would most likely be considered the least valued.

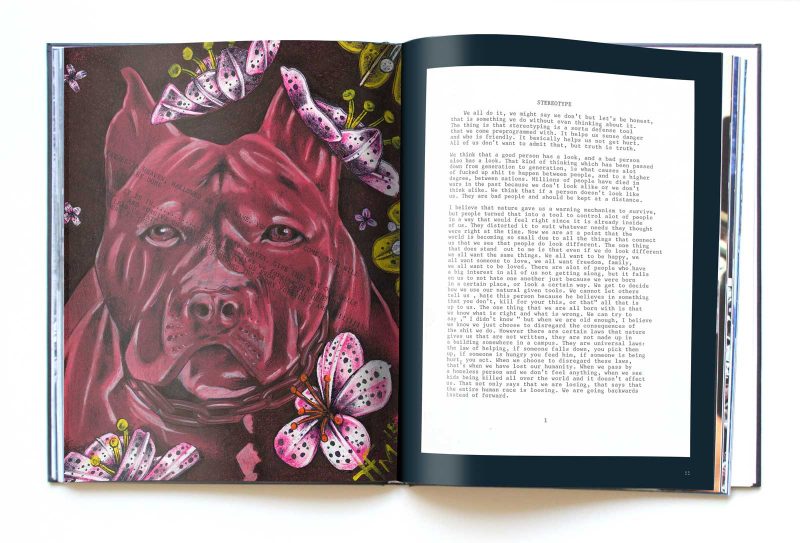

128-G: Art and Writing From a California State Prison is not a crime novel or a defense attorney’s manifesto. This unique book sets to redefine a complicated perception, to perhaps shift the minds of those fearing or revolting against lawbreaking criminals, that certain folks are unworthy of a second chance. Straight from a specific cell block, several men share abrasive accounts that push and pull at the conflicted reade. Brutal, heartbreaking stories are integrated between incredibly rendered drawings and beautiful, poignant prose shining through the cracks. Beneath the perceived societal villain exists the aggrieved human soul, the empathy, the endless regret. Television, film, and other media often show a quick and easy ploy— here are these caught criminals that will be locked up— justice is served. Behind the scenes of that justice is a grittier picture or, as Juan Mejia, the leading producer of this ambitious project, states, “the court gives physical punishment, but here [prison] is the psychological—there’s no end date for that.” The intimate portraits displayed page by page combine representative narrative and abstraction; religion ultimately the stepping stone from dark, oppressive slumbers; peace being found in the mundane ugliness.

The biggest takeaway is that the past should not forever define anyone’s future.

Mejia adds that prisoners are viewed as caged monsters that cannot ever be reformed, much less ever successfully reintegrate into society. The charged writings and artworks of 128-G convey an eagerness to express the weight captivity has on sanity. The only solace is creativity.

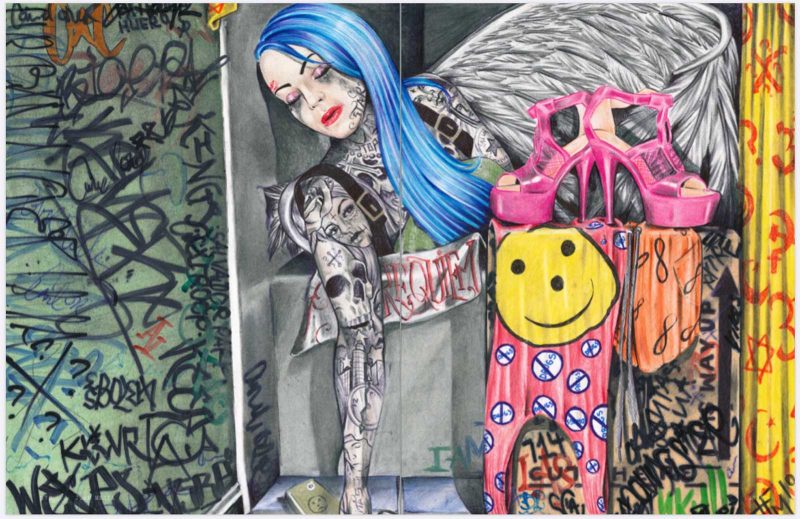

Art earlier interested these men, but life’s hardships interfered, and art now soothes them again in time of real need. Art brings them together, connects them in a healing tapestry. Their artistic styles are eerily similar— heavy interest in women, religion, tattoos, graffiti, text, and numbers. Cory Sullivan relays a story about his friend accidentally destroying gorgeous drawings with hot coffee. This friend happens to be Nick DiMaggio who later compares lost artwork to becoming a prisoner in the aptly titled essay, Art, History, and Coffee. Elias Arzate envied his artist mother; Jose Macias admired murals on his walks to school; and Richard Reyes wanted to emulate his talented older brother. These men know art and art history from both the outside and inside. Justin Kirk mentions that Jackson Pollock has always been his favorite artist and Cory Sullivan accurately describes the neoclassical Jacques Louis David painting— The Death of Marat.

“A famous painting was done in France in the 1700’s depicting the scene of a political pamphleteer and activist slaughtered while he took a salt bath…. he was writing a manifesto in this salt bath when a woman stabbed him in the heart,” Sullivan reveals.

Again, most of the drawings in 128-G feature women as the primary focal point— angels, sensuous pin-up figures, or floating head studies on stark white paper. So The Death of Marat is appropriated into a piece called Requiem. A blue haired, heavily tattooed woman and pink kitten heels are the main characters in an otherwise dark composition steeped in graffiti. However, the sexism is apparent, especially in Sullivan’s description. Jacques Louis David didn’t physically incorporate Charlotte Corday, Marat’s assassin, into his masterpiece, focusing on Marat’s secluded death. Corday is solely a name, invisible. Requiem has the woman take Marat’s place, her eyes closed either in sleep or death.

Motherhood is another role for women to portray— modest and saintly.

“Our actions never end at their doing, like throwing a small pebble into a body of water the ripples caused by the impact travel from shore to shore,” Nick DiMaggio expresses in his poignant essay Mother of Our Sorrows, “Perhaps they carry on forever in ways we can’t even comprehend.” He has also drawn a raw portrait of his own mother clasping onto a rosary, a sorrowful expression on her downturned face, a parent grieving her son in an unexpected way. In prison tomorrow is not certain.

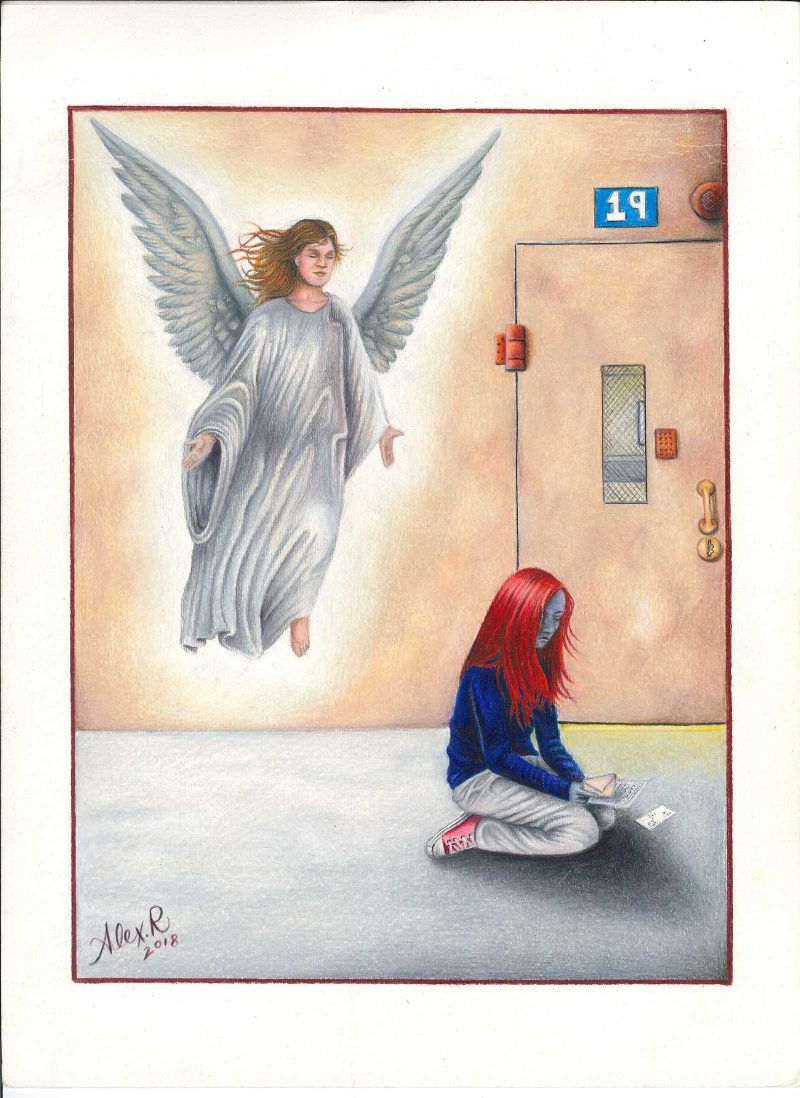

Unlike the other contributors, Alejandro Ramirez does not pen any stories or a short introduction to himself. Instead his one quiet illustration speaks volumes on isolation. An angel looks down on a sad redhead girl reading a letter in a stark, empty room. The girl is either unaware of the otherworldly presence or purposefully turning away, maybe to hide her sadness or the contents of the letter.

128-G: Art and Writing From a California State Prison may be a difficult pill to swallow— drug abuse, invasion of privacy, and daily peril are among the graphically discussed. This book is an important and necessary tool, a future learning resource. While some freed convicts can no longer vote; struggle finding a decent job or a stable home to raise a family; or migrate through societies that moved while they were stuck behind a cell, the stigmatic stains of their crimes, however minor, however large, are as bright red as Hester Prynne’s “Scarlet Letter.” The incarcerated have an even greater enemy within the disparaging public eye. Yet history has celebrated figures who have gotten away with violence, oppression, and abuse—often sans remorse and reflection— and the biggest criminals are rich white men who have even held political offices. Most of the celebrated criminals are pictured on the money we use. Some are in textbooks depicted as heroes. Some are in our music and film collections.

Arzate, DiMaggio, Kirk, Macias, Mejia, Ramirez, and Sullivan have committed terrible acts. They also remind us that whether we may or may not know convicts in our own personal lives, they are human too. They can obtain redemption and showcase compassion. These inmates are artists and writers expressing guilt and regret in the most motivational way possible—through instrumental creativity. Their steadfast determination to make amends is quite profound and inspirational.

Brick of Gold Publishing publishes the art and writing of incarcerated people. Their new book,’128-G: Art and Writing from a California State Prison,’ a hard-back book, is available for $35 at their website“. Profits go to support Words Uncaged.

[Ed. Note: This just in from the publisher of 128-G: …”We just posted the first ever NFTs from incarcerated artists. There are three of them. All three are images from 128-G. Here is an article I wrote about it…And here are the NFTs…” Check out Lincoln, by Juan Mejia on Instagram!]