As a professor of art history, I am a regular museum visitor. One of my favorite institutions is the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), which adjoins the National Portrait Gallery. I regularly take my students there because the quality and diversity of the exhibitions provide excellent examples of varying media, time periods, styles, identities, and exhibition designs. They have been collecting and showing work that recognizes the diverse culture of the United States for some time. Also, they house the Luce Foundation Center which is a teaching laboratory. You can see many more works in open storage, including paintings, sculptures, and decorative objects. The Conservation lab is visible through large windows. SAAM runs the Luce Local Artist Series for performances and studio visits too. The Renwick Gallery, though not at the same location, is part of the SAAM.

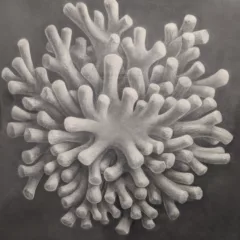

The permanent collection ranges from the colonies of New Spain and New England to contemporary art. The SAAM mounts several major thematic exhibitions per year, which brings me to my latest visit. Two recent exhibitions reflect the breadth of topics and time periods that support the museum’s claim of documenting America’s visual culture from the colonial period to today. The first, Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture, curated by Eleanor Jones Harvey explored Humboldt’s (14 September 1769 – 6 May 1859) continued impact on how we think about the natural world. He was a scientist who believed that the arts are equally important. The exhibition just ended, but there is a wealth of online materials and a rich catalogue that you can order as well.

In 1804, Humboldt spent six weeks in the United States discussing art, science, politics, and exploration with important figures including the artist Charles Wilson Peale and President Thomas Jefferson. Humboldt, who published 36 books and kept up an international correspondence, influenced our nation’s cultural identity and its relationship with the environment. He anticipated climate change. Paintings by Frederick Edwin Church and Charles Wilson Peale, among others, were included in the show. Especially interesting is the film produced for the exhibition, “Alexander von Humboldt and ‘Heart of the Andes’: An Immersive Journey,” which examines the famous Church painting and its connection to Humboldt’s ideas and observations.

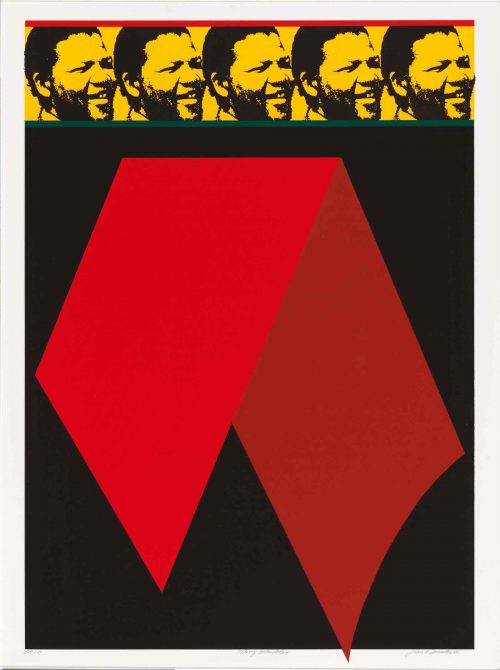

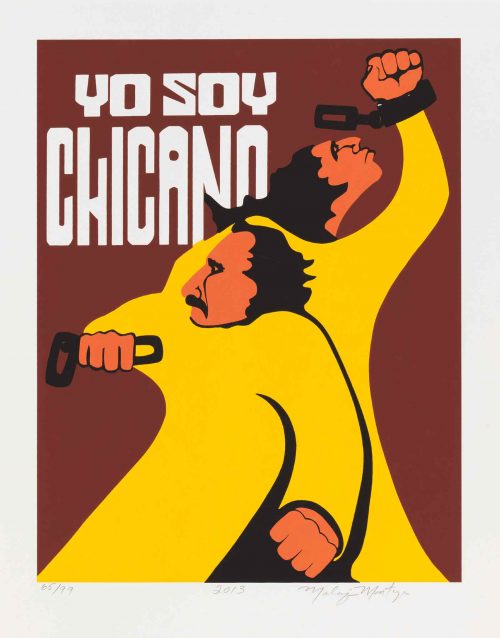

Moving from the 19th century to the 20th and 21st centuries, we enter ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, curated by E. Carmen Ramos, acting chief curator and curator of Latinx art at the SAAM with Claudia Zapata, curatorial assistant for Latinx art. Since arriving at the museum in 2010, Ramos has doubled SAAM’s Latinx collection.

The dominant medium for the show is screen printing, but other processes are also represented, including digital. The 119 prints on display are drawn from the museum’s vast and growing collection of 500 graphic works by Chicano artists. Many are poster size or larger. The museum plans on producing more exhibitions from this important collection and sharing it with other institutions as well. The subjects are overwhelmingly political, with topics that address civil rights, labor, war, immigration, feminism, and LGBTQ+ movements. The exhibition is colorful, dramatic, and, like all the major SAAM exhibitions, accompanied by rich programming and an excellent catalogue with essays by Ramos and Zapata, as well as contributions by Tatiana Reinoza, assistant professor of art history at the University of Notre Dame; and Terezita Romo, an art historian, curator, and writer. The website is good too, with links to interviews, films, and lectures. Works on paper are not on view for long periods of time due to deterioration from light. This exhibition provides a unique opportunity to look at prints that are typically in storage, and while they can be seen online, their visual impact is far greater in person, not to mention the brightly colored exhibition design around them.

The Civil Rights era was central for Mexican Americans. The term “Chicano” refers to the Chicano movement that began about 1965. It references people of Mexican descent in the United States. Originally a derogatory term, it was reclaimed as a positive image and a rejection of the concept of melting-pot assimilation. Chicana indicates women who prefer this designation while Chicanx is a contemporary and inclusive identification term. Stephanie Stebich, in her director’s foreword for the exhibition catalog, connects the past with the present, linking the art of resistance from the original Chicano movement with today’s global efforts against economic and social inequality, also accompanied by visual art.

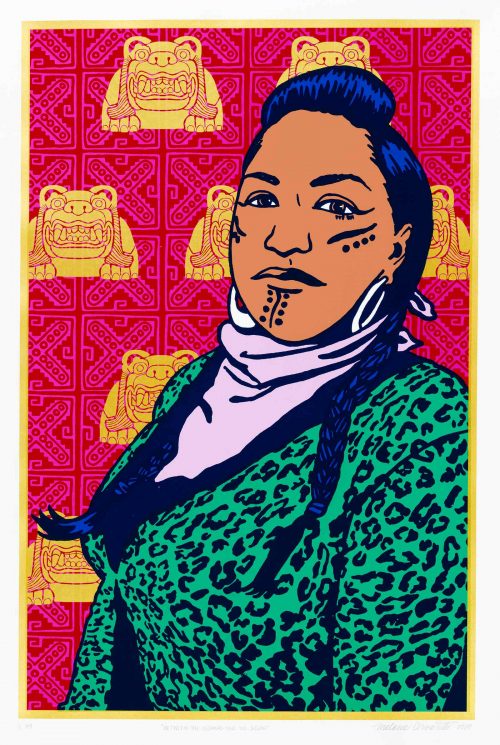

Images like “Huelga!” (1966) by Andrew Zermeño and “Tierra O Muerte” (1967) by Emanuel Martinez connect to Melanie Cervantes/Dignida Rebelde’s much later “Between the Leopard and the Jaguar” (2019).

Huelga translates to “strike.” The artist designed this poster for the United Farm Workers. Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which later merged with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) becoming the United Farm Workers (UFW) labor union. Don Sotaco, a recurring character in Zermeño’s work, calls for a strike by farm workers.

“Tierra O Muerte” translates to “land or death.” In 1967, Martinez joined the Federal Land Grant Alliance, a group based in New Mexico in the 1960s that stood up for the land rights of residents of Mexican descent who had lived in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado for centuries and had used the land communally. The treaty to end the Mexican American War, signed in 1848, guaranteed that current residents would retain their land rights after the New Mexico territory was transferred to U.S. ownership, but the treaty was not honored, and over time, many traditional shepherds lost their land to cattle ranchers and the U.S. Forest Service. The demand for return of the land is depicted here through the character of Emiliano Zapata, who was a leader of the Mexican Revolution.

A younger artist, Melanie Cervantes, created “Between the Leopard and the Jaguar” to address the traditions and strength of indigenous communities since the Conquest of the Americas by European peoples. She is a co-founder of Dignidad Rebelde, “a graphic arts collaboration that produces screen prints, political posters and multimedia projects that are grounded in Third World and indigenous movements that build people’s power to transform the conditions of fragmentation, displacement and loss of culture that result from histories of colonialism, patriarchy, genocide, and exploitation.” This intersectionality of multiple oppressions represents a contemporary point of view. Here she depicts an indigenous dancer who performs traditional dances, making commentary on the importance and continued survival of indigenous culture.

Shizu Saldamando, who is of Chicano and Asian heritage, depicts people she has met at dance clubs, music shows, and art scenes. She is interested in the youth culture of Southern California and individuals on the margins of society. For instance, In “Alice Bag” (2016) she features the musician Alice Bag, lead singer and co-founder of The Bags, a Chicana feminist first-wave punk band from Los Angeles. The image is pen on fabric, a paño art tradition typically created by Chicanos who are or have been in prison.

Similarly, Favianna Rodriguez in “Climate Woke” (2018) utilized a graffiti-like text associated with urban spaces and transgressing civic rules, to produce a digital image that presents the intersectionality of racial injustice with climate change, pointing out that low-income communities are more likely to suffer environmental harm.

From the earliest works in the show to those being made recently, the images present a vibrant, active arts community that has been and continues to be concerned with issues of economic, political, and social justice.

‘¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now‘ is on view through August 8, 2021, at the in the Smithsonian American Art Museum (8th and G Streets, NW, Washington D.C.). Entry is free to the SAAM. Next, the show will travel to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas, where it will be on view February 20, 2022 – May 8, 2022.