Peter Williams, who died in August, was an amazing artist and a powerful personality whose wisdom and humor affected the many people who knew him. Peter made those who he taught or with whom he worked feel like a close friend. I curated his work twice, once in 2007 at the Delaware Center for the Contemporary Arts (now the Delaware Contemporary) in a show entitled Baghdad and Other Unfinished Business, and then again in 2017 in a two-person exhibition Dark Humor: Joyce J. Scott and Peter Williams at Towson University’s Center for the Arts Gallery. We published a catalog for that exhibition with essays by Tiffany E. Barber and Nikki A. Greene as well as me.

Through a dramatic style of exaggerated figures, abstract design, and intense color palette, Peter addressed police brutality, inaccurate historical records, slavery, inequality, and oppression. There were often autobiographical elements and self-portraits within his complex compositions. In my discussions with Peter, he told me about his childhood fascination with comic books, especially the “Fantastic Four,” “Silver Surfer,” and “Sargent Rock.” He also, like so many children of the 50s and 60s, enjoyed television. He turned next to books by authors such as James Baldwin and Chester Hines. Peter also described a Sunday family ritual of reading five different papers, among them the “New York Daily News,” the “New York Tribune” and the “New York Times”, including the comic strips. These interests, combined with his later introduction to Blaxploitation films, his European travels, and his formal training, contributed to the development of a unique artistic voice.

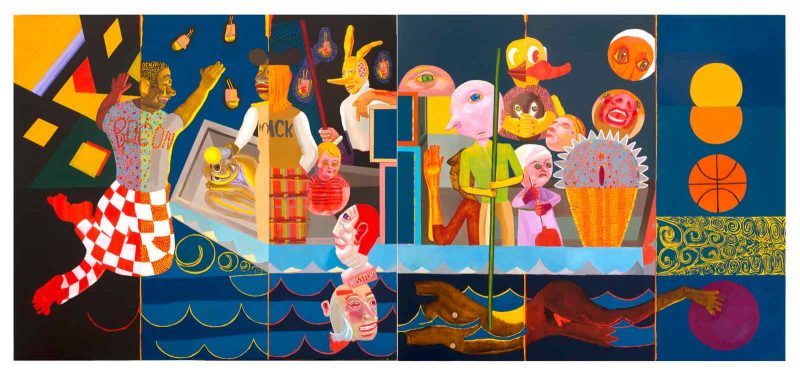

While the DCCA 2007 exhibition referred to the then United States international engagement, it was his show with us at Towson that concentrated specifically on the Black body. Peter did this through paintings such as “Nyack,” which addressed both his own life and the history of the slave trade. The painting is based on a well-known work by the American/British artist John Singleton Copley, “Watson and the Shark” (1778), originally titled “A boy attacked by a shark.” In his version, Peter completely inverts the Copley painting, transforming the boy, Brook Watson, into a Black male figure with a part of one leg ripped from his body, suggesting Peter’s own missing leg, which he lost as a young man in a terrible car accident. In the painting, he swims in the harbor/river toward two floating heads of white men, one of whom displays the label: “hisstory”[sic], suggesting the adage, “History is written by the victors.” Nyack, NY, where Peter grew up, played important roles in both the international slave trade and later, the underground railroad.

“Shipwrecked, Gillgan’s Island” (2013), addresses a similar topic. This large work takes advantage of the 60s sitcom, “Gilligan’s Island,” with a highly recognizable theme song that begins: “Just sit right back and you’ll hear a tale, a tale of a fateful trip, that started from this tropic port, aboard this tiny ship. . .” Here, the artist presents a fateful trip from a tropical port, but now it is the story of Middle Passage.

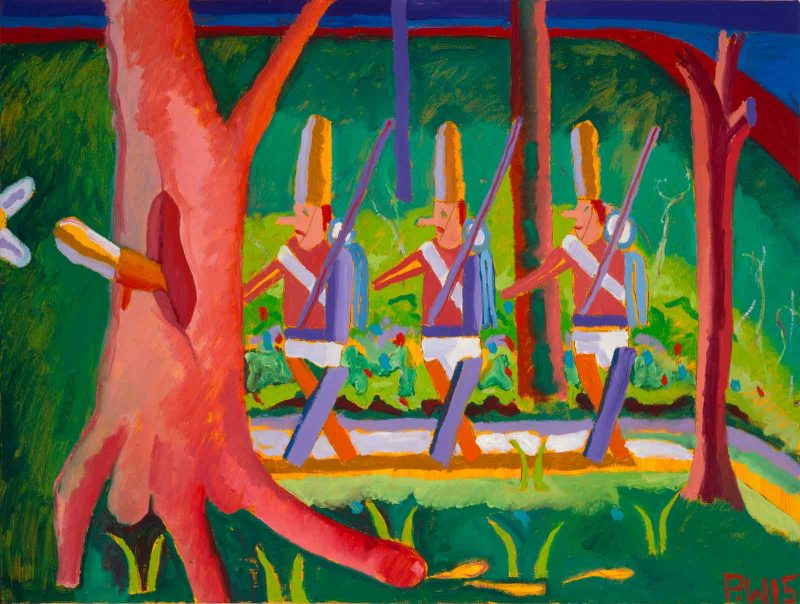

Some of the work exhibited in 2017 was impacted by Peter’s 2016 Joan Mitchel Fellowship in New Orleans, where he researched and then depicted a narrative of slave rebellions. “A Long Way Home,” is a series of seven, 18 x 26” paintings about the Haitians who were part of the colonial American/French forces to take back the city of Savannah, Georgia from the British in 1779. Black Haitian soldiers, promised future American support for their own revolution, fought alongside French white soldiers to “free” white slave owners from British tyranny. America broke its promise, but the Haitian Revolution inspired later antislavery movements.

“For a Time I Slept in the Master’s House,” addresses the 1811 New Orleans revolt by the enslaved. It is dominated by a huge, perspiring, white male head with pimples out of which Black bodies emerge. Rebellion, the worst fear of the white slave owners, is realized. The artist also depicted a foot and head, indications of the torture of the rebelling slaves, their limbs and heads chopped off, warning against any future insurrection. Williams saw this work too as a metaphor for slavery’s control of the male Black body.

Peter made paintings relevant to his life and times. We exhibited his series on the topic of the death of Michael Brown, the unarmed Black teenager shot and killed on Aug. 9, 2014, by a white police officer, in Ferguson, Mo., a suburb of St. Louis. “Da Ferguson News” and “Dis Ferguston,” both created soon after Brown’s death, recall the artist’s early interest in comic books and especially, newspaper cartoons. They echo 1960s and 70s German newspapers with their bold, red headlines. In them, Peter overtly addressed the Klu Klux Klan, police racism, and what it means to be a Black male body. Years later he returned to this topic in his paintings about the death of George Floyd.

I loved working with Peter. His affection for intense colors and abstract patterns was close to my heart. I found our talks lively and engaging. They were both personal and political. And his loss is both personal and political; I will not be alone in missing him and his biting observations. Peter was a generous person in all ways—with friendship, knowledge, and his work. He felt very strongly that his art must be a commentary on his place in the world as a Black man, which might take the form of looking back to history or to addressing how that history has affected contemporary issues. Towson University was privileged to present Peter Williams’s work.