It seems that 2022 is a year for examining the changing world of contemporary craft. First, a major American Institution, The Renwick Gallery, which was founded as a museum to showcase American craft, has installed a large exhibition displaying many of its new acquisitions. When it opened in 1972, at the height of the studio craft movement when artists, who worked in what were considered craft media, were exploring modernism, these artists and their collectors were demanding serious attention. Works such as those by Laura Andreson, Toshiko Takaezu, and Rick Dillingham represented elegance and refinement in ceramics at that time. They demonstrated modernist abstraction and the kind of collecting that the Renwick has pursued. Fifty years later, the Renwick is looking closely at how their collection represents not only the history of American craft, but also the discipline today.

This Present Moment, organized from the Renwick collection by Mary Savig, the Lloyd Herman Curator of Craft for the Renwick Gallery, includes 171 works made by a diverse group of American artists with the more contemporary objects having been recently purchased. Indeed, 135 of the objects in the exhibition at the Renwick Gallery are new acquisitions and on view for the first time. According to the museum, with this exhibition the museum is introducing contemporary artworks that push the boundaries of the handmade, recognizing new ways to make objects by hand in the 21st century. It is not the first time they have done so. In 2013, 40 under 40: Craft Futures suggested an expanding definition of craft that includes sculpture, industrial design, installation art, fashion design, sustainable manufacturing, and mathematics. The borders between media and disciplines have largely dissolved and technology has entered the field, as have conceptually based art practices, long associated with sculpture and installation art.

Alicia Eggert’s This Present Moment, a neon and steel installation, demonstrates this contemporary outlook. Eggert states in the exhibition catalog: “I consider myself a conceptual artist, but I don’t think ideas alone are ever enough. I like to give language physical, material forms. . .”* Many artists today are committed to beginning a work with a concept. Some are devoted to a particular medium while doing so, but others feel comfortable exploring a range of media. Susie Ganch’s Drag is composed of collected debris, mostly discarded plastic and metal. On an exhibition label, Ganch stated, “Our collective detritus connects me physically to the world outside my studio while also serving as a commentary on our collective habits of consumption.” The form is a monumental bracelet, which shows off her metal and jewelry skills while working within a conceptual framework.

Other works in the exhibition address political and social issues as well, including L.J. Roberts’s brightly colored, mixed-media fabric mapping of queer community building in Brooklyn, New York, The Queer Houses of Brooklyn in the Three Towns of Breukelen, Boswiyck, and Midwout during the 41st Year of the Stonewall Era. Similarly, Tanya Aguiñiga’s Metabolizing the Border, a performative work is represented in This Present Moment by an extremely large photograph of her walk along the border fence wearing a suit that the artist made to demonstrate the physical and psychological experiences of migrants. The leather and neoprene wetsuit, also on view, includes an analogue VR headset and a fence fragment embedded with glass. Consuelo Jiménez Underwood’s Run, Jan, Run!, a weaving that contains barbed wire and caution tape, addresses the United States-Mexican border. Consumption, immigration, identity, Covid, and racism, among other urgent problems, have entered the craft field. Bisa Butler’s monumental quilt Don’t Tread on Me, God Damn, Let’s Go! — The Harlem Hell Fighters brings together an historical event with African American quilting traditions in a compelling and complex composition that calls out to viewers, with a presentation of the members of the 369th Infantry from World War I, who received highest honor from France but then experienced tremendous racism when they returned home to the US.

While the Renwick presents many different craft media, other institutions are focused on specific media, especially glass this year, as the United Nations General Assembly has declared 2022 the International Year of Glass. The Delaware Contemporary in Wilmington has devoted the lobby and six galleries to it. “Through a Glass Darkly,” curated by a team of three artists/educators, Kristin Deady, Jenna Lucente, and Alexander Rosenberg, concentrates on conceptual approaches. Rosenberg explained in an email that they were all colleagues at Salem Community College when they began working on the project. Lucente is a resident artist at the Delaware Contemporary. She wrote in an email to me that In early 2020, she proposed the idea of a large-scale glass exhibit to Leslie Schaffer, Executive Director of the Delaware Contemporary, who was very open to the idea. The curatorial process they employed is one that many contemporary curators use—contacting some artists whose work is known, here labeled anchor artists, Bohun Yoon, Helen Lee, Kristen Neville Taylor, and David King, and then holding a juried open call to find others. The result at Delaware Contemporary is an extremely ambitious exhibition of 36 artists.

The works in the show are not what many people imagine for glass art. Most think of vessels, vases, and possibly the sculpture of Dale Chihuly. In an email, Lucente explained to me that Rosenberg and Deady were instrumental in shaping the theme – that glass can supply and deliver both information and misinformation equally. For Rosenberg, the theme came from an article he read in late 2020, “Towards a Cultural History of Plexiglass,” by Shannon Mattern. He stated that he admired the idea of framing a current cultural moment, and the history leading up to it, through the lens of a particular material, which has been integral to society since its inception and remains a part of new technology today. Rosenberg was also reading the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard and critiques of him which addressed how our vision of reality is imperfect, an idea that is derived from 1 Corinthians 13:12 in which the Apostle Paul states, “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.” (King James version). Some other translations have used the word mirror rather than glass.

Rosenberg further related that the duality of glass, that is to have both a clear and an obscured vision, led to the title of the show. Moreover, he and Deady have had a long-standing interest in optical devices. The curatorial statement explains: “Selected works engage the historical promise and power of the material to reveal and to bring clarity, while challenging viewers to acknowledge an inherent interconnectedness between enhancement and distortion.”

With so many artists, it helped the exhibition’s unity that the curators divided the show up into themes: Body, Environment, Systems, Ancestry, End-Of-Days, and Perspective, in which there are many standouts. David Kings’ Echo (Index), a brightly colored installation found in the lobby, demonstrates some of the various glasses or glass related materials, such as float glass, plastic, and silicone. The work, King elucidated on the exhibition label, references anamorphic Baroque stage sets, those that had specific viewing places, with the monarch having the best seat in the house. These sets demonstrated 17th century artists’ ability to create illusionistic special effects. As you move around King’s installation you notice different elements at changing positions. The bright colors help to emphasize the various points of view.

Helen Lee’s Implosive and Incendiary is a dramatic installation that again demonstrates differing materials, here glass, matches, and wire rope. Lee explains that this work addresses the collapse and expansion of time as it connects to the burden of inherited racial histories of immigrant Americans. One source for this work is Prince Rupert’s drops which are produced by dropping molten glass drops into cold water. The water rapidly cools and solidifies the glass from the outside inward producing a tadpole-shaped droplet. The other inspiration is Tar Pitch drops, which seem solid at room temperature but actually are a fluid that drops extremely slowly. Together, these two types of drops represent different amounts of time.

Rebecca Arday’s In Situ No. 2 presents an extremely witty object, a small blanket or throw that rests on a found chair/desk. The throw is made of graphite on dura-lar film. The found chair harks back to such well-known works as the conceptual One and Three Chairs, 1965 by Joseph Kosuth and Rene Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (This is not a Pipe), 1929. The blanket’s drapes appear soft but they are not. And finally, the title tells us the work is in position, in its intended spot, as in situ is used in art history to let us know a sculpture is in its intended or original location. However, it is really the blanket of dura-lar that is in position on the chair, which can be moved, while the dura-lar appears permanently situated due to its delicacy. Finally, the cast shadow indicates the object is real which reinforces the title.

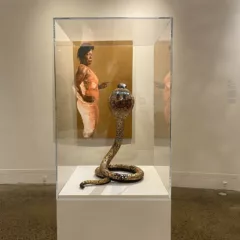

Another exhibition related to the year of glass is Ex-tend Ex-cess at Towson University’s Center for the Arts which I co-curated with Sagi Refael from Los Angeles. This show too explores expanded definitions of craft. There are thirteen artists in it, all working in clay, sometimes along with other materials. An exhibition of contemporary abstraction, it explores compositions and forms that demonstrate additions, growth, combinations, excess, exits and entrances, and endings and beginnings — as extensions of the artists’ bodily gestures and conceptual ideas. It includes the work of such well-known artists as Matt Wedel, Zemer Peled, Sara Parent-Ramos, and Brie Ruais. If you can’t make it to Towson, there is an online tour on the gallery website as well as images of individual works.

The opportunity to explore so much art that investigates concepts, materials, and processes, often in unexpected ways, is rare. Spend a weekend discovering fascinating work, either traveling from the north to the south or visa versa. Towson sits in the middle between Philadelphia and Washington D.C. Each exhibition offers the opportunity for the viewer to spend time with the works, possibly going back to visit again and again to the institution nearest to you. You will not be disappointed.

*Alicia Eggert, “Artists Reflect,” in This Present Moment, Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2022, p. 115.

This Present Moment: Crafting a Better World

May 13, 2022 — April 2, 2023

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Pennsylvania Avenue at 17th Street NW

Through A Glass, Darkly

The Delaware Contemporary

200 South Madison Street

Wilmington, DE 19801

September 9 – December 31, 2022

EX-tend EX-cess: Metamorphosis in Clay

August 26 – December 10 (closed November 22 – 27)

Center for the Arts Gallery

1 Fine Arts Drive

Towson University