Emma Amos: Color Odyssey at the PMA through January 2, 2022 not only reveals the work of a powerful and little-known painter and printmaker, but also makes clear to viewers who wish to see her work today, the artistic and professional challenges facing an African American woman who would become an artist in New York City in the mid-1960s. The first room of the exhibition reveals Amos’s skill within the prevailing formal devices of abstraction and her resistance to it. “Shepherd’s Path” (1958), painted while Amos was studying in London, is a sensitive, abstract landscape consistent with the work of second-generation Abstract Expressionists such as James Brooks and Richard Poussette-Dart. “Baby” (1966) is a striking and colorful canvas which employs some of Pop Art’s strong, un-modulated colors and sets up a compelling tension among the forms – but it is not purely abstract. At lower left is a bust portrait of a terra-cotta-skinned woman in sunglasses and two pale-brown, bare legs appear at upper right.

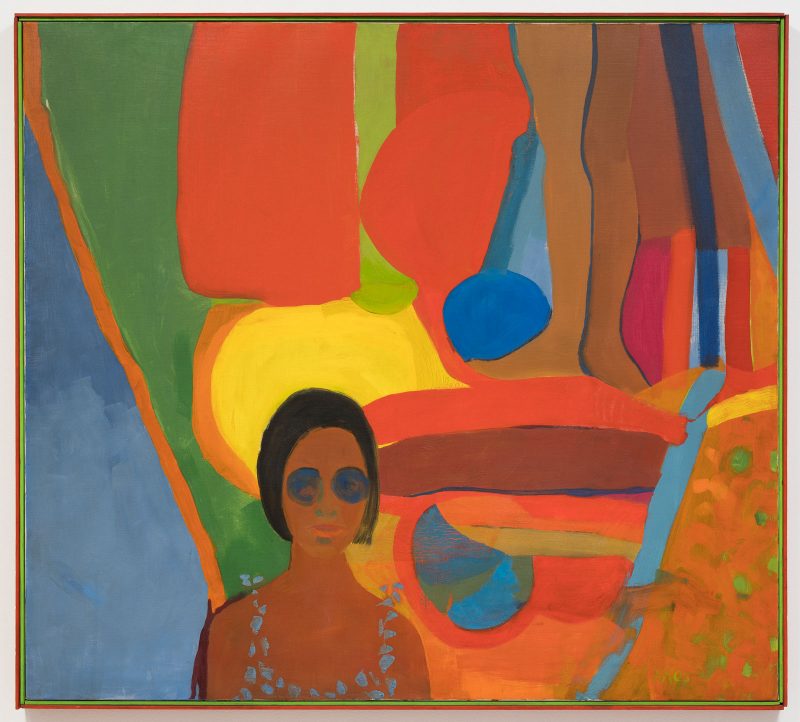

Amos’s name, if not her work, is most widely known because she was the sole, female member of the early group of African American artists, Spiral, which held its only group exhibition in 1965. For the “Black and White” exhibition she painted a 50 ¾-inch square, untitled work, abstract but for a recognizable hand at center. She sectioned off areas of the painting with vertical and horizontal lines so that it reads as a scene framed by a window, and in her work of the following year she continues the device of framing and complexity of indoors and outdoors spaces that Matisse had developed so effectively. The second gallery shows two further paintings which match the scale and palette of “Baby” and reveal the artist’s interest in portraying women of color as compelling subjects. “Seated Figure and Nude” (1966) shows a woman in a bathing-suit within a colorful but unidentifiable space; she is seen as if looking up at a viewer standing above her, while a darker woman exits the painting at right. Her pensive face might reflect that of the artist, asking whether this is a place where she belongs.

The gallery also displays Amos’s inventiveness as a printmaker and her extraordinary skill — nowhere more so than in the four-part, majestic “Creatures of the Night” (1985), one of the star works on view. The four collographs show Billie Holiday at upper left, sitting in a room with a window and at upper right, a gorilla in an indefinite space. At lower right is Josephine Baker and a stalking panther, both in profile within a dark, outdoors scene and at lower left a mandril, a primate of the tropical rainforest, shown partially in shade. Both women are dressed in dark clothing split to below the waist, revealing their breasts and belly-buttons. The settings are lush, smokey and atmospheric; everything is accomplished with virtuosic, painterly-looking technique. Amos created a serious and monumental, if enigmatic portrayal of the two performers by working against racist stereotypes of women of color as sexually-available and the association of African Americans with wild animals and the jungle — which Baker played with as part of her stage persona. “Creatures of the Night” is an homage to two powerful and inspirational artists who are comfortable in their own bodies.

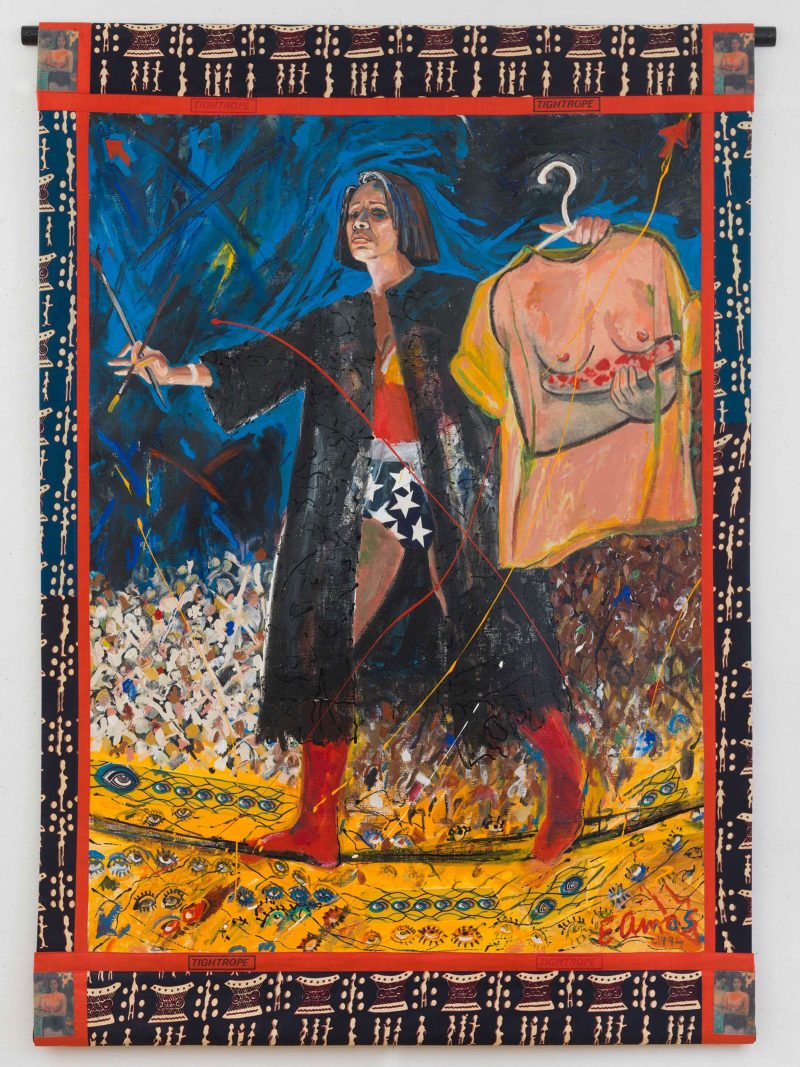

Emma Amos spent twenty-eight years teaching at Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, where she was a significant mentor to younger artists. She was involved with feminist groups and with other women of color in the arts; curated and was included in numerous exhibitions at non-profit spaces and schools; and had solo exhibitions internationally at galleries and in regional and small museums. She was awarded numerous artists’ residencies and fellowships, but had a minor record of sales throughout her career. She had no permanent gallery representation until four years before her death last year at age 83. It is against this background that we should understand some of Amos’s best-knows paintings, shown in the third gallery: a series of ironic works about the possibilities of a Black woman succeeding as an artist. Perhaps the best-known, “Tightrope” (1994), is a full-length self-portrait of the artist wearing the costume of Wonder Woman under a black robe as she balances on a tight-rope, brushes in her right hand while her left displays a tee-shirt, which depicts a detail of a Gauguin painting of a nude woman holding a platter of fruit before her breasts, both fruit and breasts offered for the pleasure of the male painter.

A second, ironic self-portrait, “Work Suit” (1994), shows Amos painting a nude, female model while wearing a jumpsuit decorated with the nude self-portrait of the British painter, Lucian Freud; a women painter needs to appear in the guise of the guys. Another investigation of the male artist is “Muse Picasso” (1997), painted on an apron made of African fabric, where the central portrait head of the Spanish painter is surrounded by various artistic models and written comments, as well as the face of Amos, looking up at the master. The paintings in this room exhibit Amos’s increased use of textiles; many are the wax-prints — decorative cottons popular throughout Africa — others are hand-woven African fabrics and hand-woven textiles made by Amos. She used the African textiles to create surrounds for her paintings in lieu of frames, and in the later work she incorporated her own hand-woven textiles as collage elements within paintings where they often formed the flesh of the female athletes she portrayed. One of the smaller paintings in this gallery is a surprise and a stunner: “Thank You Jesus for Paul Robeson (And for Nicholas Murray’s Photograph – 1926)” (1995). The full-length image of the nude Robeson, shown from behind, is taken from a series by the acknowledged photographer. Amos runs a sequence of Murray’s images down the left margin of the collaged painting, while a Graeco-Roman frieze of soldiers runs down the right side, all framed with a surround of African fabric. Her choice to depict Robeson as neither singer, athlete, or left-wing activist, but as a model specimen of a man and entirely equal to the Classical ideal, is unprecedented, as is her stance as a woman representing male nudity.

The final room includes several commanding series, which address race in a variety of ways. Some incorporate images of figures such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King; others portray life-size images of Black athletes; while a striking, dream-like series shows Black figures and circus performers falling through space, and another juxtaposes the Confederate flag with period photographs of rural African Americans in the South. This is the final venue of the exhibition, organized by the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia, Athens and is a compelling, if belated acknowledgement of a significant artist. If her work as a weaver and printmaker detracted from Emma Amos’s reputation in an art world that privileged painting and sculpture, her time may have arrived in a less hierarchical moment. Her gender and race were certainly an impediment that continues, as is clear in comparison with the attention the PMA is concurrently giving to Jasper Johns. But she should take a lead among the artists now receiving their due, and this exhibition is a worthy beginning in bringing her work to the widespread appreciation it deserves.

“Emma Amos: Color Odyssey” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Main Building: Morgan Galleries 150 & 151; Korman Family Galleries 152 & 153) through Jan. 17, 2022.