In his eponymous exhibition at Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, Mike Cloud presents twelve artworks that antagonize the arguments made for the relevancy of painting. Cloud’s uncouth paintings radiate pessimism; the same kind found in Afro-pessimism, a philosophical certainty of an inevitable violence towards “blackness.” Cloud paints and points towards the critical problems that arise whenever a painting is attempted to be understood.

In the curatorial text for the show, Cloud’s work is described by their unusual constructions rather than by any signified theme. However, each piece is stacked with potential meaning as Cloud places an overabundance of signifiers into each work. Viewing Mike Cloud is challenging, as viewers are asked to determine (or abandon) meaning for themselves. Should they choose to attend, and they should, audience members will be met with a stunning body of work and an impeccably installed exhibition.

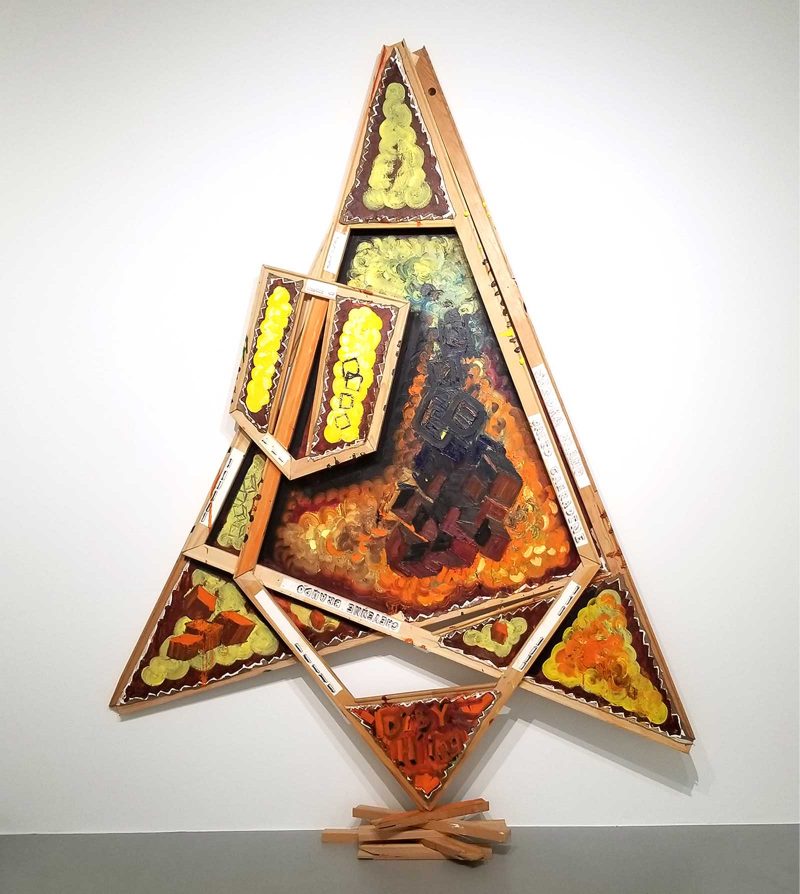

Cloud’s paintings are famously characterized by exposed stretcher bars that adhere, layer, and connect into each other and form ragged shapes. The artist often uses the thin exposed wood to paste linguistic information; clippings from gallery promotional materials, strips of Whole Foods paper bags, names written in juvenile block lettering onto sketchbook paper. In the open spaces, thick strokes of saturated oil paint are applied with expressionistic conviction.

Other works include a series in which children’s clothing is stitched onto contoured canvas and linen. In a manner that resembles graffiti, Cloud places a few sparse paint marks on top of the material. The largest piece in the gallery, “Red Triangle Geometric Quilt,” is a collection of little boy t-shirts and pants that have been split open and laid across a massive web of stretcher bars. The splayed imagery is startling and it is unnerving.

Does this piece represent disastrous violence against children, whose bodies are implicated by the presence of their strewn about clothing? Must discarded children’s clothing be seen as violent, when there are millions of tons of it in landfills all over the world? Then there is the question of the clothing selection itself.

“Rabbit Quilt” is a smaller iteration, featuring only a Happy Bunny tank top and pirate Spongebob pajama pants, complete with repeating skull and crossbones. As someone who was still a kid in 2008, the year “Rabbit Quilt” was created, I immediately recognized this as the outfit of the edgiest girl at the 2nd grade sleepover. I would be stunned if this specific characterization was intentional. There is a form painted across the clothing that is reminiscent of a running rabbit, which I initially saw as a wild canine.

Certainly there are moments where violence may be implied, but there are plenty of others where it is outright depicted. There are three paintings that feature the names of six individuals, all of whom died by way of hanging and whose deaths were extensively reported by the media; Jang Ja-yeon, Robin Williams, David Carradine, Otávio Jordão da Silva, Cheyenne Brando, and Sandra Bland.

Two of these works, “F of J” and “S of B” are quite bodily in form. They both rest on a stack of wood as if they are being burned at the stake. The red and orange paint that appears at the bottom of each work compliments this reference. “F of J” also is suspended by a small pink belt, which allows it to lean to the right in a pose of perpetual tension.

“Cantanheade Portrait” is more straightforward in its gruesome intention. This abstracted portrait, the first piece in the gallery, represents a particularly violent death and does so with a guileless approach. The middle of the painting is cracked open. Two sets of square stretcher bars are laid on top of each other and the corners of the painting symbolize various parts of the face; one says “eye,” the corner on the opposite side says, “tooth” and the one next to it reads, “lip.”

The next work in the space, “Shopping List Greener Pastures” is curious, due to the fact Cloud has arranged his stretcher bars to form two Stars of David. Between these two forms, there is a trapezoidal panel that depicts a cartoonish mound of earth with a palm tree and two pyramids. In the middle of each Star, Cloud writes a series of antagonizations; “RED VS GREEN APPLES,” “YELLOW VS RED PEPPERS,” “GREEN VS GREENER PASTURES,” “YELLOW VS INDIAN CORN.”

There is a looming question of earnestness in “Shopping List Greener Pastures.” Does Cloud himself view these dichotomies as legitimate or does his display of them point towards their foolishness? Does his invocation of the Star of David represent a spiritual statement or is it folly? While Cloud’s intentionally ambiguous approach to subject matter is clearly indicated in the curation of his show, using such powerful symbolism in (never ending) times of anti-Semitic violence in America should be considered with skepticism.

The way paintings have been historically and critically understood is based in fundamental delusions of clarity. To receive critical meaning from an artwork requires knowledge of a system of communication that is based in colonization and profiteering. So then, are there other ways we can look at paintings? The works in “Mike Cloud” allude to the body, more often than not in situations of destruction. Transformation requires the acceptance of death and the desire to see what else is possible because of it, not in spite of it.

“Mike Cloud” is on view through Oct. 2, 2021, at Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, 333 S Broad St, Philadelphia 19107