and Da Vinci Art Alliance

When David Acosta, curator of I Look at the World, first conceived of a joint exhibition of photographs by Ada Trillo and Isaac Scott, he considered calling it The Summer of Our Discontent, a nod to Shakespeare’s Richard III. It seemed like an apt title—many of the images on display were made during the tumultuous summer of 2020—but it was too “up here,” he told me, gesturing with his hands towards the sky, too far removed from the show’s painfully real subject matter. In Scott’s images, that’s the Black Lives Matter protests that erupted in Philadelphia in the summer of 2020; in Trillo’s photographs, it’s the perilous northward journey of Central American migrants seeking asylum. “Discontent” was certainly not the right word.

Acosta instead found inspiration in a poem by Langston Hughes that connects the two photographers’ work with stirring language about race, borders and revolution. “I look at the world,”it begins, “From awakening eyes in a black face—/ And this is what I see:/ This fenced-off narrow space/ Assigned to me.” This stanza, along with the second, which declares that the walls of oppression “will have to go,” is inscribed alongside the images in the gallery. Just like Scott and Trillo, who hadn’t met before Acosta introduced them, Hughes’ poem—with its themes of eyes, walls, and oppression—was a perfect match for the exhibition.

Acosta worked for six or seven months to sort through hundreds of images for I Look at the World, on view until August 17 at Da Vinci Art Alliance and available as a video walkthrough. From those hundreds, he selected twenty-two. One photograph by each artist is printed in color, and the rest are black and white.

In Scott’s only color photograph, orange flames billow from a police cruiser, their glow reflected in the wet pavement. Standing up close, you can nearly feel the waves of heat. It is the first image I saw when I walked into the gallery, and it has a magnetic power that is somehow unique among the dozens of other photographs of burning cop cars I saw during the summer and fall of 2020.

Originally from Madison, WI, Scott was working towards an MFA in ceramics at Temple’s Tyler School of Art and Architecture when the pandemic hit. He had recently taken a photography class and, in need of fresh air during those claustrophobic months, started walking around his neighborhood with a camera, recording whatever caught his eye.

Then George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, and when protests in Philly began five days later, Scott was there with his camera.

During those first weeks of protests, he shared his photographs on Instagram nearly every day. In early June, he received a direct message on the app from someone who claimed to be a photo editor at the New Yorker and said that the magazine would like to print his work.

His first thought was, “That’s not real.” After confirming that the person who sent him the direct message was, in fact, a New Yorker photo editor, he wondered, “Why was I the one chosen?”

The answer to that question is in Scott’s photographs, which were published in the June 22, 2020, issue of the magazine.

Acosta wrote in his curatorial statement that I Look at the World explores the role of the photographer not just as an observer, but as a “participant.” Key to Scott’s success is the fact that he was, in the words of the New Yorker headline that ran alongside his images, “on the front lines.” He wasn’t only there to document—he was there to protest, too. About his photography, Scott told me, “This is what I have to offer the movement.”

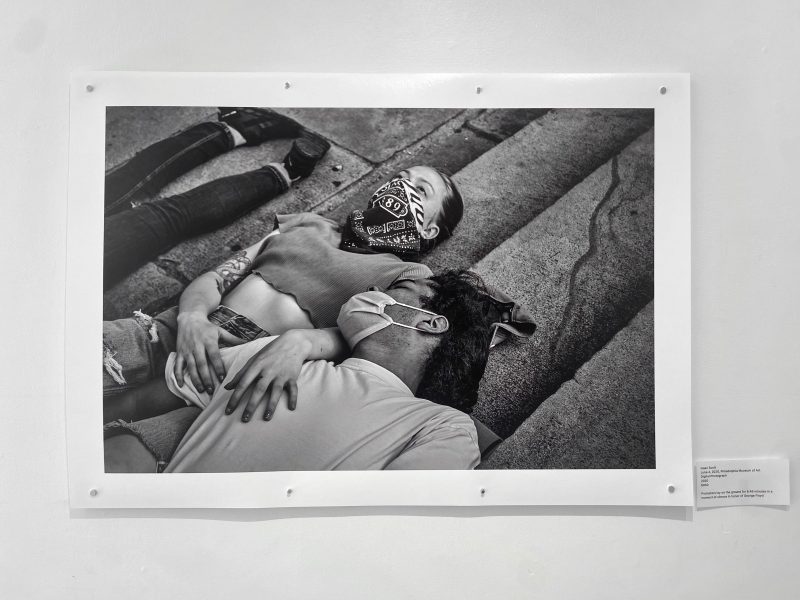

His closeness to the action and the trust that it engendered in his subjects allowed Scott to capture intimate moments that eluded other photographers. In one image in the exhibition, a protestor marches with hundreds of others down the Benjamin Franklin Parkway; her eyes, just visible above the top of a sign she’s holding, are fixed on the camera with a penetrating stare. In another, Scott observes two masked protestors lying on the steps of the Museum of Art, their limbs intertwined, one’s hands holding tenderly onto the other’s shoulder.

“I wanted people to see the humanity,” Scott told me. “I think it’s important that we tell our own stories, especially as Black and brown people.” He emphasized the significance of the historical record and the fact that his photographs, published in a national magazine, are now a part of it. “Isaac Scott, 2020,” might one day appear in the photo credits of a textbook.

That awareness of history shapes the exhibition: one image shows a march organized by members of MOVE that passed by the site of the 1985 bombing, which razed dozens of homes in West Philly and killed 11, including five children. The protests in 2020, the scene reminds us, were not an isolated movement. The rage was fresh but not at all new.

Cops, the objects of that rage, are generally sidelined in Scott’s images, appearing behind a wall of smudged riot shields, or as pairs of arms and legs wrestling a protestor to the ground. One exception is a photograph of three National Guard troops stationed outside the Municipal Services Building. One of them—hands draped over a riot shield, automatic rifle slung behind his back—looks very bored. He seems to be looking at the camera, and it’s tempting to imagine that behind his sunglasses he might be thinking, “Why am I here?”

Da Vinci Art Alliance

The police are present more often in Trillo’s section of the exhibition, even when they aren’t actually in her photographs. When you see a migrant named Joel crossing the Suchiate river between Guatemala and Mexico, holding a pair of crutches above his head, you understand that the desperation in his face is driven by his fear that law enforcement might enter the frame.

Complicating the familiar narrative, Spanish is the only language that appears on the uniforms in Trillo’s photographs: “policía federal,” “guardia nacional,” “marina.” Even when the migrants are within a few hundred feet of the U.S. border, it is Mexican federal police and not U.S. Border Patrol agents who block their path. As Acosta told me, Trillo and Scott “have a common language,” and their work is most powerful when taken together. Scott’s photographs hang on the right side of the gallery, and Trillo’s face them on the left. A phalanx of riot shields in West Philly on one wall mirrors a very similar phalanx of riot shields in Mexico on the other. The language on the uniforms might change, but police repression has no borders.

While Trillo’s photographs are deeply political, that doesn’t mean they aren’t personal.

“I think one of the most powerful images in the whole show is Ada’s image of the girl,” Scott told me, referring to “Maria Fernanda.” “It hits you hard. The humanity in that photo, in those eyes, is haunting.”

The portrait itself may be haunting, but the description beside it is shattering. Trillo explains that Maria, 15 years old and a member of the LGBTQ community, “was dressed as a young man to protect herself during her journey.” At the U.S. border, she was refused asylum and deported to Honduras. This year, Trillo reports, Maria was killed by gangs.

Trillo, based in Philadelphia but born and raised in Juarez and El Paso, had become friends with Maria while she traveled with a group of migrants towards Tijuana in 2018. Like Scott, she was not just an observer. She slept and ate alongside the migrants, earning their trust and encouraging them to drop their guard.

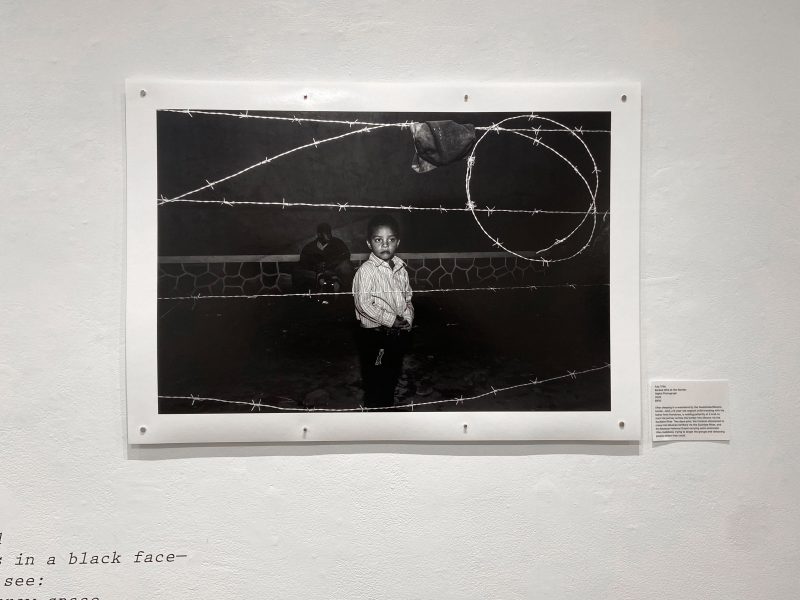

Trillo’s work is most moving when she brings children like Maria into the frame. In one photo, she shows a boy named José looking through strands of barbed wire. At six years old his eyes are still big and vulnerable, but he is dressed like an adult in a button-down shirt tucked into his pants. Childhood is a luxury not afforded to the likes of Maria and José.

On the way out of the gallery, I stopped again at Scott’s photo of the burning cop car, which is titled “October 26, 2020, 55th & Pine.” Along with a few other images in the exhibition, it was made in the days following the police killing of Walter Wallace, which reignited the anger that had fueled the summer’s protests—anger that intensified when it became clear that the largest mass protest in United States history had resulted in frustratingly little institutional change. “After Walter Wallace, that hurt the most,” Scott said. “It could’ve been prevented by the measures we were advocating for.”

I thought of “Harlem,” another poem by Langston Hughes that may be his most well-known today. It begins with a question—“What happens to a dream deferred?”—that Trillo, Scott, and Acosta also seem to be asking in I Look at the World: What happens if the police killings don’t stop? If the U.S. continues to refuse asylum to desperate migrants?

Hughes offers a few possibilities. Maybe the dream dries up “like a raisin in the sun,” he writes. “Maybe it just sags/ like a heavy load?”

“Or does it explode?”

I Look at the World, two-person show with Ada Trillo and Isaac Scott, Da Vinci Art Alliance, on view until August 17. See a video walkthrough of the show.