I spent a day at the Brooklyn Museum last week and was deeply impressed by the contemporary art programming. It was smart, pertinent to the times and the local audience, and indicative of a broad range of what’s going on. That’s in contrast to most museums, especially general survey museums which have only recently begun to exhibit contemporary work and stick to a very small number of artists who already have widespread reputations. Instead the Brooklyn Museum is mining the wealth of the artistic community of Brooklyn.

I’m not talking about the museum’s large exhibitions, such as surveys devoted to Virgil Abloh, or the upcoming Nellie Mae Rowe exhibition. They receive publicity, if not commensurate crowds. It’s the smaller exhibitions and projects that impressed me, especially those which include objects from the permanent collection.

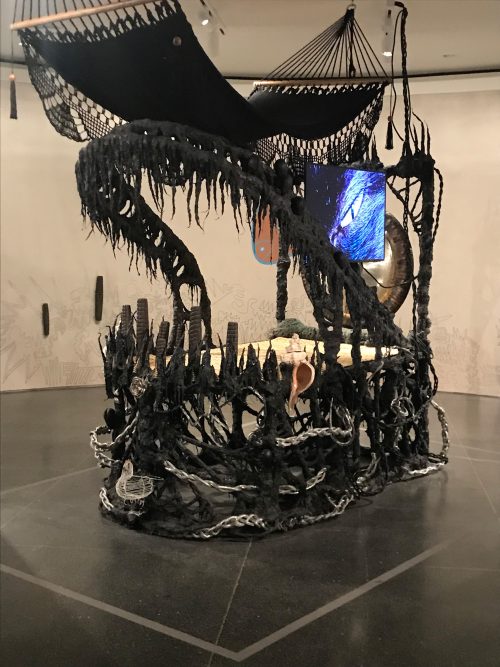

“Guadalupe Maravilla; Tierra Blanca Joven,” (through Sept. 18) is an exhibition devoted to healing. The artist came to this country alone, an undocumented 8-year-old child fleeing war in El Salvador. He became an artist and a healer and described his experience of cancer as an opportunity to learn. His artwork draws upon Mayan traditions, both recent and ancient, and the landscapes he traversed to reach New York. He worked with a professional painter of retablos – devotional paintings, as a way to tell his story, but has moved on to a series that incorporates healing sound with objects of personal and cultural meaning. Works he calls “Disease Throwers” include healing gongs with artifacts he collected when recreating his migration route: shells, loofahs, volcanic rock and discarded household objects. One is the size of a large bed where a person can lie while experiencing sound; its extravagant, organic forms are encrusted with objects. The exhibition includes a case of work from the museum’s Mayan collections, an eccentric flint and various ceramics, which had ritual use and became a means for the artist to understand his own cultural history.

Maravilla had worked with groups of undocumented people and cancer communities, but said the experience of Covid has left everyone with a need for healing. The exhibition was funded with a grant from the Wellcome Trust devoted to mental health, and the artist worked with a group of local adolescents to create their own healing environment in the gallery adjacent to his own work. Visitors are welcome to sit on large cushions in a tented space and to share their selection of helpful books. Art can perform many functions, and in selecting an artist interested in healing, the museum is relevant as well as is sensitive to the collective trauma of the moment.

Upstairs was Duke Riley’s sprawling “Death to the Living; Long Live Trash” (on view through April 23, 2023). The artist has accomplished a remarkable feat of creating socially-critical work that addresses a major, environmental problem and at the same time is remarkably engaging, funny and accessible to all. He doesn’t need to preach when he can demonstrate the extent to which industrial plastic has polluted our waters. The first room includes a hanging display of “Duke the Fisherman’s High Quality Fluke Rigs,” Made in the USA TM, a colorful display of fishing lures each of which resembles a small squid; they are constructed from plastic tampon applicators which the artist scavenged in Northeast coastal waters and on shores. A large video screen shows the artist adapting his found refuse as well as successfully using them to catch fish.

Other cases include his remarkable collection of scavenged plastic that he painted, virtuosically, to resemble scrimshaw – the bone and horn objects which sailors carved during long nights before radio and tv, and brought home to their loved ones. Riley’s creations betray their original functions by the recognizable shapes of household cleaners, detergent and Clorox bottles, catsup and honey dispensers and take-out coffee cups. The artist’s faux-scrimshaw designs also comment on the sources of their creation, distribution, and spread as non-biodegradable waste. They picture important names from the plastics industry, significant incidents in naval history, and contemporary landscapes such as the Gowanus Canal studded with floating refuse. The insole of a plastic, flip flop sandal pictures a swordfish with just such a sandal dangling from its sword.

The exhibition includes pertinent objects from the museum’s collection: actual scrimshaw, and also ceramic objects that reflect a history of craftsmen creating objects for both commemorative and satirical purposes. An early, 19th century jug commemorating George Washington sits next to Riley’s plastic, take-out coffee cup decorated with an image of an eagle whose shield reads “PET” for Polyethylene Terephthalate, the plastic most commonly used for containers and bottles. In the case beside it Riley’s plastic honey dispenser, decorated as a bear with fish in its stomach, sits beside a jug depicting President McKinley dressed as Napoleon, as a way of criticizing his imperialist activities in the Philippines. Such comparisons not only situate Riley’s work within an historical context but also make otherwise obscure parts of the museum’s collection interesting and accessible to new audiences.

On the way to the Riley exhibition I encountered a vase which the museum had commissioned from Robert Lugo sitting next to the work that inspired it: Karl H. Mueller’s design for Union Porcelain Works, the extravagantly-ecclectic “Century Vase” (1876), which includes George Washington’s profile and scenes of industry, farming, trade and peaceful encounters with Native Americans. Lugo’s “Brooklyn’s Century Vase” (2019) depicts a considerably less whitewashed view of the borough’s history, including not only the Brooklyn Bridge, but also Jackie Robinson, ordinary young men in hoodies and illustrated food stamps.

Another chance encounter, beside a ground floor elevator, were five 30-second videos, commissioned in 2021 by the museum in partnership with MTV. The artists were Nicholas Galanin, Christine Sun Kim, Tourmaline, Ja’Tovia Gary, aka JA’TAAAVIA aka Jah Jah, and John Akomfrah. It was the most interesting possible wait for an elevator.

Duke Riley, ‘DEATH TO THE LIVING, Long Live Trash, June 17, 2022 – April 23, 2023, Decorative Arts and Design Galleries, 4th Floor, Brooklyn Museum of Art, 200 Eastern Pkwy, Brooklyn, NY 11238