NEWS

Artblog coming attractions

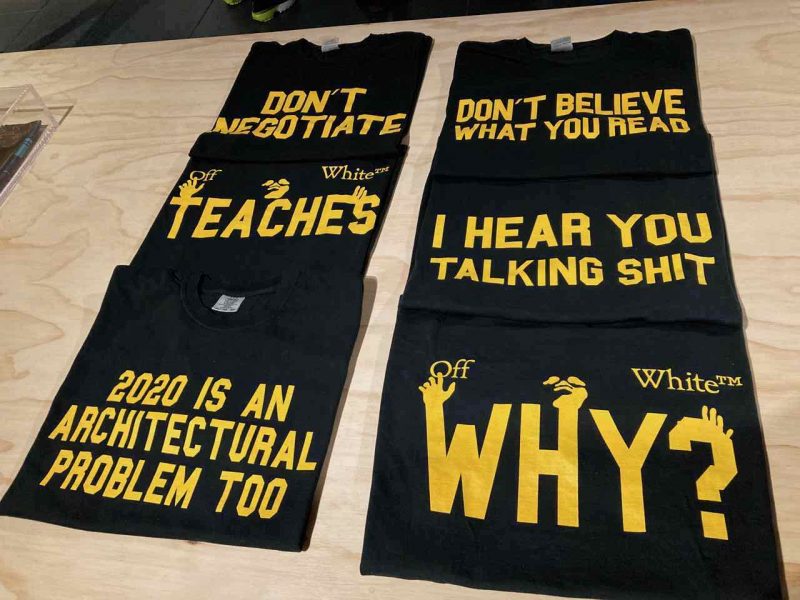

Coming soon, Roberta’s quick hits from a recent New York trip, including close encounters with the Duke Riley and Virgil Abloh exhibits at the Brooklyn Museum and powerful paintings by Robert Colescott at the New Museum.

Also on tap, from Tasso Hartzog, an interview with comics artist Nick Bunch of Reptile House Comix, from Alex Smith, a lively interview with James Dillenbeck, whose art brings to life the “Black Vans” characters authored by Smith in their comic book series by the same name. And three upcoming podcasts: with the Goggleworks Summer Artists in Residents; with rod jones ii speaking with Logan Cryer; and with Pedro Ospina, artist and founder of Open Kitchen Sculpture Garden.

Finally, come back soon for a quick look at Jayson Musson’s “His History of Art,” at the Fabric Workshop and Museum. Musson, an Artblog favorite (listen to Artblog’s 2011 podcast), who made a big splash with “Art Thoughtz,” his snarky YouTube art history lessons delivered by Jayson as the hip hop truth-to-power character, Hennessy Youngman. As much as Musson’s new art history video series delivers snarky commentary, the snark doesn’t come from Jayson, or, “Jay,” the character he plays, but from his raunchy sidekick, the Hennessy Youngman-like puppet, Ollie. More to come, stay tuned.

EVENT

Public engagement event for citizen input on the Roundhouse Project

Thursday, August 4, from 1-5 p.m.

Franklin Square at 200 N 6th Street (across the street from the Roundhouse)

Learn about the Project, Meet the Project Team, Snacks, Music and Art Making

The City announced today an event on August 4 as part of the ongoing Roundhouse community engagement process which will help the City understand how Philadelphians feel about the future of the former police headquarters. More information about the Roundhouse Futures project here.

This event, called Framing the Future of the Roundhouse, will be an opportunity for Philadelphians to share their feelings on the future of the site before it is put up for sale in 2023.

The event will take place on Thursday, August 4, from 1-5 p.m. in Franklin Square at 200 N 6th Street. The square is across the street from the Roundhouse. The event is hosted by Connect the Dots and Amber Art & Design, the consultant team behind the creative public engagement effort. For more information about the project and further opportunities for engagement,

Philadelphians may visit the Roundhouse project website. To stay up to date on other Framing the Future of the Roundhouse events, residents can sign up to the project’s newsletter.

About the Framing the Future of the Roundhouse Project

Framing the Future of the Roundhouse is a yearlong project to understand how Philadelphians feel about the former police headquarters. The results will guide the terms of sale for the building. The team behind the project is Connect the Dots and Amber Art and Design. They use a process called Meaningful Placemaking, which centers the community as the most important designers, users, and valued voices for a project.

About the Roundhouse

Designed in 1959 and dedicated in 1963 as the Philadelphia Police Administration headquarters, the Roundhouse is located at 7th and Race Streets. The building is nicknamed the Roundhouse for its unique shape and heavy concrete form. For many, the building is a reminder of police brutality. For others, the building is iconic. Development of the site must balance the City’s need for financial return with the principles, concerns, goals, and guidance from the public.

CURL UP AND READ

From The New Yorker magazine (Read it here.)

Can an Artists’ Collective Repair a Colonial Legacy?

In “Fertile Ground,” Alice Gregory travels to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where she reports on the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League, an artists’ collective established in 2014 with grand, sometimes surreal-sounding ambitions. The C.A.T.P.C., as the collective’s initials are rendered in French, is made up of some thirty local artists of all ages, who create figurative sculptures using river clay, which are then scanned in 3-D. The files are sent to Amsterdam, where they are cast in chocolate. The finished sculptures are sold in art galleries, mostly in Europe. With the proceeds from their art work, and with help from a European nonprofit, the coöperative buys back land—more than two hundred acres so far—and farms it using ecological methods, to replenish soil devastated by Unilever’s monocultural farming techniques in the region. The collective has built a museum called the White Cube. “If a museum can create a whole economy around it in London or in New York City, then it could do the same thing on the plantation,” Cedart Tamasala, a young man from Lusanga who is a founding member of the C.A.T.P.C., said. “The goal is to change this reality that has been imposed on us for decades—on us, on our parents, and on our grandparents.”

Renzo Martens, a forty-eight-year-old white artist from the Netherlands, refers to himself only as a humble servant or an administrator of the collective, but it was he who facilitated its creation, with the prominent Kinshasa-based environmentalist René Ngongo, and who helped to devise its early economic and artistic strategy. Though the collective now runs largely independently of him, he remains its interpreter to the Western art world. Gregory writes, “Martens’s work proposes that capitalist tools—selling art, buying land, establishing museums—can be used for anti-colonial ends. But is eliciting and then peddling the creativity of an impoverished population just another form of extraction economics? Can we exonerate vanity and pretension if they improve the lives of the poor?” Martens, whose actions, he insists, are peripheral to the work being done on the plantation, acknowledges the controversial nature of his role. With money brought in by the project, people eat more, and better. Houses have been repaired. The White Cube itself has created jobs: it needs to be maintained and guarded. Gregory writes, “The questions to be asked of the project are the same ones so often posed to the Western governments and corporations it seeks to criticize: Are Martens’s interventions effective? Sustainable? Will they create dependency? How will he withdraw, and when, and what will happen once he’s gone?”