At the entry to Jennifer Packer’s retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, hangs a wall-sized painting of a yellow green interior— “Blessed are Those Who Mourn (Breonna! Breonna!).” The lower part of the image is occupied by a Black man in repose, his head and torso built up through semi-transparent umbers and warm red browns. The citrine of the tufted sofa he lays on pushes through his skin, as if his body and the furniture form their own entity. His aqua basketball shorts flash blue, contrasting the flat plane of pink above him. The painting was composed from images of the interior of Breonna Taylor’s apartment that were released to the media after she was shot and killed by Louisville Police on March 13, 2020. Packer has rendered a chorus of household items around the figure—an iron, a chessboard, a standing fan, a houseplant. Her economic brushstrokes describe convincing forms without relinquishing their enmeshment with the atmosphere. Here, the particular matters to the sense of the whole.

The tension between found identities and looser abstract passages of paint accompanies Packer’s visual language across the show’s 31 paintings and 4 drawings. On tour from Serpentine Gallery, London, the exhibition spans a decade of work. The earliest paintings have more concrete shape and color relationships that Packer later expands into monochromatic compositions. In “Carolina” (2011), a floating black door frames a resting person laying casually in a pink and blue garment, another figure’s shirtless torso reveals neon orange underpainting through the brown transparency of their skin. The people and their environment appear quilted together, patch of color next to patch.

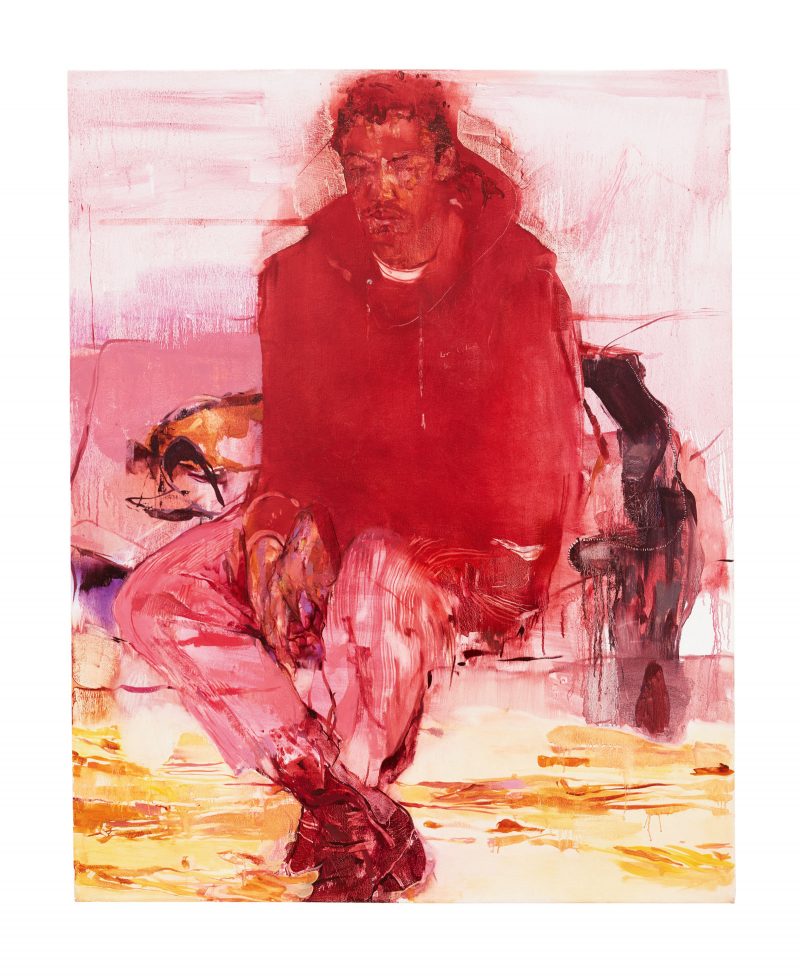

By 2015, Packer transitioned to working with vibrant monochrome palettes. In “The Body Has Memory” (2018), a young man in a red hoodie sits with his hands resting in his lap. His face, hands, and feet are all painted in the same shades of red-violet, sometimes scraped away to reveal transparent pink, or layered with subtle dabs of purple and brown to shape his flesh. The shroud of color protects the subject’s inner world while leaving open an invitation to empathic viewership through the moments of detail.

The show’s title, The Eye is Not Satisfied with Seeing, comes from Ecclesiastes 1:8, the biblical passage characterized by the melancholy that attends the limits of human knowledge on earth. In the context of Packer’s paintings, the line suggests that the eye is hungry to understand. The eye not only sees, but tarries with desire and the realm of the unseen. The lack of dimensional representation of Black people, especially Black women, in the history of painting also leaves the eye unsatisfied, searching. Packer’s vision reveals the historic absences by representing alternative systems of valuation and dignity.

In her interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Packer describes the connection between vision and light: “I think I approach painting through questions of hierarchy, beginning with what’s of the deepest significance. Historically, light is value, so something that’s given value is blessed with radiance.” Packer manipulates the value inherent in image-making to surprising ends. History abounds with examples of value being relegated to people in power or reinforcing the existent social order. But through Packer’s brush, painting becomes a tool to trouble with conventional hierarchies in favor of more complicated representations. Her portraiture not only includes people who are not reflected in the annals of history, it extends attention to their environment, to flowers, box fans, and socked feet.

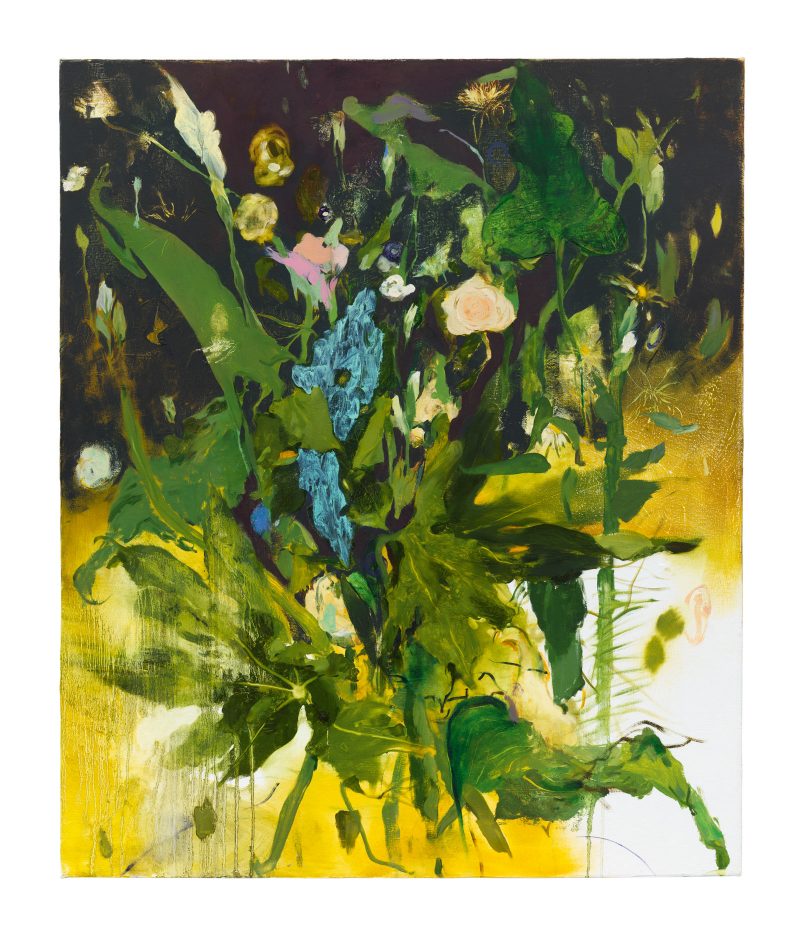

The show includes several paintings of funerary bouquets that signify Packer’s grieving process for very public and brutal deaths of Black people whom she names in the titles, including Sandra Bland and Laquan McDonald. The flowers hold space for absence, but they are also tender offerings of beauty in celebration of the lives they represent.

In the same interview, Packer cites Caravaggio’s dark images of suffering and his urge to paint raw vulnerability as longstanding influences on her work. Packer’s paintings echo Caravaggio’s sensibility to reveal significance without obliterating mystery. In the drawing, “The Mind is Its Own Place” (2020) two figures are locked together in perpetual bond, their body parts fading in and out, while the white of the paper marks the bright segmentation of a knee coming forward. Packer has built a sense of depth through careful distribution of light and darkness—the recognition of a face, of fingers, and toes, emerging through the deeper mid-tones framed by scumbled darkness.

Packer’s resistance to overdetermination reminds me of Édouard Glissant’s essay, “For Opacity,” in which he argues against the mechanisms of colonial racism and barbarism through advocating for each person’s right to remain opaque. The sacred interiority of personhood, so undermined by racialized violence, is also violated by modes of representation which insist upon a singular or stereotypical identity. In order to preserve those vital differences which formulate thought, he argues, “We clamor for the right to opacity for everyone.” Packer does not shirk from the power of revealing her relationship, at times her love, for the people she paints, but in every stroke is also a preservation of their humanity, their opacity.

“Jennifer Packer: The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing” on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC, through Apr 17, 2022

Author’s Bio

Kate Brock is an art writer and painter based in Philadelphia, PA. She graduated from the MFA in Art Writing program at the School for Visual Arts, NYC, where she received the Paula Rhodes Award for excellent contribution to the discipline of Art Writing. She writes about Anarchism, micro-histories, vegetal life, and the pleasure of painting. Follow her work at www.katherynbrock.com.