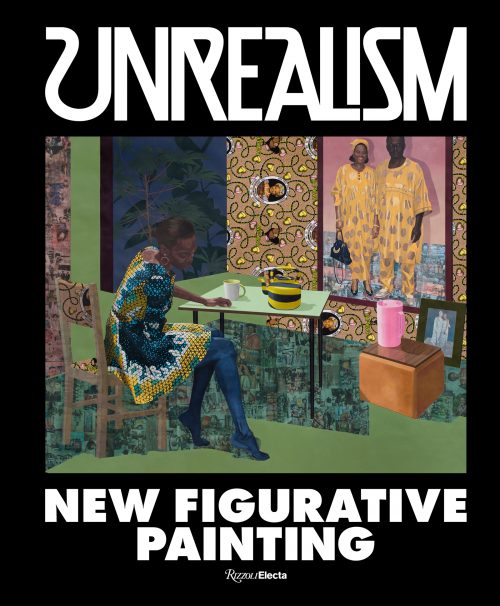

Jeffrey Deitch, “Unrealism: New Figurative Painting” (2019)

Interested in recent painting and wondering what’s out there? Trying to understand what makes new art about old subjects current? This handsomely-produced book will appeal to readers who have spent a lot of time in galleries recently as well as those who are just beginning to look. The images alone will provide a good introduction to a very broad range of approaches to the human figure by twenty-six international painters, most of whom were born in the 1980s and 1990s, and dozens of their predecessors proposed as their artistic ancestors. Jeffrey Deitch notes that women of color have been in the forefront of this revised figuration. The selection is hardly restricted to faithfully-realistic representation, and in a handful of cases I had to struggle to find the figures. The artists have been influenced by comic books, animated cartoons, movies, advertising and web games, photography and collage as well as painting traditions, with an emphasis on Symbolism, Expressionism and Surrealism.

The book is in two parts. The second, larger section contains full-page discussions of each artist and several, full-page illustrations, which gives a significantly better idea of the artist’s production than many such surveys with a single image per artist. The book begins with an article by Alison M. Gingeras, “Wrong Figures: An alt history of Figurative Painting,” which discusses the rejection of figurative traditions as early as the Eighteenth Century then traces an anti-canonical history of twentieth-century art along the line of late Picabia – Bernard Buffet – Balthus – William Copley – Joan Semmel. Jeffrey Deitch assembles more than eighty illustrations as his own “Counter History of Figuration“ from Florine Stettheimer to Cao Fei, and Johanna Fateman discusses the history of viewing the canonical from a different position and traditions taken up by artists who were previously excluded. Short biographies of artists and authors are provided at the end of the book, which may encourage some readers to create their own counter-histories, or ask whether art ever developed in such a linear manner.

Jeffrey Deitch, “Unrealism: New Figurative Painting” (Rizzoli/Electa, New York: 2019) ISBN 978-0-8478-6242-9. Rizzoli | Barnes & Noble

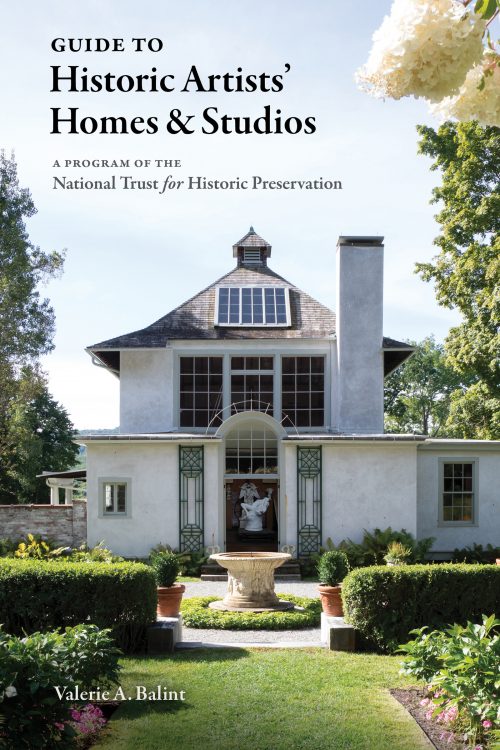

Valerie A. Balint “Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios” (2020)

Visiting the home and/or studio of an artist gives an intimate view of the atmosphere in which artwork was created, and it’s an acceptable form of voyeurism. Gustave Moreau’s studio in Paris is clearly that of a highly successful artist, based on its scale alone. The studios within homes of Frederic, Lord Leighton in London and Hans von Stuck in Munich were intended to impress patrons with the artists’ ability to create fantastical environments – what we’d now call branding. And Donald Judd’s living and working spaces in both New York City and Marfa, Texas reveal the extent to which Judd fashioned his own spaces in order to do his best work.

American artists’ homes and studios open to the public used to be a rarity; I’ve only visited Frederic Church’s, Donald Judd’s and the studio of Jackson Pollock. But the possibilities have changed over the past few decades. There is now an association of these sites, which number forty-four, and this newly-produced guidebook is perfect for art-lovers planning domestic travel. Valerie A. Balint has written several engaging and informative pages on each, which are all handsomely-illustrated, particularly for a publication that bills itself as a guidebook, making it attractive for armchair travelers who may never visit many of the actual properties.

While Georgia O’Keeffe’s house and studio at Abiquiú, New Mexico has been widely-published, I had not heard of the one-room cottage in Huntington, Long Island where Arthur Dove and his wife, Helen Torr, both lived and worked during their last years. Three towns on the waterfront in Connecticut were sites of artists’ summer communities in the Nineteenth Century: Julian Alden Weir and his son-in-law, Mahonri Mackintosh Young, had studios at Weir Farm in Wilton where artists were guests, while boarding houses in Cos Cob and Old Lyme were regularly frequented by groups of artists from New York. Visiting the three would make a good trip, and I’m inspired to plan one myself.

Valerie A. Balint “Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios” (Princeton Architectural Press, New York: 2020) ISBN 978-1-61689-773-4. Princeton Architectural Press | Barnes & Noble

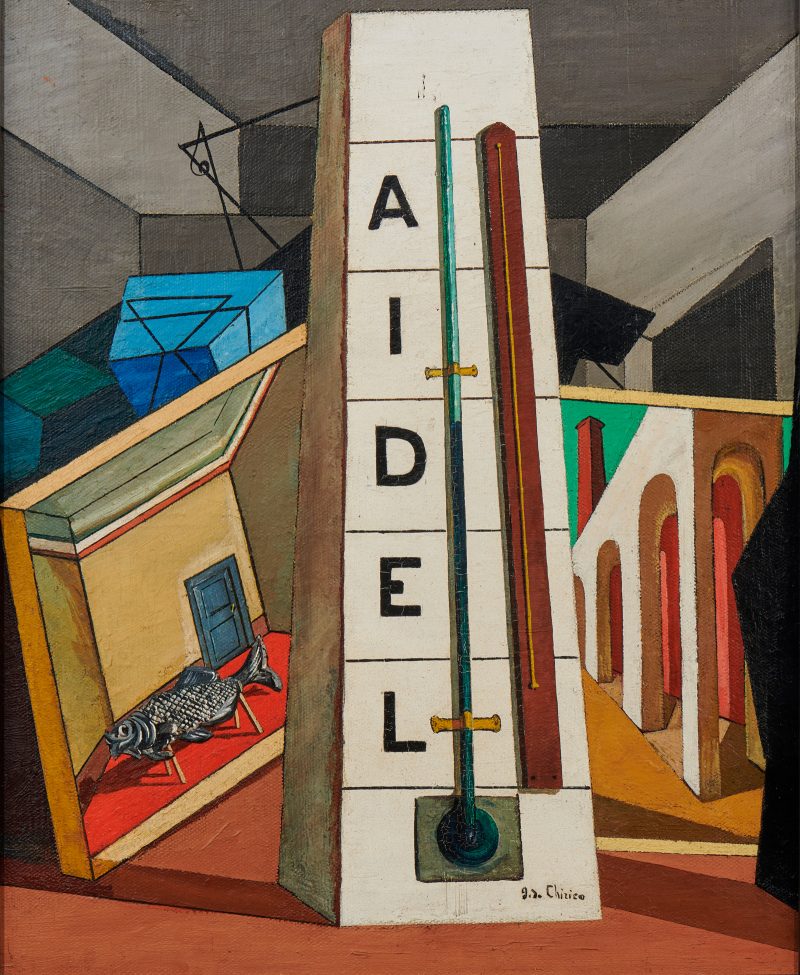

Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale, “Surrealism Beyond Borders”

This volume will be expansive and enlightening for anyone interested in twentieth century art, no matter how knowledgeable about Surrealism. While the movement’s loudest polemicists were in Paris in the years after World War I, it’s central tenets of imagination freed from reason, art free from government interference, and collective activity have retained the interest of international artists up to the present. This is a catalogue to an exhibition organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) where it is currently on view through January 30, 2022. Produced to the MMA’s usual high standards, it has several pages of text by the curators and forty-five international scholars as well as more than three hundred full-color illustrations. The artworks cover such a breadth that I doubt all of them were previously familiar to any of those authors or the curators.

The artist Takenaka Kyūshichi wrote in a Japanese journal: “True Surrealism cannot follow André Breton’s authority. The faddish kind of ‘Surrealism’ starts from Breton and never goes beyond Breton.” The two editors have rejected Surrealism’s canonical story, and rather than emphasizing chronological primacy or attempting to assign the Surrealist label more broadly, they emphasize an international exchange of ideas, conducted via art and artists’ travel and through publications, which included artists who would not have considered themselves Surrealists but accepted some of its premises. This makes the exhibition and catalog a significant model for other studies of international modernism, based upon the idea that art’s greatest significance is in its relationship to its originating culture, and that from earliest times artists have adapted ideas from elsewhere and interpreted or mis-interpreted them for their own purposes. The issue of art centers versus periphery ignores the local embeddedness of art production. The emphasis on the political grounding of Surrealist art and its consistent stance in opposing authoritarianism and colonialism is particularly interesting, and something that requires knowledge of each local situation to appreciate.

The Afro-Brazilian artist, Octávio Araújo studied in the Soviet Union where he was introduced to Surrealism by dissident artists who, like him, rejected Soviet realism. Araújo thought that only art and science, both of which Surrealism embraced, could enable Brazil to face the violence of its racial past and move to a more just society. The Turkish intellectual and calligrapher, İsmail Hakkı Baltacıoğlu, thought the combination of calligraphy, Sufism and Surrealism enabled artists of the former Ottoman Empire to deal with new ethnic-national goals. The Chicago Surrealist group were involved along with Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in protests during the 1968 Democratic National Convention and protested the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition “Dada, Surrealism and Their Heritage,” which was shown at the Art Institute of Chicago, because it presented Surrealism as a purely aesthetic movement uninvolved in politics and a movement only of the past.

Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale, “Surrealism Beyond Borders, ” (Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press, New York and New Haven: 2021) ISBN 978-1-58839-727-0. Yale University Press | The Met Store