[ED. NOTE: This post contains imagery that is NSFW.]

Joan Semmel: Skin in the Game at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) through April 3, 2022, is the first solo museum exhibition for an artist whose work is widely known in reproduction but rarely seen. It’s about time. While Semmel has long been acknowledged within the history of feminist art, her work offers an example of engaged figuration that will interest many young artists. She also offers an exploration of the body as seen and felt, and depictions of women and their changing relationship to their aging bodies that will be compelling to anyone who thinks about the human condition.

When Joan Semmel returned to New York City in 1970 after a decade of living in Spain, she was an established, abstract painter. Her choice to turn to figurative painting and the subjects she explored reflected her current concerns, and became exemplary expressions of second wave feminism. Her work was also scandalous. Semmel depicted couples in the midst of sexual intercourse, which ladies weren’t supposed to do. She not only insisted that women were entitled to desire and engage in sexual activity, but that a woman’s point of view had been entirely lacking in previous works by and for a male audience.

The female sexual impulse Semmel portrayed responded to more than the visual. While the visual response might initiate foreplay, consummation is often in the dark, dominated by the senses of touch, smell, taste and sound – and by imagination. Her painting, “Green Heart” (1971), a challenge to read because of its generalized forms and odd perspective, is the only work of art I know that even approaches my own sexual experience. In the center of the painting are the green back and buttocks of a man; a small bit of one leg is shown, clasped within the pink legs of his partner. We see her left hand on his shoulder and the only visible part of her face is her open mouth. That and her shocking pink left foot and the orange line that runs along the inside of her leg are perfect representations of orgasmic release.

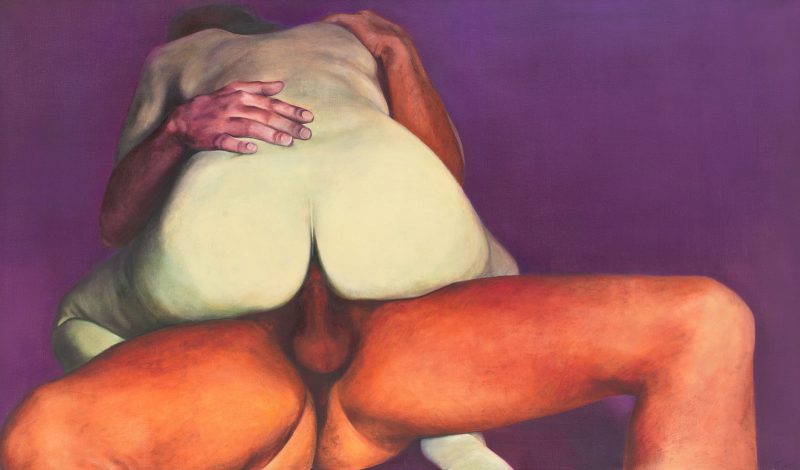

Slightly later she turned to pornography for considerably more detailed images of penetration and hired models whom she photographed for studies. The resulting depictions are often seen from unexpected angles, closely cropped, with colors as imaginary as the green of the aforementioned lover. They almost always include a caressing hand. “Purple Passion” (1973) takes a conventional, pornographic subject, a closeup of a woman’s buttocks atop the man who penetrates her, and infuses it with the tenderness of his hands on her lower back and shoulder, and a purple atmosphere into which the figures seem about to melt.

Her most didactic work is the funniest: the triptych “Mythologies and Me”(1976), in which she makes explicit the difference between a sensitive examination of a woman’s body and images more commonly created by men that range from pornographic to caricatural and hostile. In the center is a view of the artist’s breasts, right forearm and legs as seen when she is recumbent and observing herself. The angle is so extreme that it takes a moment to figure out what is actually shown. To the left is a conventionalized and faceless “Playboy” model with one revealed, frontal breast and a strategic arrangement of frilly garter belt and feather boa that calls attention to what it obscures. She is mirrored on the right by the equally target-like left breast of a woman as painted by de Kooning, anxious-looking and harpie-like, with a claw for a foot.

In three portraits from 1982 Semmel uses mirrored images to connect the subjects with each other and interweave art, vision and memory. A portrait shows the artist’s father sitting in front of a mirror that, reflecting another, unseen mirror, produces receding images of the back of his head; her mother appears through an open door at the right. The ever smaller images of the back of his head are a touching metaphor of the parent receding in death but remaining as memory, captured by photography and painting. Semmel’s frontal self-portrait shows her, as she could only have seen herself – in a mirror. In her right hand are several brushes as well as the photograph of her father that clearly served as the basis for his painted portrait. Over her shoulder is a painting of the mid-section of a nude man and his reflected back. The artist has taken off her glasses, which she holds in her left hand; she has the look of someone lost in thought – perhaps thinking about her relationship to the two men. The third painting is the one depicted in Semel’s self portrait: a study of her partner, David, looking as though he is mid-conversation – his right hand is out of view but likely putting down a cigarette as he exhales smoke. The back of his body, like that of Semmel’s father, is reflected in a mirror.

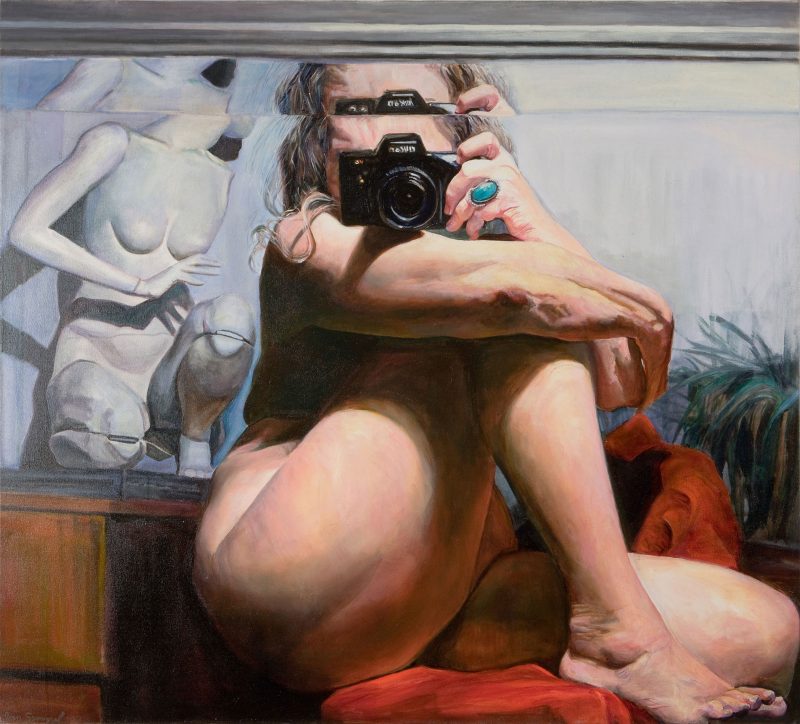

In the late 1980s Semmel produced a series of paintings of nude women engaged in everyday activities in gyms and locker rooms as they bathe, dress, stand on a scale or apply makeup. They are the sort of un-romanticized images of actual, middle aged women that we rarely see, and reveal the contrast between their attempts to forestall the effects of time with exercise and cosmetics and time’s inevitable imprints on their flesh. Semel caught her own reflection in some of the paintings, which creates a multiplicity of perspectives and uncertainty of spatial relations, that she had previously explored in drawings that included their own source photographs, and would pursue further in paintings where she layers multiple images of bodies.

Her glimpses of her mirrored self in the locker rooms would evolve into an exploration of her own, aging body that has continued to the present.There is, unsurprisingly, a tradition of artists’ contemplations of death as they age, but exploration of the artist’s aging body is less common. Picasso was clearly looking death in the eye in his last self-portraits, but Rembrandt explored his aging visage in a series of self-portraits, as did Edvard Munch. Jo Spence and Hannah Wilke revealed the ravages of the final stages of disease on their nude bodies at death’s door, but Semmel’s paintings are about living with age, not about dying. Alice Neel portrayed her aged self nude, in the act of painting and with the same merciless attention she gave to her other nude subjects, so it is hard to determine her concerns. The only equivalent, recent example I can think of is photographer John Coplans, who seemed to find a liberation to play in images of his gnarled hands, flabby biceps and hairy paunch, and he manipulated his body’s forms like clay.

Semmel’s nude self-portraits show a woman coming to terms with her own aging flesh and thinking about how she might appear to others. Some works emphasize details and the use of mirrors, while others return to cropped close-ups and emotive, if unrealistic colors. I’m only slightly younger than Semmel and I find her still beautiful and can’t imagine that her male contemporaries wouldn’t also; I hope I age as well. But the public image of older women accords no place for their physical pleasure or sexual desires, so, much as she did with her paintings in the 1970s, Semmel here breaks taboos about the depiction of women, their bodies and their thoughts. If we find the subject of these paintings unpleasant and turn our eyes away in favor of the fantasy of eternal youth that commercial interests offer, we are only setting ourselves up for a painful future rather than an acceptance of old age as one more stage of life.

“Joan Semmel: Skin in the Game” – on view thru April 3, 2022, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), Fisher Brooks Gallery.