If I could start all over again, I’d be a professional demolition expert. I find the sensorial abundance of a building being torn apart deeply satisfying. The crunch of falling debris or of a wall cascading to the earth as a wave of structured mass disintegrates; the broken bits and shattered pieces; the hanging chunks, detritus and dust, is cathartic. Razing a building is the anarchist’s revenge on architecture.

Don’t get me wrong: I would not be pleased to be woken by the cacophony of a controlled demolition right outside my bedroom window every morning. But if it were my profession, at a remote site, far from home, with permission granted, and the proper gear–earphones, hardhat, protective eyewear–I’d be like a kid in a candy store, knocking buildings down with utter glee. And to be paid to do so! Monetary compensation would squash any residual feelings of guilt I might retain from adolescence when much smaller acts of destruction were considered socially unacceptable.

Johns Hopkins University (JHU) recently demolished its Mattin Center, a three-building, $17 million arts complex that opened on its Homewood Campus in 2001. As Edward Gunts outlines in The Architect’s Newspaper, the University removed the 20-year old structures to “make way for the new Hopkins Student Center, a $250 million, 150,000-square-foot ‘village’ for student programs and activities designed by the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and Shepley Bulfinch, with David Rockwell Group serving as interiors architect and Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates as the landscape architect.” This all sounds really impressive. But leaving aside the issue of not preserving an award-winning building complex only 20 years old, what does this suggest about the future of the arts at JHU? Destroying the art center in favor of a student center may sound great to students outside the arts, but how about to students in the arts (and their parents)? And what about the larger art community in Baltimore? Or even next door, at The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA)?

The demolition phase of the project took up the better part of the fall. There’s something almost poignant about a building being razed in autumn. It’s poetic, apropos the cultural and natural signifiers of death and decay momentarily merging in this ever-so fleeting moment, the falling leaves like so many bricks. And the dust! Ominous clouds of fine particulate matter blow out from the site, well beyond it, settling upon everything in their path like an almost imperceptible blanket of snow.

***

I work at the BMA. My full-time position is as a museum guard. But for the past two years, during the warmer months on one of my two weekend days off, I’ve assisted the objects conservator with cleaning the works in the BMA’s outdoor sculpture garden. It’s a welcome reprieve from standing around all day. It feels good to do actual manual work for a change. I enjoy working outdoors and seeing the fruits of my labor. While washing the sculptures, movements my body makes retrace those of the artists who created them. This, in turn, inspires me to ponder the relationship between art and labor and how even the word “artwork” contains a double entendre. In Maintenance Art Manifesto 1969!, feminist artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles outlines the common hierarchy of labor:

Development: pure individual creation;[…]

Maintenance: keep the dust off the pure individual

creation;[…]

Throughout her manifesto, Ukeles insists that maintenance goes far beyond domestic labor or “housework.” On July 22nd, 1973, Ukeles, with buckets of water, cleaning supplies, and a mop, washed the staircase to the entrance of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, as part of a larger series of performances meant to bring awareness to the work of custodial workers, so often overlooked in modern society. As former Curator of Contemporary Art at the BMA Helen Molesworth writes in “House Work and Art Work.” “Incisively, Ukeles does not refer to maintenance as domestic labor, or housework, for it is evident that such labor is not confined solely to the spaces of domesticity.”

Washing the “pure individual creations” in the garden further permits new artforms, enjoyed only by the workers who wash them. Sonic flourishes elicited when blasting them with a hose remind me that large bronzes are actually hollow, though seemingly solid. The bigger the work, the deeper the sound. Some pieces emit a pleasing musicality as they’re being sprayed. Seventh Decade Forest (1971-1976) by Louise Nevelson and Noh Musicians (1958/1974) by Isamu Noguchi register a surprising range of tones as water slaps against their metallic surfaces, like rain playing jazz music.

I see my role washing the art in the outdoor garden as an extension of my duties guarding it. Both jobs are forms of stewardship. As protectors of art, museum guards represent the first line of defense against the destruction or slow decay of cultural artifacts. Conservators practice a more specialized form of labor, requiring many years of education and training. Yet, without museum guards, conservators would have a much harder task, constantly having to clean and repair art that has been touched by absentminded visitors. Even without people touching them though, there would still remain a need for conservation, as dust–both inside and outside the museum–is perpetually accumulating on artwork. Dust, the eternal enemy of art!

***

As an avid observer of demolition sites, I’ve often noticed workers (and sometimes machines) spraying water onto debris as the extending arms of yellow excavators rip apart a building. I originally assumed this was done in order to prevent fires. More recently, however, I learned that this practice is meant to control the dust created by demolishing a building. There are so many materials that go into modern construction, it’s inevitable the massive amounts of dust will be raised in the process. Unfortunately, this form of “dust control” fails to stop the finest particulate matter from going airborne.

When washing the outdoor sculptures, we too use a hose to spray them down with water. There are often spiderwebs in the nooks and crannies of the sculptures and it’s fairly difficult to spray them away. The strands of web are quite sturdy and hold their own against the strong force of water blasted directly on them. We then handwash the sculptures with sponges and water mixed with Orvus, a biodegradable soap product. That usually takes care of the spider webs –for a time. Invariably, however, the spiderwebs reappear days later –and in the same spots too! The evolutionarily-honed instincts of the arthropod initiate the same process all over again, as though nothing happened at all.

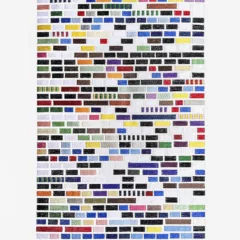

A few weeks ago, while wrapping up what we thought would be the last round of washing and waxing sculptures in the garden before winter, the objects conservator noticed small traces of fine particulate matter on the surfaces of a few of the sculptures. Looking up in the sky towards Hopkins, we discerned a large hazy cloud encroaching upon the garden like something out of a Stephen King story. Dust from the demolition site next door was quietly settling on the sculptures, our most recent efforts undone by the smallest of things.

We had to work a little later in the season due to the dust, but the outdoor sculpture-washing is done for now. Reflecting on my work in the garden this past autumn, I realize that I’m something like the spider, my previous efforts soon to be undone by forces against my will. I understand how I am but one agent in an interconnected web of creation and destruction. Artists will continue to make new artwork, which if deemed worthy by curators, will be protected for years to come by generations of conservators and security guards. Meanwhile, the spider will meticulously build her web again and again, strand by strand, only for museum workers to wash her work away like before, just as universities will have professional demolition experts raze not-so-old campus buildings–stirring up heaps of dust in the process–to make way for newer structures, which will in turn need to be cleaned and maintained, only to one day be destroyed themselves. And I’ll return again next spring to begin my Sisyphean task once more.