When Delaware Art Museum Curator of Contemporary Art Margaret Winslow was researching the 2015 exhibition Dream Streets: Art in Wilmington 1970–1990, she came across a checklist for an exhibition of work by African American artists that took place in 1971 at the Wilmington (DE) National Guard Armory (now St. Anthony’s Community Center). Not a native Delawarean, and not even born at the time of the 1971 show, Winslow was not aware of it. Afro-American Images 1971 was well attended, and many regional politicians and leading citizens were at the opening reception. It was supported in part by a grant from the then new (1969) Delaware State Arts Council.

The curator of that original exhibition, Percy Ricks, (1938-2008) dedicated it to the memory of his Howard University professor and mentor, James A. Porter (1905-1970), a renowned artist and art historian. Ricks was an artist and teacher and a founder of Aesthetic Dynamics, Inc., a nonprofit organization dedicated to strengthening the presence of the arts in Wilmington. After attendance at Howard University, Ricks earned advanced degrees from Columbia and Temple Universities. In 1948, he became the first full-time Black art teacher to be hired in the Wilmington public schools. By the time of the Afro-American Images exhibition, he was a well-established artist and teacher with many connections to Black artists across the country, but especially those on the East Coast, in part through his Howard University ties.

Over 130 works of art were included in the original exhibition. Curator Winslow recognized many of the names on the checklist, including Romare Bearden, Sam Gilliam, Barkley Hendricks, Jacob Lawrence, Norman Lewis, James A. Porter, Faith Ringgold, Alma Thomas, Charles White, and Hale Woodruff. The exhibition consisted of work by emerging artists as well as the luminaries mentioned above. One of Ricks’s goals was to demonstrate the extent of the talent of Afro-American artists, countering the misconception that there were no or very few Black artists making contemporary art.

Historically, 1971 denotes an important moment for Wilmington. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, and after rioting and looting took place, the National Guard was called and occupied the city for nine months. The negative outcome from this occupation reverberated for years. The show was first offered to the Delaware Art Center, soon to be renamed the Delaware Art Museum, but the leadership did not respond. The museum did not have a history of reaching out to the Black community, or as historian and artist Simone Austin states, “To write about the Black presence at the Delaware Art Museum is to recall the absence of curators, exhibitions, and artists.”* This situation, until somewhat recently, is, sadly, typical of many museums across the United States.

Winslow, approached Dr. Newton, who she had consulted for the “Dream Streets exhibition,” to discuss the possibility of restaging the Percy Ricks exhibition at the Delaware Art Museum to recognize and document it upon its 50th anniversary.** An advisory committee of knowledgeable individuals, including scholars and community leaders was formed, and the result is the current exhibition with an attendant catalog. The 2021 Percy Ricks exhibition is part of a concerted effort by the DAM, located in the city, to reach out and connect with Wilmington’s Black community.***

The scope and scale of the restaging project was enormous. How do you track down all the art that was on view in the 1971 presentation? Winslow recalls that they could immediately identify and locate examples by 66 of the artists.**** Also, a number of collections of African American Art went up for sale over the last 3-4 years, which helped with sourcing the art. They were not able to find all the objects on the original checklist, but the current show includes comparable pieces in style and date so that most of the artists in the 1971 exhibition are represented, with 100 works on view. Lenders to the DAM restaging vary from private collectors to museums. The result is a stunning exhibition that presents a view of modernism over many different styles, subjects, and techniques from an important period in the development of contemporary art.

A diversity of approaches was employed by the artists, from those who concentrated on African sources to those who explored political and sociological issues, to those who were accomplished in formal abstraction. The ideas that inspired the artists can be traced in part to two Howard University Professors, the philosopher and supporter of the arts, Alain Locke, and Ricks’s mentor, James A. Porter. The two esteemed professors did not always agree on the subjects and styles for Black artists, but their ideas reverberated even into the 1970s.***** In 1925, Locke published The New Negro to which he contributed five essays, among them, “The New Negro” and “The Legacy of Ancestral Arts.” He encouraged looking to African art and Black culture for inspiration. Porter published his influential book, Modern Negro Art, in 1943, in which he established African American artists in the context of American art. Ricks believed in a Black esthetic with roots “embedded in the rich soil of the cradle of civilization.”******

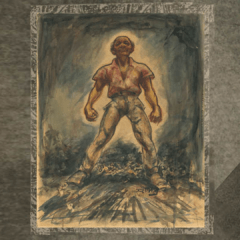

Hubert Howard’s “Black Orpheus” demonstrates a classical subject, the Greek god of music and poetry, represented here with several powerful dark-skinned figures. Highly saturated expressive color and abstract forms demonstrate Howard’s knowledge of modernism; Matisse’s impact on Philadelphia artists, where Howard lived, was likely through the Barnes Foundation. Many Philadelphia artists learned from its collection which includes works by Seurat, Cézanne, Matisse, Modigliani, and other important modernists. African sculptures are on view there as well.

New York City artist, Hale Woodruff, is best known for his abstract expressionist paintings that often refer to African arts and culture. In “Celestial Gate,” he suggests the carved wooden doors of the Dogon people of West Africa. His dramatic image, “Ancestral Memory,” while abstract, includes a mask-like image of a face. One of Sam Gilliam’s draped abstract canvases was included, here represented by a 1971 untitled work by the artist. Another painter working abstractly was Alma Thomas, who had roots in Wilmington, having taught there before attending Howard University. The DAM shows the same painting of hers that was included in the 1971 exhibition, now owned by the Smithsonian Museum of African American Museum of History and Culture.

In addition to Thomas, Ricks presented work by other women well known today, among them: Lois Mailou Jones, Faith Ringgold, and Samella Lewis. Most people recognize Ringgold’s textile paintings, but she painted in oil on canvas before she moved to her renowned quilts. Jones taught at Howard from 1930-77, and Lewis is a scholar and curator in addition to being a practicing artist, publishing an important art history textbook, Art: African American in 1978.

“Waiting,” a lithograph by Ernest Crichlow is a representational image of a young Black girl behind a barbed-wire fence. Crichlow often depicted images about racism. He was associated with the Harlem Renaissance, and in 1969, just two years before the Wilmington exhibition, he co-founded a gallery in New York, NY with Norman Lewis and Romare Bearden, whose works also were included in the 1971 exhibition. Lewis’s abstract expressionist images sometimes contain figures or other signifiers referencing Black life. Bearden, who is best known for his collages, became an advisor to Ricks on the exhibition.

While not able to recreate the original exhibition exactly, Afro-American Images 1971: The Vision of Percy Ricks is close enough to honor the vision and dedication of Percy Ricks. The show is very important. It’s a museum mea culpa and is not only timely because it is the 50th anniversary of the original show, but also represents an attempt to reverse the role museums played in ignoring Black artists. And it is just a darn good show. It is well worth a trip to Wilmington.

“Afro-American Images 1971: The Vision of Percy Ricks,” on view at the Delaware Art Museum thu Jan. 23, 2022. Collaboration between Aesthetics Dynamics, Inc. and the Delaware Art Museum. Catalog available here.

Footnotes

*Simone Austin, “The African American Presence at the Delaware Art Museum,” in Afro-American Images 1971: Percy Ricks, exhibition catalog, The Delaware Art Museum, 2021, 29.

**Zoom interview by author with Margaret Winslow, December 16, 2021.

***The total population of Wilmington, Delaware in 2021 is just under 70,000 with Black or African American being 58.26% of the composition of the city.

****Zoom interview by author with Margaret Winslow, December 16, 2021.

*****Rizvana Bradley, Margo Natalie Crawford, John McCluskey, and Charles Henry Rowell, “James A. Porter and Alain Locke on Race, Culture, and the Making of Art: A Roundtable” Callaloo. 39, no. 5 (2018): 1171.

******Percy Ricks, “The Black Esthetic,” 1976, essay from the Percy Ricks files quoted in Dr. James Newton, “Percy Eugene Ricks: Memories, Musings, Mentorship,” in Afro-American Images 1971: Percy Ricks, 56.