Laurence Salzmann‘s recent show, Creatures Real and Imagined, reveals how deeply our lives are intertwined with the non-human animals with whom we live on variously intimate terms–as herd animals, co-workers, pets, friends, and creatures we can dream into being and mourn when they pass from our lives. Salzmann’s work touches on the wide range of human/animal relations, but to appreciate its originality, we need to see it as part of a dialogue between the type and the individual, a dialogue that has only recently been refined, as we have sharpened our gaze and our understanding–post Peter Singer–of animals.

The very long tradition of animal representation goes back to the earliest torchlight drawings on the walls of the darkest caves, drawings that allow us to see different types of creatures, but not individuals. Even when humans transformed animals into symbols of individual moral virtues (Aesop’s fables, the medieval bestiary) the creatures themselves were types. Not until the paintings of the early 15th century do cats and dogs abandon their allegorical status and begin to show up as credibly individual household familiars. At last, by the mid-19th century, Edwin Landseer and others were painting dogs and horses as subjects in their own right, creatures with names and histories worth remembering.

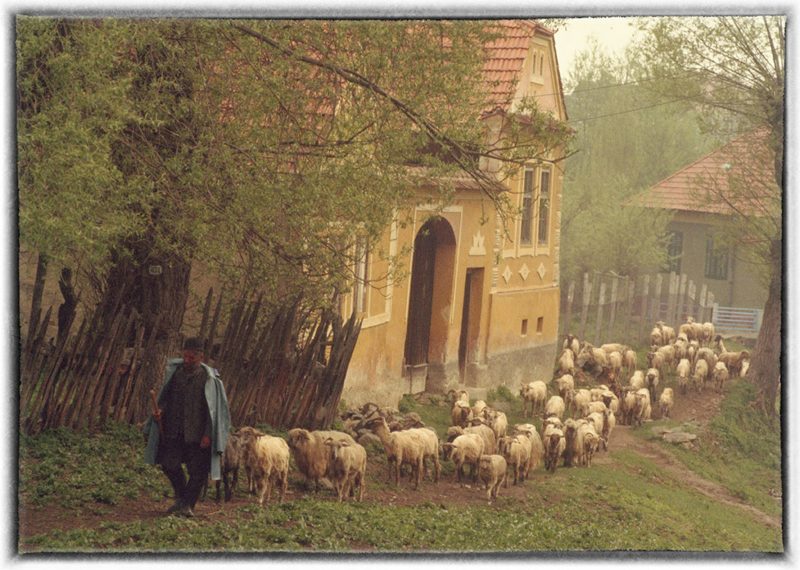

Photography, by its very nature, would seem to individualize the creature; but context is everything. Seen as a herd, there’s little difference between one sheep and another, and in his photographs of the pastoral life, Salzmann portrays the herd qua herd, a collective, an unwieldy unit that needs to be managed by shepherd and dog. The pastoral life may be the oldest of stories, but it has generally been portrayed in static terms, despite the fact that shepherds are always on the move as they drive their herds from one region to another. In Salzmann’s photographs, we see real sheep and real shepherds, in motion as they move across landscapes and over roads; and we see the working relationship between shepherd, dog, and sheep portrayed with equal respect for man and beast. Salzmann spent a year living with the transhumant shepherds of Romania, depicting the symbiotic bond of their survival and their movement together from the mountain highlands in the summer, and back down to the valleys in winter. With his anthropological background, Salzmann characteristically sees the animal as an integral part of human society, not only in pastoral Romania but in other folk cultures he has photographed throughout his career, from Eastern Europe and Turkey to South America.

The sheepdog is of course an integral part of the shepherd’s existence, and we can easily imagine the dog’s full-time employment in the pastoral life as a happy one– racing around, boss of the herd, esteemed by their masters, well fed. Sheepdogs are not horses in harness, nor are they idle cats. In general, dogs do all kinds of useful things, from guarding property to finding survivors in wreckage, from serving the blind to sniffing illegal drugs. But the life of the sheepdog–maybe I’m romanticizing it–seems pretty near ideal.

A sheepdog who is not employed is another story altogether, and Salzmann features two such dog stories in his show, each the narrative of an individual dog. Salzmann is not the first to individualize his canine subject–think of Jack London’s great dog tales–but where London creates an interior subjectivity in his fictitious animals, pushing them into heroic careers as surrogates for our own dear selves, Salzmann allows the dog to be their own dog selves, imbuing his images with respect for their otherness at the same time that he focuses on the bond between dog and human. In one of his picture stories, Garip (1995-2008) Returns to the Life He Left Behind, Salzmann eulogizes a sheepdog brought to America by the photographer’s wife, Ayse, from an archeological site in Gordion, Turkey. Garip’s new life as a Philadelphian in the Salzmann family was a happy one, from the photographer’s perspective, but Salzmann’s keen awareness of Garip’s deracination is the creative source of the photographic series that imagines him, as in a dream, returning to his country of origin and to his lost life as guardian of sheep. In dramatically overlapping, palimpsestic images, Salzmann, working with collaborator James Rowland, transforms his photographs into a mournful, phantasmagoric montage, a moving memorial to the photographer’s respect for the dog’s otherness.

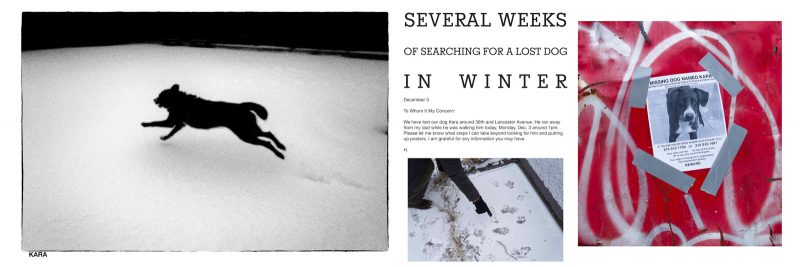

The other dog story, Several Weeks of Searching for a Lost Dog in Winter, is based on a narrative written by the photographer’s daughter, Han Salzmann, with photographs by Salzmann. The generic title–searching for a “lost dog”–ironically belies the intensity of the tale and the individuality of the sheepdog, Kara, who escapes from Salzmann while they are on a walk. The narrative is a collage of messages and reports detailing the anguish and anxiety of the months-long search, marked by numerous false leads, while the photographs record the persistence of Salzmann and his wife (typically at 6 AM on cold winter mornings) in combing nearby West Philadelphia neighborhoods, vacant lots, rail yards, anywhere the dog might have been briefly spotted. The Salzmanns are looking for a lost child, but in this case, the child is capable of surviving for two years on her own, until she is by chance befriended by a stranger whose kindness eventually restores her to the Salzmanns.

Garip and Kara are individual dogs, but the point is that Salzmann resists the almost irresistible urge to anthropomorphize them. He allows them to retain their otherness. It’s worth making this point, given that many Americans inhabit a Funniest Home Videos culture, in which dressing up a dog or cat on Halloween is considered high entertainment. Such anthropomorphic humor dates back at least to the late 19th century comic pictures of dogs sitting around a table in derby hats, playing poker and smoking cigars, a disservice to both humans and dogs. Even James Balog, in his impressive series of ape portraits, poses his subjects–alone or in conjunction with female models–so that they appear uncannily “human,” thus erasing the line between monkey and man as if to beg the question: how different are “we” from “them”? The logic here is that if we can see ourselves in them, why don’t we treat them with respect? Yet behind that argument is the assumption that we can only respect and protect what is like us, not what is unlike us. Salzmann’s tributes to Garip and Kara allow the dogs their otherness while also insisting on our human respect for them.

While the photographer’s tributes to these two individuals–Garip and Kara– demonstrate the power of art to consecrate the animal-human connection, the “imagined” animals in the show’s title speak to a different dimension of the imagination, the power to create fancies that stretch our minds beyond reality. Salzmann’s friend, the celebrated artist Holley Coulter Chirot (1942-84), is the show’s inspiration for this mode, and she is here represented by six dark and playful etchings that evoke the medieval bestiary in the dream-like spirit of Bosch and Dali. Salzmann adds his own tribute to Chirot in five photo-fantasies that were inspired by her work and that draw the viewer into the fierce symmetries of their bizarre and creaturely shapes.

Featuring a range of photographic expression–from the anthropological to the poetic, from documentary to surrealism–Creatures Real and Imagined expands the range of animal photography beyond the sentimental, demonstrating again Salzmann’s uniquely resourceful genius as a photographer.

“Creatures Real and Imagined” closes on April 30, 2022. Art on the Avenue, 3808 Lancaster Ave