I’ve always hated needles. Thankfully, my second shot last April went faster than the first. I was in and out of the Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital in no time. Over a year of living in existential dread snuffed out in a matter of minutes. They said we wouldn’t be fully vaccinated for another few weeks. Still, it felt good to be (mostly) done with it. Once again outside, I decided to get an iced coffee and climb to the top of Federal Hill to chill out up there for a few. Making my way towards Starbucks, I noticed a faintly sweet smell in the air, like freshly made caramel.

After getting my drink and ascending the ziggurat-like mound, I found an empty bench facing Baltimore’s Inner Harbor and took a seat opposite the waterfront towers whose aquatic reflections swayed in the middle distance. It was a crisp, overcast April morning and the sweet smell of caramel still lingered in the air. This is one of the best views of the city; it’s the image that appears on postcards with cheesy typefaces and exclamation points: Come Visit Charm City! This is the view advertising executives and creative directors use to placate tourists who desperately need to know that Baltimore is just like any other city in the country. And, in many ways, it is. Despite its grim depiction in TV shows like The Wire, or crude pronouncements of it as a “a disgusting, rat- and rodent-infested mess,” which is how Trump described the city in 2019 while denouncing the now-late U.S. Representative Elijah Cummings, Baltimore is a fairly typical American city. Though its Rust Belt glory days are far behind it, Charm City abides.

Below me, workers were in the midst of building a new amphitheater next to Rash Field. From that height, the construction vehicles looked like toys. Baltimore was a busy little Legoland. Looking east across the harbor, I noticed that the iconic “Domino Sugars” sign that faces the Inner Harbor was gone. Or, rather, the letters and logo were missing; their supporting scaffolding remained intact. I then remembered reading somewhere that the light bulbs were being replaced with energy-efficient LED lights in anticipation of the refinery’s centennial in July. Like a light bulb in my own head, I realized the caramel smell in the air was from a fire at the Domino Sugar plant just the day before. Yet from where I stood, the facility didn’t appear damaged in any way. No signs of smoldering were in the air. Other than the letters and logo missing from the sign, everything looked the same. Had I dreamt the fire? I decided to go on a little walk to investigate. As I got closer to the plant, the sweet scent of caramel intensified.

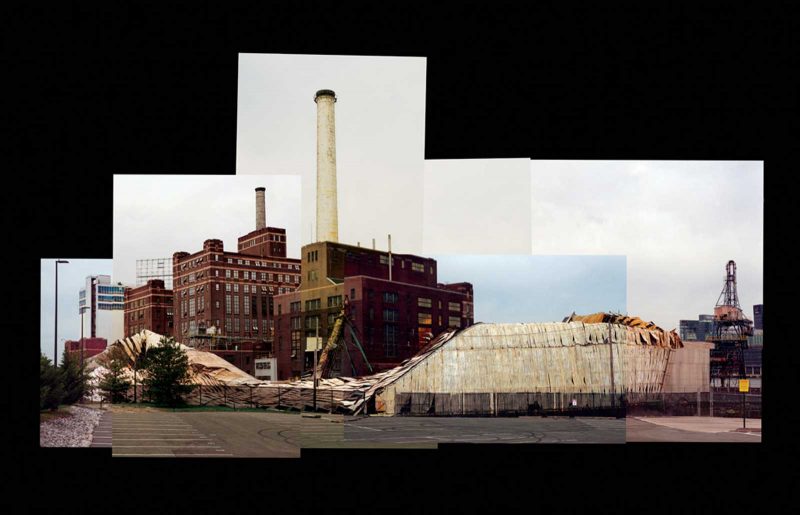

The road leading to the Domino Sugar facility in Baltimore – the tail-end of Key Highway – curves at a painstakingly long arc, creating the sensation that your point of destination recedes farther and farther into the distance as you approach it. When I finally arrived at the site, not much was going on. The vast majority of the building complex remained intact. A giant metal, bean-shaped shed lay slumped in its middle as though deflated. Small streams of smoke wafted through cracks here and there. Two shiny fire engines were positioned at either end of the site with their hoses at the ready and red lights quietly flashing in the overcast morning. I didn’t see any firefighters or other emergency workers. As I got up closer, I noticed a small group of men in neon vests and hardhats investigating the scene. They didn’t pay any attention to me, but I was still hesitant to take out my camera.

Photomontage by Dereck Stafford Mangus

A less-timid disaster tourist came up behind me and began taking copious photos. I decided it was safe to snap a few of my own. I then ventured over to the side of the facility and found an even better view next to a parking lot. There was what appeared to be a security detail parked nearby, so I chose to keep my distance. As I began my second series of shots, a man rolled up in his car and jumped out, a small camera in his hand. Based on his accent and brazenness, he seemed like a local. He swaggered past me with his cheap point-and-shoot, and made it about halfway across the lot before the men in the car ordered him via megaphone to stop. He halted his advance, took a few shots, then stomped back to his car mumbling before driving away.

. . .

Making my way south through the surrounding neighborhood, it occurred to me that the fire at the Domino Sugar plant this past April was a disaster not unlike the pandemic, in that it could have gone much worse, but could also have been avoided all together. Nobody (thankfully) died in the fire. Still, it got me thinking about disasters – big and small, global and local – and how we as a society respond to them. What if it had been worse? Who would have been most affected? The factory workers, of course. And what if the fire spread to the surrounding residential area, Locust Point, a mostly working-class neighborhood? Again, it would be the more economically disadvantaged who would endure the worst of the inferno. Which is why, when considering the ongoing emergency combating a virus that spread like wildfire across the planet, or when contemplating future calamities such as the looming global climate crisis, we need to remember all of the members of our increasingly interconnected global community. We can’t just think of ourselves.

Upon returning to Federal Hill, and the picture-perfect postcard view of Baltimore, I could still smell the sweet scent of burnt sugar wafting through the air. As I approached the American Visionary Art Museum, I looked again eastward, towards the Domino Sugar plant. It still appeared as if nothing had happened. The rectangular armature devoid of its iconic logo, suggested that Domino Sugars was on hold for now as it attends to repairs. The world as a whole seems like it’s on hold right now. Sometimes you get a second shot; and if we all work together, humanity may have its own.