Behind every white male is a woman artist deserving the same praise, especially the rarely celebrated Black woman artist.

Jasper Johns’s exhibitions may be taking over two cities— Philadelphia and New York respectively— but two prolific Black women artists are also on the tickets – Emma Amos and Jennifer Packer. This essay will cover the work of Emma Amos. Born seven years after Johns and dying almost two years ago, Emma Amos, a gifted painter and printmaker, takes the three lower level galleries at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Meanwhile, the living and prominent Johns has the main special exhibition spaces.

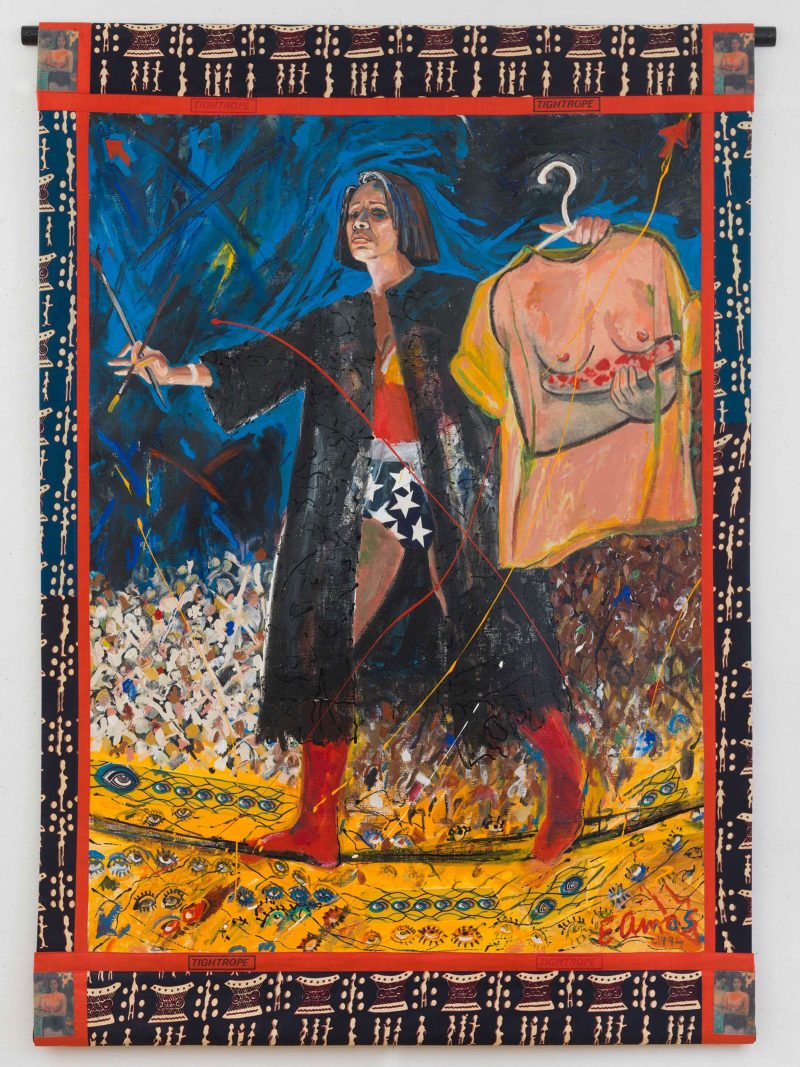

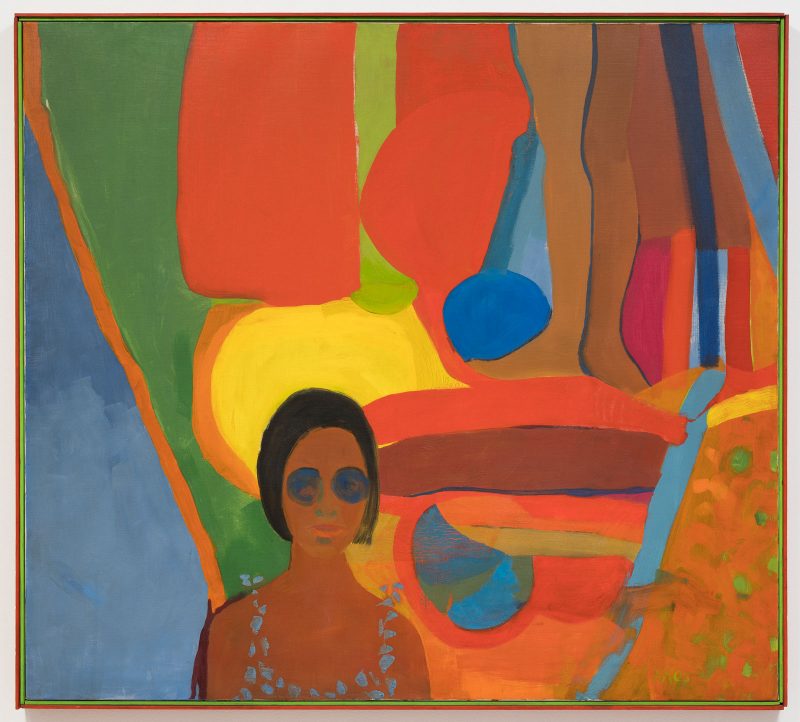

Despite the location, Color Odyssey triumphs as a celebration of the revolutionary brilliance that Amos left behind. These three galleries bring feelings of unjust agony and desire to visibility. Emma Amos belonged to painting and drawing and deserved flowers a long time ago— way before now. Her profound legacy is steeped in authoring her autobiography across several disciplines, broadcasting the undeniable importance of women’s history, and openly criticizing art canon darlings such as Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol. She ferociously bit the hands that refused to feed her— daring in fiery self-portraits wearing white male bodies or situating herself in the European beauty standard. She crafted a balance between abstraction and representation— rendering figures in a classical precision and placing them in flat planes of intense color. Amos centered womanism and blackness in sharp, imaginative paintings that were a grand mixture of pop art culture, color field painting techniques from Mark Rothko or Helen Frankenthaler, and her own innovative edge.

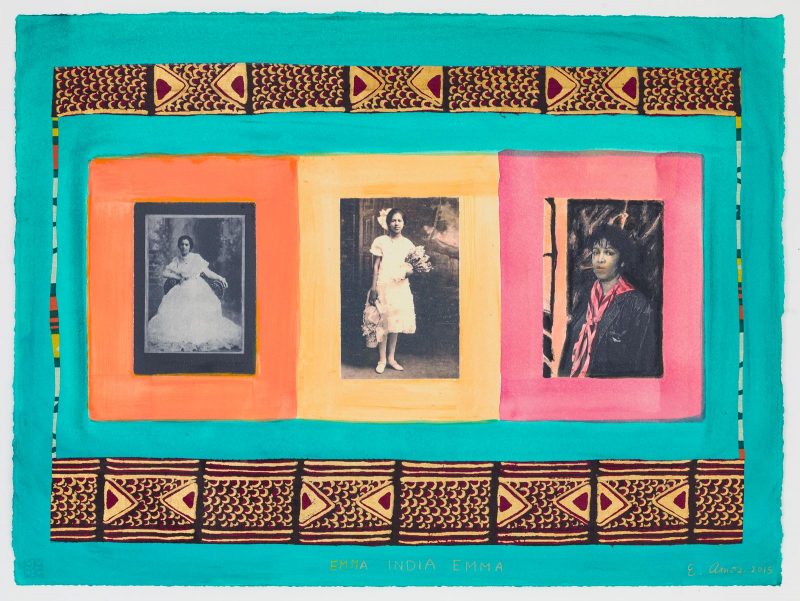

In addition to painting, Amos’s family photographs are integrated in several prints. Often a sign of privilege and the best instrument of preserving family lineage practice, photographs are key to understanding wealth and status. For example, in the silkscreen “Emma India Emma,” vintage photographs of Amos’s grandmother, her mother India, and Amos herself are blocked in orange, yellow, and red and incorporate a turquoise background. A patterned border frames the photographs and interrupts the turquoise. The three photographs also tell a story of breaking tradition. Amos’s fair skinned grandmother and mother are dressed in lacy white dresses and smoothed hair to show a similar delicate facial structure, appearing every inch like demure debutantes. The grandmother’s chair is ornate and the mother carries two baskets of gorgeous flowers. Yet Amos wears a heavy denim jacket, her striped scarf is dyed the red of her color block, and sparse bangs hang over her very direct eyes and fierce expression. Although it seemingly implies that her red adds to the yellow of her mother to make the orange of her grandmother, Amos was not following their path. She embodies moving away from expectation by becoming more than pure decoration. It is an agonizing choice between societal expectations of women (marriage and children) versus feminine independence (becoming an artist in a white male dominated profession). “Emma India Emma” weighs the benefits of both.

In “To Sit (With Pochoir),” a medium sized etching and aquatint with stenciled coloring print, two women in one-piece bathing suits recline on what looks like a patterned blanket their bodies intimately close together in companionable comfort. On the left side, a woman in black, stares out, as if at the viewer. One hand is under her chin and the other drapes across her stomach. On the right, the second woman has her back facing her companion. She wears red and her eyes are closed in serenity. Her one revealed hand lays at the top of her thigh. Throughout every carefully rendered line and shape of her characters, Amos suggests a kindred bond between them. She leaves room for many interpretations. The curvy figures, detailed patterns, and asymmetrical composition are also reminiscent of Mikalene Thomas setups.

Color Odyssey hits all the right notes and pushes the buttons necessary to warrant reaction. Some will walk through and see their own families depicted in Amos’s bright, vivid paintings or find their African fabrics stitched in her screenprints. Some will get her work right away. They have been in her shoes. They have expressed her anger, her rage, her passion, and her love. Beneath the surface of the heart, however, rests the question— why does it always take forever to display on these guarded walls? Why must we no longer breathe in order to earn this reward? Emma Amos, receiving this high acclaim after her death, is heartbreakingly bittersweet. This familiar road known to many including the uncharted painter Vivian Browne— a friend to Amos mentioned in an artwork— reinforces the sentiment that so few women and Black artists receive true success in life. Disadvantaged artists can fall under the radar well before prominent galleries and museums take notice. Yet Jasper Johns and his ilk remain having opportunities to see their achievements and rejoice in them. Thus, the most ironic insight to take away from Color Odyssey is that Amos constantly critiqued the problematic industry and foreshadowed her place in it. The Philadelphia Museum of Art just let her ghost know where her place was.

“Emma Amos: Color Odyssey,” through Jan. 17, 2022, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Be sure to check the website for many images and a video.

Read Andrea Kirsh’s piece on the Emma Amos exhibit: “Powerful and overlooked, “Emma Amos: Color Odyssey” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art reveals an innovative and feisty woman artist“