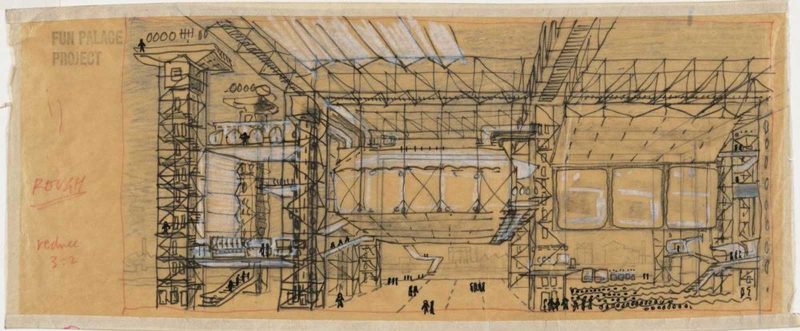

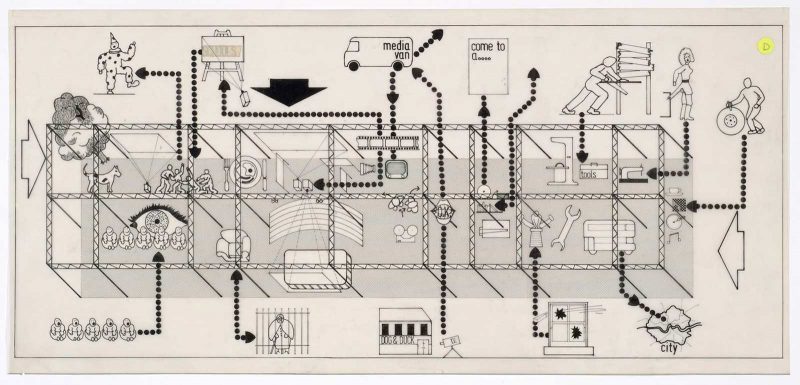

1959–1961. Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

Reflections/ Flowerings/and Layouts

There’s no denying that this past year has been extremely challenging for us all. From social isolation to the violent spasms within our political, environmental, and social spheres, this drastic flux has especially impacted our experience of physical space, both inside and out. We speculate on new futures for collective action, particularly human-centered planning that provides us with the tools to re-remix, re-make, and re-imagine our urban spaces. This collaboration is the beginning of what we hope inspires an ongoing and open dialog with the larger community.

Changing the use of Public and Private Space – Multitasking and Inclusion

Mandy Palasik: During the height of the Covid lockdown, streets were apocalyptic scenes – ghost towns. Seemingly overnight, upon the news of George Floyd’s murder, barren streets were ringing with democratic voices demanding justice. Streets aren’t just a space for cars, they are a public domain where people are to be heard. Where impromptu al fresco dining sustains cherished local business and block parties unite communities.

Our homes have become multi-functional spaces of refuge, education, creativity, and productivity. Kitchen tables doubled as desks. Bedrooms became classrooms. Although the inclusion of multi-functional programs has long existed, we have been challenged to evolve from the conventions of single use and to think about space as inherently flexible, inclusive, and temporal. Although there is a dire desire to “return to normal,” It would be a huge missed opportunity if we failed to assess and redefine spatial conventions based on this past year, and counting.

Kemuel Benyehudah: Mandy, I agree… a return to normal should not exclude more multidimensional remixes of public and commercial spaces. If we’ve managed to re-imagine our homes by turning them into remote office spaces and classrooms, then why can’t we do the same with public ones?

Now more than ever, redesigning our relationships with space is crucial. Our work and commercial spheres are severely strained and will need serious re-thinking if they are to work for more people; otherwise, these spaces will lose their attractiveness. During the pandemic, workers discovered the health benefits from working less, which has made returning to the old conditions undesirable for many. Unfortunately, the corporate and political class is trying to stigmatize protestors by saying stimulus checks have made them lazy.

However, when zooming in closer we see that our current economic system has been failing people way before the pandemic, and that the pandemic crisis only brought those realities into sharper focus. The end result has been a larger cultural divide regarding work and well being. Unfortunately, those in power have refused to accept these realities and refuse to radically improve working conditions. Therefore, increasing numbers of people are choosing to drop out of the economy and seek out alternatives. Critical race theory and socialism are being conveniently blamed for economic and education troubles, rather than the illogical constructs of capitalism and racism.

Learning from capitalism, utopian experiments and COVID

Kem: On one hand we’ve been led to believe that capitalism has made all of our lives better; but on the other hand I’m consistently witnessing widespread poverty, gentrification, and instability in people’s lives. Despite the failures we can all see around us, capitalism is still championed as the great equalizer for historically marginalized communities. Yet, the disaggregated data doesn’t quite support the market gospel. For example, there are less Black businesses and more incarcerated Black men since President Nixon’s day. So, when looking at the data, it’s hard to argue that capitalism is working for Black communities. I know some may argue, more nuanced perspectives are necessary before we wholesale indict a whole system. But, if some groups keep finding themselves on the short end of the stick, wouldn’t you too think it might be time to try something different? Is that so bad? If it is bad, then for whom and why? Ask yourself for a minute, what if more capitalism is not the solution for lifting more boats… What if more re-distributive interventions are what is needed to build more healthy communities? Unfortunately, many in the planning and development community are not thinking about community and are thinking about self interests over people.

Davarian L. Baldwin points out, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower, that Black people are often objectified as obstacles in the way of development. The Black community’s contentious relationship with development is emblematic of the larger issues generated by late stage capitalism. On one hand the capitalists developers receive enormous profits, while on the other Black and Brown people suffer vast human tragedies, displacement, and minimum gains. Therefore, I’m not one to cite one and a half years of stimulus checks, unemployment support, and rental assistance as radical reforms. Instead, we’ve just feigned ignorance of the truth and decided to live with the shadows in the caves.

Mandy: Well said Kem, your point on the inability of Black capitalism to eradicate systemic inequity further emphasizes the ongoing failures of planning politics and the dire need for a multi-layered approach. Although business ownership and direct investment opportunities such as Buy The Block provide a “seat at the table”, these initiatives alone are not enough to remedy the ingrained failures of American policy and planning. Far too often, the community’s concerns are overpowered by the forces of capitalism, further contributing to displacement and gentrification. Likewise, many planning and redevelopment projects utilize community engagement tactics as just a formality, a box to check off, with little integration of feedback.

Community-led organizations serve as a vital resource to facilitate inclusive participation, albeit on a small scale with often limited resources. An example that comes to mind is Open Architecture Collaborative, a volunteer-run non-profit organization that offers pro-bono design services “ to inspire ownership and civic engagement in traditionally marginalized communities.” Supporting cross collaboration at the local and agency level, The Los Angeles chapter (OACLA) has partnered with the community on projects such as Covid-safe signage, outdoor dining space for minority-owned businesses, and marketing material to support community center renovations. They are currently supporting the brick and mortar home of Suprmarkt, a Black woman owned initiative to bring affordable and healthy food options to the food desert of South LA. Projects like these really do take a village to realize and are so essential in their overreaching impact.

Pragmatically what we can take from examples such as OACLA is to equip communities, especially those historically underrepresented, with the infrastructures and resources to fulfill their specific needs – with support, not intervention. Acknowledging this takes time, money, and trust – the challenge is, how can we successfully implement this infrastructure at a universal scale? How can we better fund and equip nonprofits and community organizations to further their reach?

Technology for all is good but technology should not replace real space

Mandy: It’s no surprise that these spatial shifts have been heavily influenced by the use of technology, society’s textbook definition of “the future.” Daily commutes in gridlocked traffic have been exchanged for cyberspace networks, while cubicle enclosures have been reduced to Zoom screens. Where will this take us? I’m reminded of the work of the late Cedric Price, a visionary British architect that celebrated the ephemeral and uncertain, and his 1960s proposal for Fun Palace. Slated for East London’s working-class industrial neighborhood, Fun Palace was not intended as an enclosed building with a prescribed function, but an open infrastructure (redundant power station grid) that gave the community autonomy through the use of plug and play technology. The notable concept of Price’s plan was an adaptable architecture that supported the community in creating their own microcosm that evolved with collective needs. The marketing poster read “Choose what you want to do or watch someone else doing it. Learn how to handle paint, tools, babies, machinery, or just listen to your favourite tune…Try starting a riot or beginning a painting.” When the architecture no longer met its purpose, it was to be destroyed.

Price’s radical proposition (open screen cinemas, moving catwalks, artificial clouds to protect from the elements – remember this was the 1960s), was inspired by the desire for social reformation in the context of conservative post-war Britain. He was joined in this thinking by avant-garde colleagues such as Archigram and Superstudio, who shared a neo-futurist vision inspired by technology and a science fiction aesthetic where individuals and the spaces they inhabited were freed from the grasps of political and spatial constraints. We have experienced a parallel mindset in the democratic appropriation of urban spaces in the form of grassroots, guerilla, and tactical urbanism movements such as parklets and pop-ups.

Kem: Mandy, of course some will argue that these grassroots movements might be only cosmetic, especially when considering that past movements were co-opted and failed to bring about system wide change for all. Nevertheless, despite their shortcomings, I believe movements like Superstudio offer templates which could better inform us today. For one, architecture is indeed meaningless unless it’s integrated with sustainability and human needs. The earth is burning and most people are still pretending like it’s not happening or that it will ever affect them. Instead, I hope today’s generations will learn from Superstudio and others, and realize that technology alone can’t lead us to the utopias that we imagine. If we’re going to realize and execute real change, then it may be time to demolish some systems and build new ones from the ground up!

Demolition vs Reuse, and Grounds up Solutions

Mandy: Kem, you mention our increasing dependence on online commerce, social platforms, and the migration to remote work. This brings up a great question on the relevancy of former physical spaces. With the surplus of vacant offices, storefronts, restaurants, etc. resulting from the pandemic, it’s clear that our focus on mono-functional typologies isn’t efficient. Programming space is a balancing act. As Liz Diller noted to me in her interview on The Shed in New York, “Architecture can hardly keep up… It’s out of pace for the culture that is changing so fast.” Designing for flexibility is key. How do we design and plan for a rapid changing society where needs, demographics, cultures, and forms of productivity are constantly evolving? Do we become a society of plug and play building types- or a city of empty sheds?

The neo-futuristic proposals of Cedric Price and his contemporaries resonate with the socio-political climate we are dwelling in (aside from the suggested Jetsonian architectural aesthetic). What these propositions suggest is a malleable and temporary infrastructure that empowers democratic agency of space, one that welcomes and reflects the universal values and cultures of the greater community.

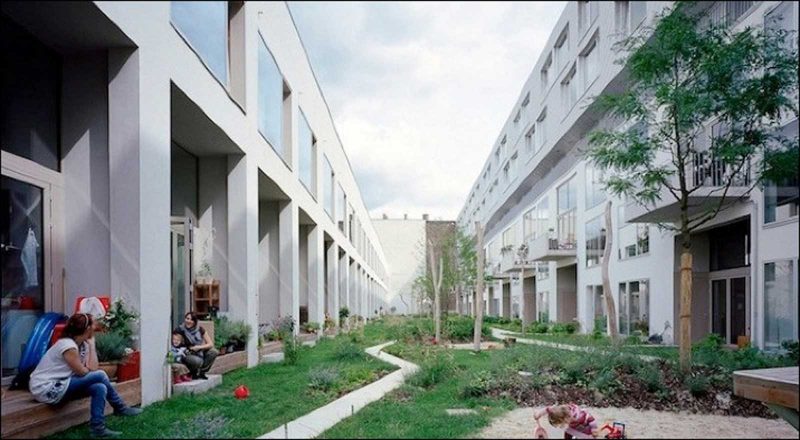

Contrary to the ephemeral concepts of Cedric Price is the work of this year’s Pritzker Prize-winning duo – French architects Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal. Their practice is rooted in sustainable principles with the motto “Never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform and reuse!”. Lacaton and Vassal consider demolition an act of violence, a form of social injustice. This is a sentiment many of us relate to when treasures like the legendary homes of Dox Thrash and Cab Calloway were put on the chopping block to be replaced by profit-driven shiny structures. We can’t help but grieve the physical loss of these culturally significant collective memories. As the historic narrative goes, Capitalist greed backed by privilege once again wins agency over the collective voice of the community.

The physical nature of space is just one part in a complex equation of urbanity that will always be in flux. This past year has reminded us that we must shift our priorities to the intangible components that work in tandem with the physical – equity, sustainability, health, wellness, etc..

Kem: Yes! Equity, sustainability, health and wellness are all vital elements we must prioritize in the planning profession’s future. Black urbanists collectives such as BlackSpace are already advocating for more democratic participation, in particularly from Black communities who have been historically marginalized by the planning profession. BlackSpace recognizes that preservation of culture, heritage, and identity, are all important indicators for measuring the well being and health of a community. In contrast, racial covenants and redlining acted as social dividers which kept Black communities segregated from economic opportunity. Today, gentrification is pushing out many native Black people from their neighborhoods due to rising rents, higher property taxes, and just plain ole land speculation. Black Space and other innovative institutions such as The Black Quantum Futurism Collective are responding to these long standing issues with speculative imagination; however, there remain concerns if these initiatives will be enough to shield Black communities from future land grabs. Due to these precarious situations, some are arguing for increased personal agency outside of the traditional pathways. However, there is still no consensus on what this might look like across different spaces.

Agency is important, but whose agency? And what about communities/communes?

Mandy: Although the thought of a one-size fits all spatial approach may seem utopian, the gist of that proposition is, let the people own, envision, and plan their future. As architects and planners, we are taught foundations of a white-male dominated industry. Our generation is tirelessly striving to remedy the negative impacts of redlining, to restore access and resources to marginalized communities, and to solve the overwhelming affordable housing crisis. Undoing decades of faulty planning is no small feat – especially when combative politics are at play.

The failures of government, top down, planning projects such as Pruitt-Igoe, speak for themselves. These were inferred shelter interventions, not a collaborative partnership that served to represent the needs of the people. On the opposite end of the spectrum, we see the bottom up, grass-roots initiatives that represent the voices and needs of a community but more than often lack sustained resources. I’ve always been intrigued by Berlin’s self-initiated collective housing models, also known as baugruppen. Perhaps it’s because the idea is such a contrast to the privatized American Dream. Individuals pull their resources to create their own communities, and it’s not just limited to financial resources. This concept of collective living is often stigmatized as a hippie commune, but it’s far more sophisticated in structure and scale. Top down support, such as land trusts, where agency owned land is leased at a low fee, creates a viable foundation for rent stabilization and/or lowered construction costs.

In order for affordable development to be sustainable on a widespread scale, there needs to be a shared goal and collaborative support from both citizens and agency/government leadership. Our wavering political turnover makes it extremely difficult to carry out long-term initiatives aimed towards social reform.

Kem: Mandy, I love how you mentioned how space reflects our values and level of respect for other cultures. It made me pause and take a step back to ponder how difficult these solutions will be to achieve when considering private property. Rinaldo Walcott writes in his book On Property that it will be difficult to solve our racial problems unless we change our fraught relationship to private property. Walcott argues that if Black people are to have a less violent relationship with policing, private property should be abolished in favor of community living. Walcott says, collective ownership brings about a more humane form of morality and ethics than one where public property is heavily policed. Of course there will be opponents who will cite the crime and violence in some communities as symptomatic of some deficiency in moral character. However, when looking at the work of Julius Wilson, we learn urban communities were disinvested by corporate America. Therefore, the unequal results we see in our American cities are far less symptomatic of failings in moral character, rather they’re emblematic of our lack of commitment to building thriving multiracial communities, especially those with large numbers of people with African descent.

What will be the future of space?: imaginings and remixes

Mandy: Architects and planners have dreamed up the idea of a utopian city for centuries – from the mobile kit-of-parts instant cities of Archigram to the overtly symmetrical grid of shiny glass towers and super highways of Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse (Radiant City). These one-size-fits all visions (led by white men) fail to address the complexities and evolving needs of diverse communities at the heart of our urban epicenters.

I go back to Cedric Price’s notion of the “anti-building” not as a grand-gesture solution, but as a proposed infrastructure to create a localized platform for democratic use and flexible programming. Could we swap out some of the vacant buildings that are infiltrating our communities with similar versions of “Fun Palaces” – where ideas, resources, and conversations are openly shared?

The closest form of Price’s democratic concept we have in our privatized society is public parks. As this past year has put into perspective, we value our beloved parks as forms of social arenas where connection to nature and wellbeing is restored. Although intended as a free space where everyone is welcome, freedom within public parks is not necessarily experienced with equal privilege when it comes to race, sexual orientation, economic status, disability, etc. Additionally, discriminatory planning has historically limited access to park amenities in low-income communities, along with the required resources to maintain health and safety.

Perhaps we could open up our backyards, lobbies, auditoriums, or alleyways to welcome community-led events and programs as temporary Fun Palaces. The UK-based not-for-profit Fun Palaces has taken on this concept as a form of social activism, creating a network of ambassadors to encourage and support “local people to co-create their own cultural and community events…sharing and celebrating the genius in everyone.” Could the solution for more democratic agency be as simple as reconnecting with our neighbors to collectively create the communities we desire? As the late Cedric Price suggests, perhaps it’s not a designated space that is needed, but the socio-cultural programming of the “anti-building” that brings us together in both conventional and unconventional spaces.

Courtesy Art Lab Fort Collins.

Kem: Your mentioning of Price’s antibuilding made me wonder what if the answers are already located in our available built spaces? And if so, what can we learn from intersecting them with the phenomenal conceptual artist, Lucy Lippard. Lippard said, for her, the idea was more important than the actual work of art. Inspired by Lippard, I’m wondering if we should be thinking more about remixing our existing urban spaces? Perhaps sampling various architectural models, living arrangements, and histories could emancipate us from old paradigms and thinking? Perhaps remixing space as we’ve done with our homes during the pandemic offers lessons for other spaces?

One example of this notion is a Black owned gallery out in Pittsburgh. Co-owners, Nicky Jo and Cynthia Kenderson, founded BlaQkHouse in downtown Pittsburgh to provide Black artists with a space to share and sell their arts. According to Kenderson, “their cultural work is connected to a larger tradition of Black artistic production which can be traced back to the historic Black Hill District.” Kenderson pointed out to me while talking with her on the roof of the gallery, that the Hill was only a few miles away from downtown Pittsburgh. Although the golden era of Jazz has since passed, Kenderson and Jo are pulling from this rich history to remix downtown Pittsburgh for Black artists. Despite the city’s difficult history, these talented visionaries are reminding us of the value of reimagining space. Perhaps building small utopias like this are the small steps needed to realize a sea change in our cities’s futures?