From Deana Lawson’s collaged drugstore photo assemblages to Somaya Critchlow’s dramatic painting, Present Generations— the Columbus Museum of Art’s latest acquisitions from the Scantland Family, building up the newly created Scantland Collection showcases a strong, compelling curation by the museum of its new acquisitions. Twenty-seven impressive artists currently making bold moves in the art world incorporate history, culture, and identity, and bring immediate awareness to concepts rooted in invisibility/belonging.

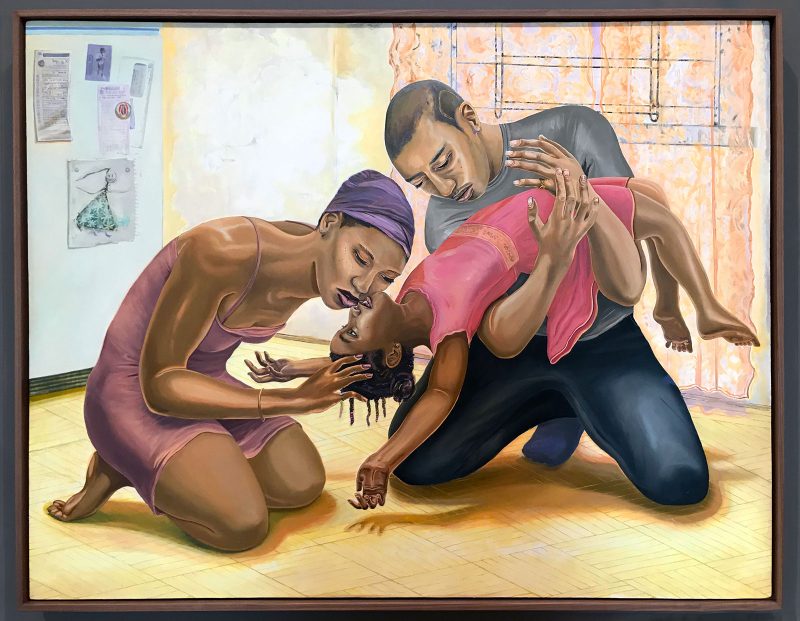

The three lithe Black figures in Aaron Gilbert’s “Love Still Good” seem composed in an arresting, tender dance on the kitchen floor. This medium-sized oil painting captures a rapturous moment within a family unit; their close, touching bodies expressing all-consuming emotion. The father holds up the daughter clad in a pink dress, arched upwardly against his chest. The mother is attentive to the daughter as well, her full lips and nose touching her daughter’s upside down face, her hand on the girl’s head of braids. The refrigerator suggests a deeper continued connection in the background— kid’s drawings and graded papers— a story of family pride and joy.

A moody cityscape coated in bits of magic glitter and shrouded in bits of golden yellow light takes generous attention in the next gallery. Jonathan Lyndon Chase’s large-scale multimedia painting, “Black Knight,” portrays two Black male figures inside their home, embracing, and an outsider riding a black horse, holding a pink plastic gun, a long snake around their shoulders. This acrylic, spray paint, marker, oil stick, and plastic work on muslin is an explorative abstraction explicitly conveying love, tenderness, and protection. The erotic pair have their windows invitingly opened, perhaps desiring to be seen, to have their passionate clinch be celebrated to a still dominantly heteronormative culture. Yet the watching horseman is not a voyeur looking in on the couple. They are outside, concentrated on the threats that would potentially harm the inside. The high-contrast pink colors, including the hot pink of the plastic gun included in the work, must be meant to disguise the danger, to emasculate the tools of oppressive violence.

Somaya Critchlow’s style is a Lynette Yiadom-Boakye-meets-Lisa Yuskavage collision. “The Weight of Silence,” a small oil on linen painting, centers a lone, alluring woman in the night. It is unclear whether her form squats or stands, thighs inches apart. The crescent shape is repeatedly depicted— the silvery half moon, the prominent arch above the woman’s head, the blond streaks in her coiffed brown hair, the amusement of her parted lips, her rounded breasts and thighs, and the orange and white curved rope in her hands. Her striped blue shirt is demure and almost up to her neck, but her upper arms push up her chest and her mini red-orange shorts could easily be mistaken for underwear. The moon is literally on her, watching her with a strange expression— maybe judgmental, maybe curious. Critchlow’s wide, generous brushstrokes cover a ghostly hint of Yuskavage’s gorgeous, sensually suggestive characters, delivering a beautiful, voluptuous figure pleased to exist, not a caricature stereotype of an existential Black woman.

Installation works by Derek Fordjour and Lauren Halsey indicate a clear interest in history. Fordjour’s “STOCKROOM Ezekiel,” a massive mixed media installation, reads similar to a storage facility. The piece is named after Ezekiel Archie, who saw slavery end at age six but was forced to work in the coal mines in his twenties due to convict leasing— slavery revised. Visitors are meant to enter inside Fordjour’s dusty encasement where sand coats the ground, the ceiling is a mirror, and sounds play simultaneously to the bright, flashing lights. Endless gridded shelves contain repetitive objects— busts, pyramids, trophies, hood ornaments, billiard balls. One side is unconstrained and the other has diagonal metal chains locking its inventory. This enclosed space can be explored through several contexts— the prison industrial complex, the limitations of complicated education systems that favors certain people over others, and living in a capitalistic society that generates manufactured profit while depreciating originality.

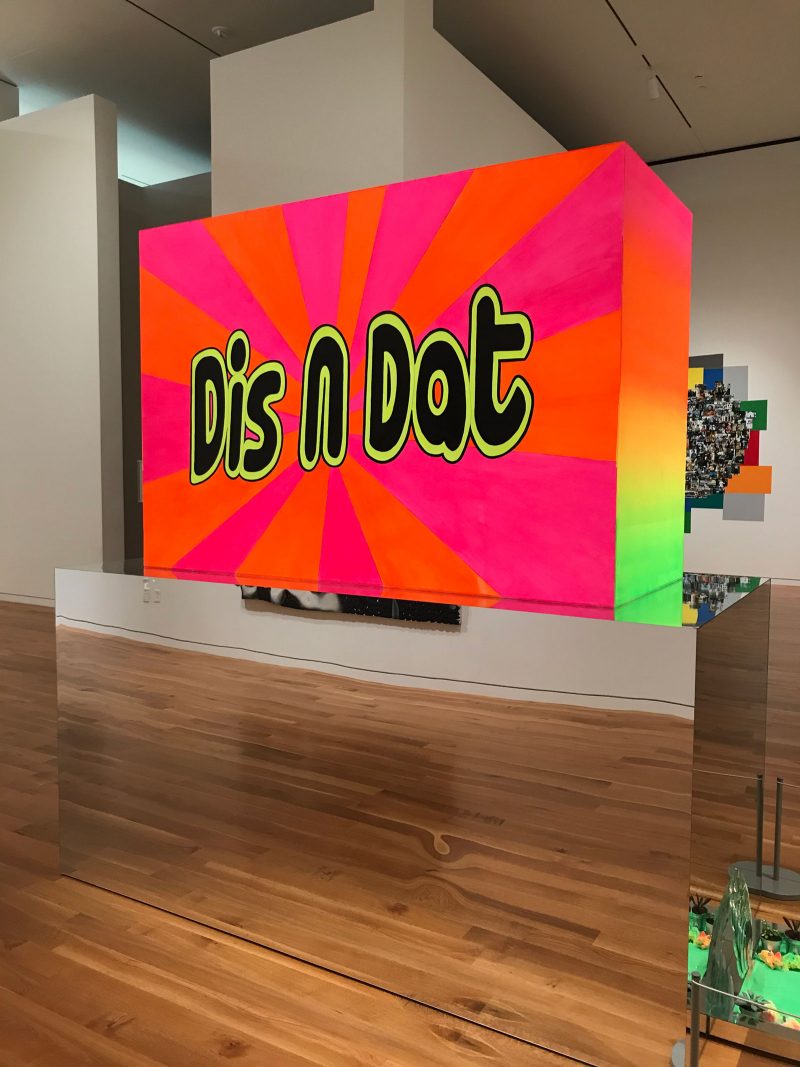

Meanwhile Halsey’s “The National Council of Negro Women Inc.” celebrates the nonprofit organization NCNW founded by activist, author, and educator Mary Bethune. This colossal multi-level and multiview structure has a neon- and fluorescent-hued “Dis n Dat” shop sign sitting atop a carefully crafted mirror block. At the floor level, strategically placed miniature potted plants, pyramids, and a cut out photograph of a Black woman— head and shoulders portrait, majestic diadem in her afro hair— sit on a bright green sandy ground.

This first selection of promised gifts to the Scantland Collection is a powerhouse and instills hope for other museums worldwide to bring a more inclusive edge to their contemporary sections. It also invites a more engaged public; many having longed to see themselves exist on the walls and mounted on pedestals— in paintings, drawings, photography, sculpture, and beyond.

“Present Generations,” the inaugural Scantland Collection exhibition, is up at the Columbus Museum of Art until May 22, 2022.