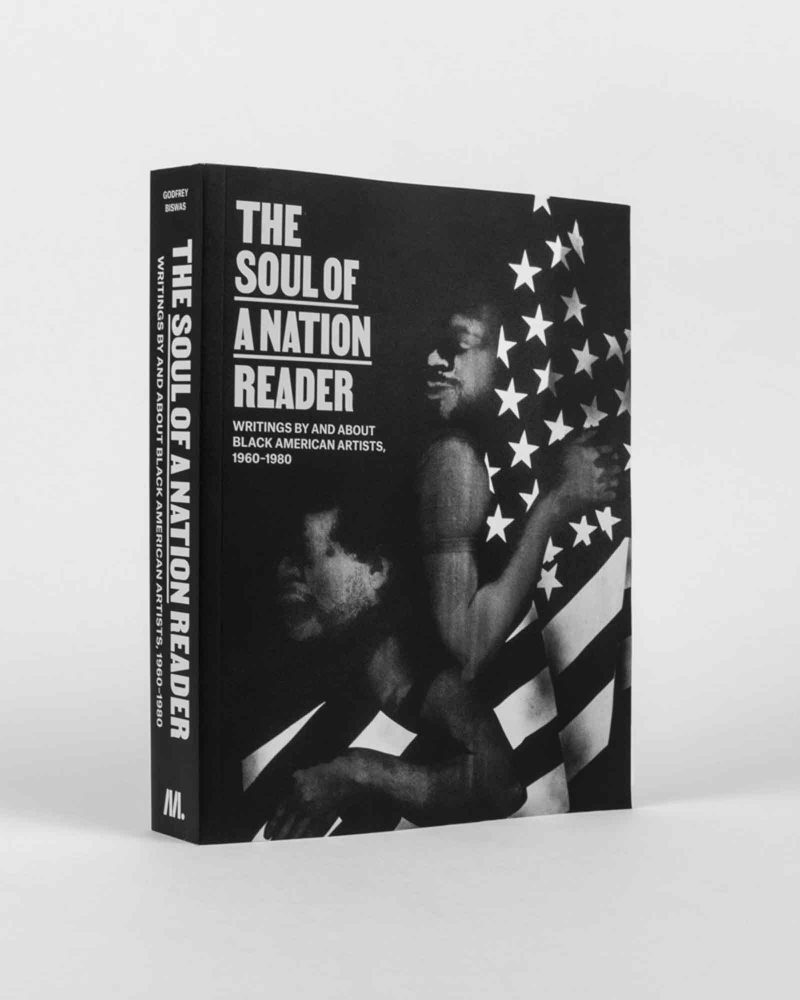

Mark Godfrey and Allie Biswas, eds. “The Soul of a Nation Reader; Writings by and about Black American artists 1960-1980” (Gregory R. Miller & Co., New York: 2021)

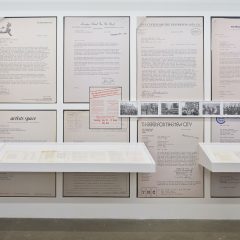

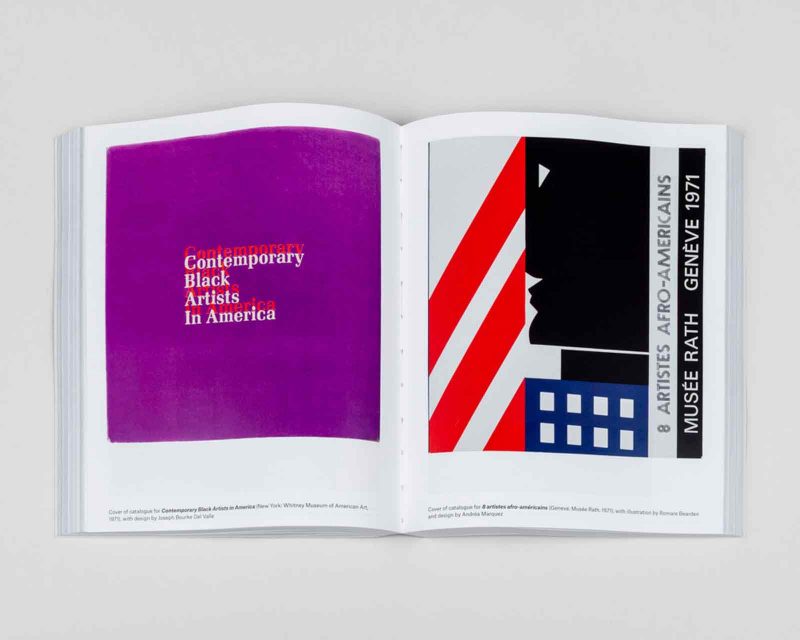

Filling the racial gaps in traditional art history requires, among other resources, access to literature on the field. As Mark Godfrey discovered when researching art from the 1960s-1980s by Black American artists for his important exhibition, Soul of a Nation; Art in the Age of Black Power (Tate Modern and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, 2017 and U. S. museum tour), the material was often extremely difficult to track down. Some writings could be found in Art in America, Artforum, Time, The New York Times and other readily-available books and periodicals, but much was originally distributed in small periodicals, pamphlets and catalogs for exhibitions at small museums and galleries, self-published as well as unpublished press releases, opinion pieces, statements and announcements by artists and artist-run organizations, in lectures and on radio programs. The authors have done a tremendous service in collecting this material. The volume begins with Godfrey’s introduction, which gives a particularly clear outline of discussions about the contested subject of Black American aesthetics, among other topics. Biswas contributed valuable introductions to each of the more than two hundred writings, situating the authors and circumstances in which the texts were written, delivered and/or published.

Godfrey places the selection of readings within public discussions at the intersection of Black political activities, art production and reception. The artists themselves discussed the relationship of their work to broader directions in art and to the Black American community. The most contested questions throughout the collected readings are around the subject of Black Art – is there such a thing? If so, what defines it? Is there a Black aesthetic? Are Black artists directing their work at a broad art community – meaning the white population – or at the Black community? Do they have an obligation to create work that supports the struggles for political and economic justice for Black Americans? These questions transcended the visual arts and were widely discussed within the literary and theatrical communities and some of the readings reflect this.

The artists of Spiral, an early New York City group, had diverse ideas about what being a Black artist meant (they used the term “Negro” in interviews cited with Jeanne Siegel in 1966). James Yeargans suggests they should take something out of the current political events as well as draw upon a little known but deep cultural heritage, but none of the Spiral artists supported art with a goal of social uplift that would be the basis of the Black Arts movement. They explored and dismissed the idea that something about their common background characterized their work, as jazz did in music, and Romare Bearden expressed concern that he, as well as others,“had so little rapport with his own community.”

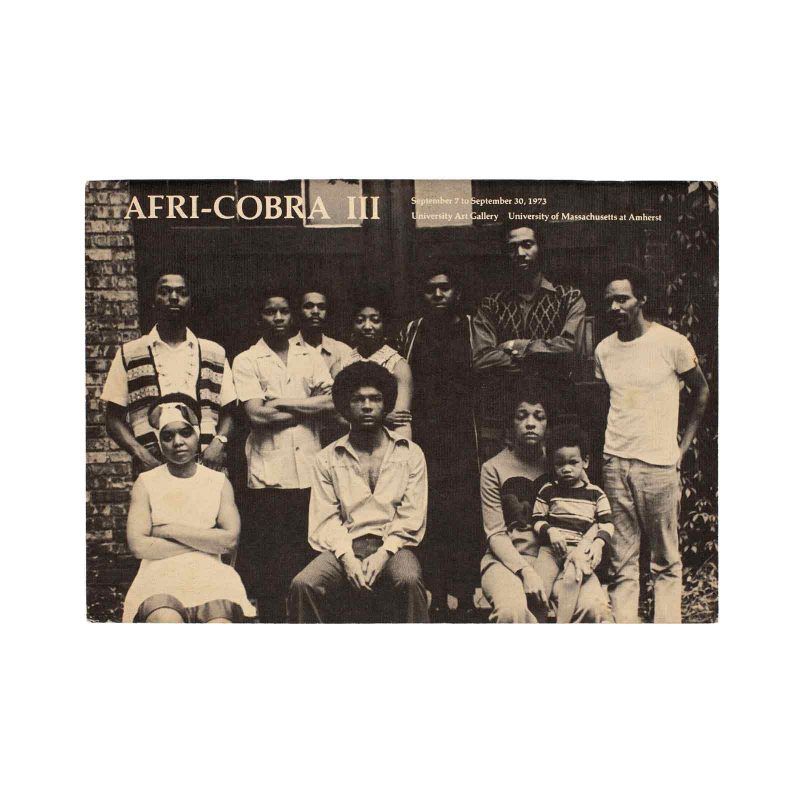

One of many valuable aspects of the selections is that they represent art communities in Los Angeles, Chicago and Boston as well as New York – a broad view which mainstream art publications ignored for a long time. And the communities are not shown to be single-minded. Chicago’s “Wall of Respect” (1967) became a national model of art directed at the Black community. It was created by a group of artists in Chicago who produced a manifesto about the qualities they employed in art intended to “enhance the spirit and vigor of culture in the Black community” with “heroic self-images and standards of beauty relevant to the Black experience in America.” Yet in 1969 when Richard Hunt, a sculptor raised, educated and working in Chicago, had a public conversation in New York with a group of his colleagues he said that “ ‘the aesthetics of Black art’ is a problem I really don’t address myself to, in either my work or my thinking.”

The readings reflect the variety of situations in which Black artists worked, exhibited, assembled, and wrote about their work and that of each other, and occasionally got together to demonstrate against institutional racism. It is notable that when white institutions exhibited their work it was usually in exhibitions devoted to Black art or single-artist exhibitions, but rarely integrated within the museums’ thematic, group exhibitions, much less their permanent collections. Things don’t look so different in 2021 for exhibitions, although there has been a lot of movement during the past couple of years in acquiring work by Black artists who had previously been ignored and some integration of museum professional staff. In the past year the major art periodicals have also discovered a range of overlooked Black American writers, and dealers have dramatically integrated their stables of artists.

The artists’ voices come through most consistently throughout the readings, even when they were written by journalists, critics, academics and others. They give a ground-level view of what it meant to be a Black artist during the 60s through 80s and the range of barriers Black Americans faced beyond the precarious conditions under which all artists worked and continue to work. This anthology along with the parallel “We Wanted a Revolution; Black Radical Women 1965-85/ A Sourcebook” (Brooklyn Museum, 2017) will provide essential information for anyone researching American art of the period.

‘The Soul of a Nation Reader; Writings by and about Black American artists 1960-1980’ (Gregory R. Miller & Co., New York: 2021) is available to purchase through the distributor, Artbook | D.A.P. or at Barnes & Noble (amongst other stores).