When Black Lives Matter protests in Philadelphia became a regular occurrence in 2015, I created a profile photo on social media that was a text image which read, “When did Moore start accepting Black students?” I had been attending Moore College of Art & Design for less than a year and that question felt important to be asked — with both metaphorical and literal intention. It wouldn’t be for a few more years until I learned about Anna Russell Jones, who graduated from Philadelphia Design School for Women (the former name of Moore College of Art & Design) in 1925 and passed away in 1995 (a year before I was born).

Currently, the African American Museum in Philadelphia is showcasing the life and work of Jones in a two-floor exhibition titled, “Anna Russell Jones: The Art of Design.” As a little known but majorly accomplished designer, Jones is more than deserving of a comprehensive showcase. To appreciate her work is to understand the unusual circumstances under which she became a freelance designer in the early 1900’s. At this moment, there is little evidence to suggest that other Black women during this time period achieved similar levels of independent success within the field of design in Philadelphia.

This groundbreaking exhibition was curated by Huewayne Watson, a guest curator who previously focused on researching Jones while he was an Institute for Museum and Library Services fellow at AAMP. The majority of materials presented are from Jones’s personal archive, which was acquired by the museum in the early 90’s. It was Jones herself who reached out to AAMP to see if they would have interest in housing the collection that she had built for herself over a lifetime.

Jones’s other accomplishments include enlisting in the Army, thusly becoming the first African American woman from Philadelphia to do so. While serving, she produced graphic design work for the military and would go on to win numerous awards for her contributions. After returning, Jones enrolled in Howard University’s medical school as the only student studying medical illustration. Jones also designed posters promoting Black history. She became a practical nurse. After a long career, she married in her 50’s.

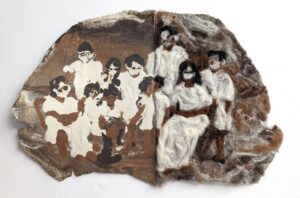

The fact that Jones is the main archivist that made her own show possible is fascinating, and noted well by the exhibition via a wall that shows some of Jones’s family photographs; it seems that archiving was a practice that she learned from her parents.

While the materials Jones managed to preserve are a mighty gift to historians and the public, “The Art of Design” lacks the curatorial contextualization needed to make full sense of what is being presented. Biographical information requires interpretation, which is a risk historians must take in order to make the past more tangible. Otherwise, the audience is forced to produce their own — and likely flawed — interpretations from the extremely limited contexts provided.

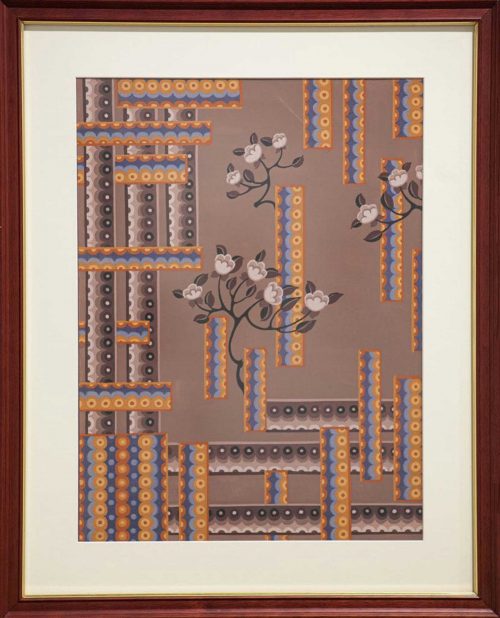

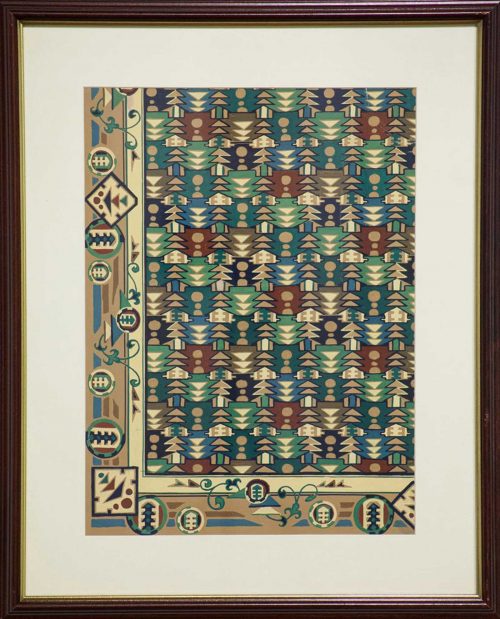

For instance, the vast majority of the exhibition is comprised of gouache paintings that Jones created as rug and carpet designer. These detailed paintings are beautiful, crafted with mathematical precision and stylized with flourishes inspired by a variety of cultures. However, little information is provided that can lead us in viewing these designs within a historical context: are these designs exceptional compared to what else was being drafted at the time? Was Jones making innovations in how she created new pieces? Was she expected to create new works daily? Weekly? Are her carpets still being used somewhere in the country?

Unfortunately, the curatorial text is muddled by jargon and only offers clear information when providing empirical data about Jones’s career. It seems as though the curatorial team behind the exhibition believed in the value of the work, but did not have the specificities needed to fully contextualize Jones’s designs. I applaud the museum for hosting the show and my hope is that their effort is a catalyst for new historical investigations into Jones; for new speculations on the reasons for her uncanny success and information on the intricate properties of her design work.

Still, “The Art of Design” is a pleasant viewing experience. To see Jones’s handiwork in person is a testament to the analog skills needed to create designs, something that viewers may not be aware of, or have never witnessed in such close detail before. Jones worked in a variety of styles and her work is aesthetically magnificent. The fact that she worked in interior design brings relevance to her compositions in a way an abstract painting may not for some viewers.

Those who would like to learn more about her should most definitely visit “The Art of Design,” closing September 12th. The show can be seen either in person at AAMP or via the comprehensive online exhibition hosted on AAMP’s website. “The Art of Design” is an impressive showcase of biographical information, complete with a short documentary directed by Nadine Patterson; the film shows Jones just a few years before her passing at age 93, telling the story of her life.

As I was visiting, I learned that it wasn’t until 1945 that Moore explicitly stated that Black students could attend. Stunningly, Jones was the only Black student to ever enroll between the school’s founding in 1848 and the change in the institution’s charter in 1945. Processing what this all means would mean analyzing race relations in Philadelphia higher education, investigating institutional practices in policy change, and comparative research on other African American women designers in the country around the same era — just to start! Our questions are important tools and the starting point for enlightening discoveries.

“Anna Russell Jones: The Art of Design,,” is on view through September 12, 2021 — both in-person at the African American Museum in Philadelphia, and as a virtual exhibition on AAMP’s website.