Every city has its architectural oddities. As industry and technology accelerate and styles change apace, a handful of atypical structures endures in even the most rapidly evolving urban environments. Standing strong against the ebb and flow of time, these buildings resist gentrification and other urban renewal projects. Their initial functions, however, tend to alter. Living several lives, they adapt as new circumstances arise, all the while retaining their original style and native charm. Weathering the storm of perpetual urban flux, these oddball buildings hold a special place in my heart.

Several such structures exist in Baltimore. A post-industrial “Rust Belt” city whose population doubled by the mid-20th century only to dwindle to almost half its pinnacle in the postwar era by the turn of the 21st, Baltimore has seen better days. While the many contributing factors to such population decline are disconcerting, to say the least, the silver lining is that Baltimore’s most antique and unique buildings aren’t lost to “progress” too soon. Some of its most distinctive structures continue to stand in the face of complex socio-economic changes. Though their original purposes have altered, they retain their original look. While considering the above, five such buildings in Baltimore come to mind.

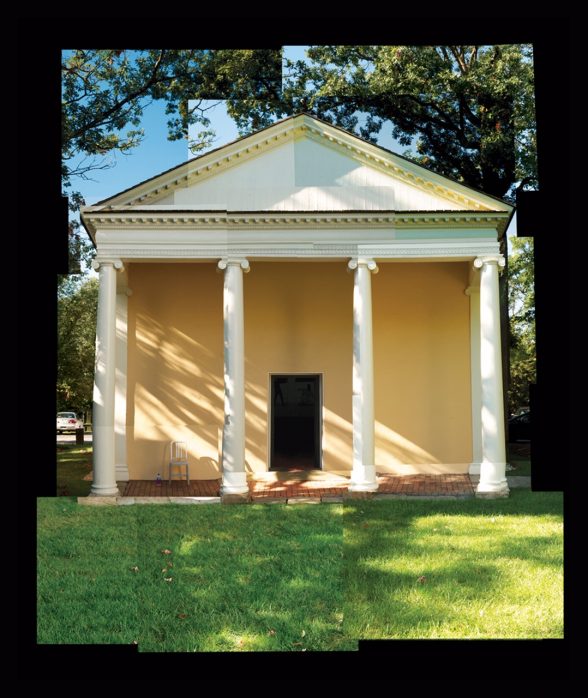

The Spring House, or Dairy

Baltimore Museum of Art

The Spring House, or Dairy, on the west lawn of the Baltimore Museum of Art is the perfect example of an architectural anomaly whose original function has been updated to fit current needs. This Greek Revival structure is the oldest in my round-up, and also the only one to have been relocated. Designed by the British-born Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “father of American architecture” and President Thomas Jefferson’s architect for the United States Capitol, the Spring House was originally used as a dairy. Essentially, it was a large walk-in refrigerator over a century before the invention of electric cooling. Eggs, milk, and other perishables were stored inside the Spring House to keep cool via a small spring flowing beneath it. Special vents in its walls could be angled to capture cool air rising from the bubbling water below.

Like Latrobe’s U.S. Capitol building, the Spring House was built by slaves. It was first located on Robert Goodloe-Harper’s country estate, a former plantation in what is now the affluent Roland Park neighborhood of Baltimore. The Spring House was moved to its current location on the grounds of the BMA in 1931 and remains one of the largest artifacts in the museum’s collection. It was briefly used as a gallery showcasing 18th- and 19th-century architectural elements, most of which are now on view in the BMA’s American Wing. More recently, the Spring House has become the site for contemporary art installations and video screenings. In 2019, its interior room served as the exhibition space for Oletha DeVane: Traces of the Spirit, in which the local artist reimagined the dairy as a sacred altar. Redubbed as the Screen House during warmer seasons, the Spring House has been used as a screening room for music videos by local talents such as TT the Artist.

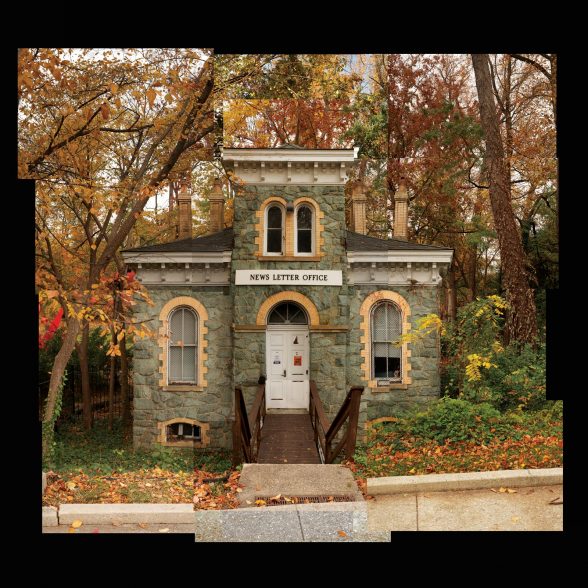

The Wyman Estate Gatehouse

Johns Hopkins University

Just a little east of the Spring House, at the corner of Art Museum Drive and Charles Street, in the southeast corner of the Johns Hopkins University Homewood campus, quietly sits a fanciful little building like something out of a dream. The Wyman Estate Gatehouse, a two-story Italianate structure made of a green stone called serpentine and white trim would look right at home in a Wes Anderson film. Indeed, along with the Rawlings Conservatory at Druid Hill Park and the Peabody Library, the Wyman Estate Gatehouse is listed as one of three Baltimore locations on the Accidentally Wes Anderson website.

In the 19th century, wealthy Baltimore philanthropist William Wyman donated his estate of 179 acres and $1 million to help establish Johns Hopkins University. The Wyman Estate Gatehouse, originally known as Homewood Lodge, is the only remaining building from the Wyman Estate; the residential mansion, Homewood Villa, was demolished by the University in 1954. Though the mansion is lost, the Gatehouse lives on. It’s been well-preserved and well-used over the years, having served as the meeting site for several scholarly organizations. Since 1965, the Gatehouse has been the official home of the Johns Hopkins News-Letter, one of the oldest student-run college newspapers in the nation, the first edition of which was published in 1896. While I was reading a sign about its history outside of the Gatehouse, an older passerby told me she often smelled pot smoke blowing out of its windows in the 1960s and 1970s.

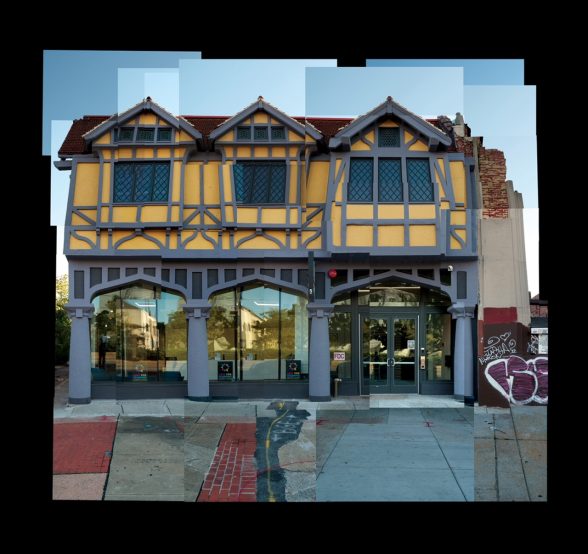

Odell‘s Nightclub

Station North Arts District

A mile south of the Gatehouse, a former dance club recently began a new life as an art and technology center for city youth. Odell’s Nightclub opened on North Avenue in 1976 and became one of Baltimore’s premier disco clubs until its closure in 1992. Though criticized by some as a source of crime in the area, “Odell’s was hugely popular and is still revered by some as the heart of house and dance music in Baltimore in the 1980s.” After it was shut down for good in the early 1990s, the old nightclub sat dormant for almost two decades. Its first floor was boarded up and covered over with graffiti and orange construction netting; its second-story windows were removed and the whole level painted over in a sickly yellow. Thankfully, its charming, Tudor-esque facade was preserved. Even in a state of decay, the peculiarly medieval face of Odell’s stood out from the more modern storefronts that run along North Avenue.

More recently, the abandoned nightclub was renovated to provide a new home for what is planned to become an “arts and technology hub” in Baltimore City. Two non-profits, Arts for Learning Maryland and Code in the Schools moved into the space earlier this year. With the recent renovation of other historic buildings nearby, such as the Parkway Theater, the neighborhood is really beginning to live up to its new name as the Station North Arts District.

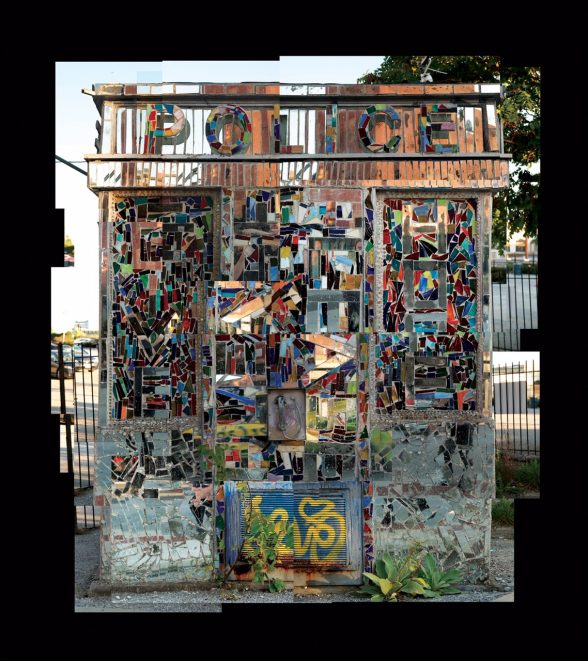

Police Box

Station North Arts District

Just around the corner from the nightclub cum media lab, stands a curious site at Charles and East Lanvale. This edifice is less a building and more of a monument. But to what? Or for whom? Fragments of multi-colored mirror and other shiny items were meticulously affixed to what appears to be a former Baltimore police box. Baltimore used to have a bunch of these police or “callboxes” strategically placed around the city. Phones attached to their outer walls allowed the public to make emergency calls from them, while their interiors were used for cops to monitor the area, take breaks, or even hold detainees until backup arrived. The Baltimore police boxes were based on the British version, like the one used in the TV series Doctor Who.

Local artist Loring Cornish created “Change for the Better” a few months after the protests and political unrest following Freddie Gray’s murder by police in April 2015. The installation’s four sides mirror its surroundings, fragmenting people and cars as they pass by it, briefly miniaturizing them within its myriad mosaic pieces. The box itself feels somehow dead, as if frozen in time, its lights snuffed out. It’s as though the mosaic exterior is some sort of invasive species that has taken over the host structure, literally reflecting the world around it.

You Are Here

East Baltimore

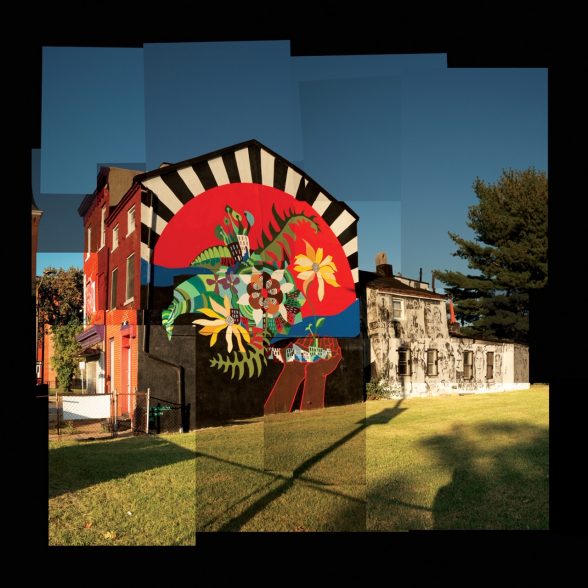

The fifth and final architectural curiosity I’d like to highlight is further afield than the rest. It’s also not a single structure, but more a complex of buildings. Several rowhomes including a corner cafe in East Baltimore, all of which have long since been abandoned, serve as the canvas upon which local street artists have applied their unique styles and talents. Curated by Baltimorean Yvonne Hardy-Phillips, You Are Here is a massive, collaborative mural project celebrating her neighborhood.

Hardy-Phillips grew up in East Baltimore and inherited her family’s properties at the intersection of Harford Avenue and Biddle Street in Johnston Square. She chose to keep the property instead of selling it. You Are Here was actually a graduate thesis project for her MFA in Curatorial Practice at the Maryland Institute College of Art where Hardy-Phillips graduated in 2017. Since then, her unique monument to the neighborhood where she and generations of her family grew up in, continues to stand, fostering a strong sense of place to an area that might have otherwise been obliterated by gentrification. Like Cornish’s police box mosaic, Hardy-Phillips’ You Are Here reimagines abandoned architecture as public art.

* * *

These five buildings, and many others like them, punctuate the built environment of Baltimore. Retrofitted for newer circumstances, they retain their inaugural looks while adding character to their contemporaneous surroundings. Over time, they learned new tricks: a dairy, built by slaves, becomes the exhibition site for contemporary art by African Americans; an old gatehouse, the last remnant of a long forgotten estate becomes the home of a student publication; a former nightclub morphs into a media lab for young creators; a police box is turned into a piece of roadside sculpture; and a collection of historic rowhomes is exalted to the status of a monument for a neighborhood’s rich culture and history. Perhaps these buildings will connect in other ways in the future. I could see Mr. Cornish contributing to Ms. Hardy-Phillips’ You Are Here; a video documentary of the process could be made by kids from Young Audiences of Maryland and later screened in the Spring House at the BMA; the Johns Hopkins News-Letter could then write a review. That exact scenario may be unlikely, but who knows? Stranger things have happened.

As the modern world changed all around them, these oddball buildings held on, adapting within while keeping a straight face without. Their perseverance suggests that while it may be prudent to keep up with the times, it is also wise to hold on to the best parts of the past.