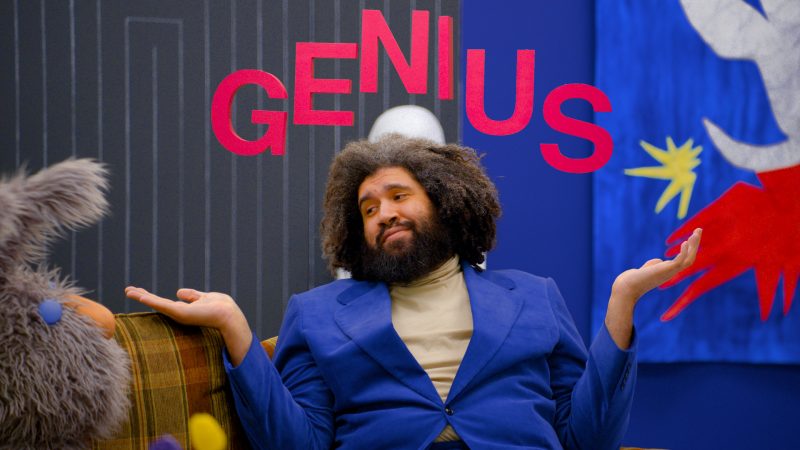

During the third and final video presented in His History of Art, Jay, a character played by Jayson Musson, breaks the fourth wall when he wryly states, “Look at the time. It’s out-of-money o’clock. We’ve spent the budget.” He directs this meta-commentary towards Ollie, a ragamuffin rabbit puppet voiced and controlled by Cedwan Hooks. Over the course of three episodes, Jay and Ollie explore art history in a play-world reminiscent of Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood and Pee-wee’s Playhouse. There are puppets, costumes, props, sets, actors, and of course, the labor of an unseen crew. Even with funding from Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, the money was bound to run out.

The humor of this line is not due to a budgeting issue singular to Fabric Workshop Museum or His History of Art. Jay’s breaking the fourth wall is funny because creative projects spend money the way water fills a cracked glass. This sort of wink-and-nudge towards the inner workings of the art world is at the core of His History of Art and will be familiar to those who have seen Jayson Musson’s previous work as Hennessy Youngman.

For the uninitiated, Hennessy Youngman was a character portrayed by Musson in a satirical vlog series titled, “ART THOUGHTZ,” which ran roughly from 2010-2012. The videos went viral and were loved by arts and culture nerds, especially arts and culture nerds in Philadelphia, where Musson lived at the time. Throughout the series, Youngman advises aspiring artists to brazenly take advantage of the art world’s prejudices in order to promote their own careers. “What’s another step in being a successful artist other than being a white man and/or woman,” Youngman considers in one video, “I say you should make your artwork ambiguous.”

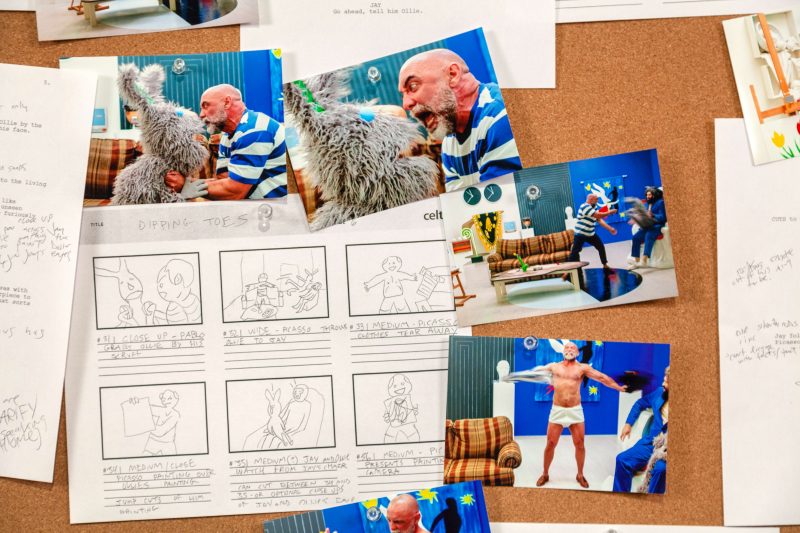

His History of Art, a solo exhibition by Musson, is promoted as an indirect extension of “ART THOUGHTZ.” There are new characters and an original narrative format. In each episode, turtleneck-clad Jay attempts to educate an apathetic Ollie on the relevance of art history in today’s world. In Episode One, Jay references ancient art to show Ollie how symbolism can impose and reinforce dynamics of power. Episode Two features a guest appearance from the “Venus” of Willendorf* (now usually referred to as the woman of), brought to life in a jaw-dropping, larger-than-life costume, who explains the role of desire in prehistoric art. The final episode contains a visit from Pablo Picasso, exquisitely portrayed by Andrew Criss, who admonishes Ollie for his quaint attempts at artmaking and instructs him to turn against Jay in an act of institutional defiance.

The three episodes, according to FWM, are inspired “from the structure and tone of educational programs such as PBS children’s shows and nun-turned-art critic Sister Wendy Beckett.” Where His History of Art falters is in its inability to employ the fundamentals of television writing, despite mimicking the format of a TV show. Who Jay and Ollie are as characters and what they mean to each other is not clearly established and yet the final episodes hinges on their troubled relationship. There is no clear thematic throughline between each episode—the title of the exhibition implies patriarchal critique, though it’s not a consistent topic. Especially when considering that the female character, who has the most lines, uses most of them to talk about her sexual body and the effect it has on men. The mature content, a pastiche of nostalgic television and short format that characterize the series is akin to the type of content found on Adult Swim. Noticeably, Musson’s videos fail to reach the same odd, vulgar or comical highs of its contemporaneous counterparts.

The gallery space that holds the exhibition contains three watching-rooms where each video is projected onto a wall and played in a loop. The close proximity of each viewing station causes overlapping sound; however, there are closed captions provided via QR code in each section for those who may need them. When exiting the final viewing room, viewers are suddenly face-to-face with the set where each episode was filmed. It’s almost a magic trick to see something from the screen appear suddenly in great detail. The set depicts Jay’s apartment, which is filled with art historical kitsch objects: a draped and hanging carpet designed after Dali’s “Persistence of Memory;” a fabric banner that depicts a racialized take on Matisse’s “Icarus;” and two minimalist clocks that sit next to each other à la Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled (Perfect Lovers).”

Beyond the set is a complete behind-the-scenes look at the production process for His History of Art. There are audition tapes, outtakes, costumes, additional set pieces, storyboards, and puppets displayed on pedestals and within vitrines. The exhibition text describes each item and gives a brief educational lens on how such productions come together. Viewers can learn how a storyboard is created or see a time-lapse video of the set being built from start to finish.

This type of glance behind the curtain is typical for FWM, whose modus operandi is to assist artists in the specialized fabrication of new art pieces that are complementary to the artists’ existing practices. It then behooves FWM to highlight the specific labor of their studio staff. However there is a problem of overexposure in His History of Art—the more that is explained, revealed, and put behind glass, the more the exhibition feels like an amalgamation of technical approaches rather than an inspired creative process. Granted, inspiration is hard to quantify. Viewers will likely enjoy the overall effect of Musson’s work, which is characteristically charming and intelligent, if not quite as focused and punchy as his previous endeavors.

*Editor’s note: Although traditionally and commonly known as the Venus of Willendorf, this figurine was made in an age we know more about than we did when it was found; however we cannot be certain of its purpose or meaning. Therefore we want to note that we agree with the art historians who have begun calling it the Woman of Willendorf as a way of removing an inaccurate and culturally specific reference from the figure’s name.