In the late 1990s, I attended one year of art school at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in Baltimore where it seemed like everyone I met had a tag. Tags are the cryptic, one-word pseudonyms graffiti artists scrawl across mailboxes, signs, walls and other surfaces around cities and towns. At art school in the ‘90s, they were de rigueur.

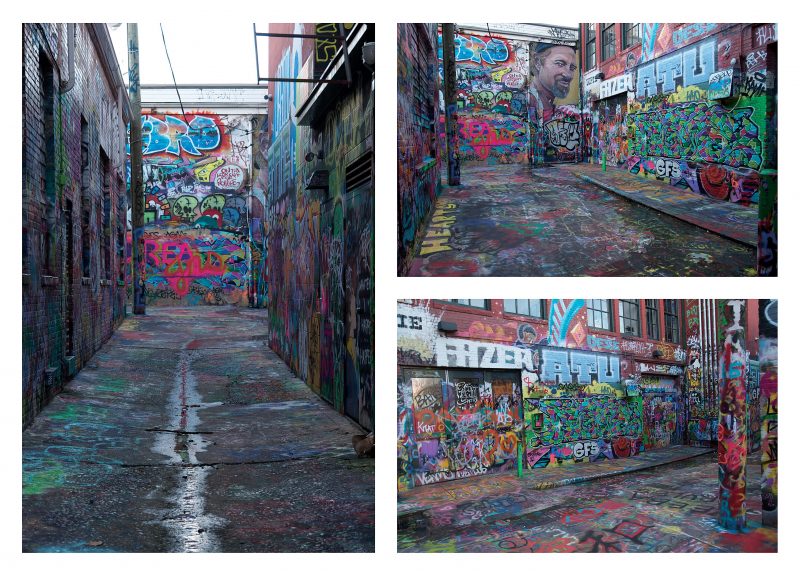

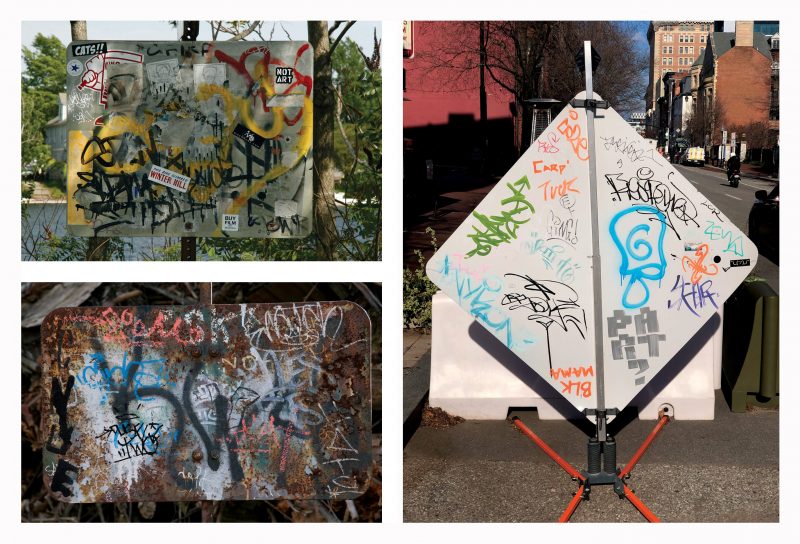

Tags are quick one-offs, made on the fly; fill-ins, slightly larger outlines of the same single-line word, filled in with two or more colors. Fill-ins tend to have a more bubbly feel to them. Pieces are the largest and most complicated designs that can fill up a whole wall with wild, interlocking compositions of cryptic scripts rendered in an array of vivid colors. The urban landscape is the graffiti artist’s canvas, both for sketching (tags) and for larger masterworks (pieces).

Why would anyone want to tag? It’s a way of announcing yourself to the world, that you exist, that you were there. It’s also political, a way of taking back the streets. But because it’s criminal, don’t use your real name when tagging. Choose a handle or nickname, ideally one not too long or polysyllabic, as you’ll need to get your word up quickly and be gone. Taggers often work in small crews so one can watch for cops while others go to work on a freshly painted wall.

The media of choice among most writers are spray paint and oil-based markers. Writers will also make prefab tags, known as slaps, writing their words on U.S.P.S. and “Hello, My name is…” stickers before going out to bomb. A writer might have on their person, while prowling the streets for fresh surfaces to tag, several oil-based markers of various colors, a few prefab stickers, a can or two of spraypaint, and a range of nozzles for different line widths.

Writers may also carve their words onto surfaces using a small blade, glass cutter, or other sharp stylus. Some writers incise their tags into the backside vents of air-conditioner units protruding out of apartment windows. This particular practice harkens back to graffiti’s ancient roots. The Latin root of “graffiti,” graffio, means “a scratch or scribble.” Inscriptions and figure drawings by common people have been found on the walls of ancient ruins such as the Catacombs of Rome and at Pompeii. The history of graffiti art is long and complex.

As you might imagine, innovations in this ancient art form abound at art school. My MICA schoolmate known as E-3, who chose this succinct configuration of characters for its sci-fi quality and graphic symmetry, liked to use plastic condiment bottles filled with paint to splatter his tag on the ground à la Jackson Pollock. In my one year there, E-3 got many ups in the Bolton Hill area around MICA. In fact, I recently came across one of his splatter tags on a sidewalk near campus just the other day. That E-3 is now a quarter-century old. The best writers choose places where their words will last a long time.

Photographs by Dereck Stafford Mangus

After completing my freshman year at MICA, I traveled around the United Kingdom, working odd jobs here and there in England and Scotland. Like Baltimore, London and Edinburgh were awash with graffiti art in the late 1990s, as I’m sure they are still. Upon returning to the States, I relocated to Boston and began working at an art supply store in Cambridge where I met another writer. Noise went bombing all over Boston and Cambridge, but stuck to the more popular spray paint cans and oil markers. Noise first introduced me to the work of Shepard Fairey, creator of the ubiquitous “Andre the Giant Has a Posse” / OBEY sticker campaign, begun by Fairey while an art student at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence. Fairey would later become renowned for his iconic Barack Obama “Hope” poster from 2008.

Though a big fan of his work, Noise was adamant that Fairey is not a graffiti artist. To Noise, graffiti stands apart from other forms of street art. Graffiti artists tend to put up words (and only sometimes images) while willingly breaking the law, whereas street or guerrilla artists tend to employ more graphic imagery (perhaps accompanied by text) in the form of wheat-pasted posters and stencils, and may or may not break laws doing so. Banksy is perhaps the most famous street artist worldwide (even though nobody really knows who they are) but still not a true graffiti artist as they don’t tag.

Fairey certainly has street cred as he does, in fact, break the law, putting up his politically-inspired posters. But like Banksy, Fairey is not a tagger and is therefore not a true graffiti artist. Taken as a whole, street art represents a vast and complex ecosystem, in which the graffiti artist is but one of many species among muralists, stencilers, wheat–paste posters, and yarn bombers. A hard hit up sign by several generations of taggers and other street artists may morph over time into a piece of urban pop art, an ever-changing palimpsest of colors and lines, pictures and words, stickers and tags.

Photographs by Dereck Stafford Mangus

Many famous artists started off doing graffiti. Before befriending Andy Warhol and becoming an art world darling in the mid-1980s, Jean-Michel Basquiat was part of the tagger duo SAMO (“Same Old Shit”) with Al Diaz, who got up all over Manhattan’s Lower East Side in the late 1970s and early 1980s. And Keith Haring scribbled his playful figures advocating safe sex and HIV/AIDS awareness on New York City subway walls around the same time. But even before Basquiat and Haring, there were TAKI 183 and Julio 204, two of the first postwar graffiti writers to tag in New York. [Ed. Note: See Artblog’s 2016 review of “Wall Writers,” the acclaimed documentary about graffiti featuring TAKI 183, Philly legend Cornbread and others.]

Further back still, there was the moniker (a.k.a.: hobo art, streak, or tag), a unique form of graffiti left by freight-train hoppers that began in the late nineteenth century. The moniker tradition on freight train cars from the 1890s anticipates the tagging of subway cars nearly a century later, in east coast cities like New York and Philadelphia when graffiti art became strongly associated with the burgeoning hip hop scene of the late 1970s.

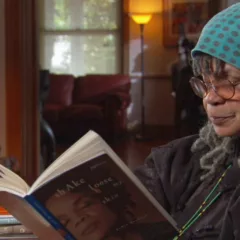

It’s important to emphasize contemporary graffiti’s strong connection to hip hop and how the two artforms have worked together to create a political force for working-class urban youth. As Brown University Chancellor’s Professor of Africana Studies Tricia Rose writes in her book on the subject, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America:

By the mid-1970s, graffiti took on new focus and complexity. No longer a matter of simple tagging, graffiti began to develop elaborate individual styles, themes, formats, and techniques, most of which were designed to increase visibility, individual identity, and status. Themes in the larger works included hip hop slang, characterizations of b-boys, rap lyrics, and hip hop fashion.

The influence of hip hop represents the latest chapter in the history of graffiti. Styles may have changed; new tactics and tools developed. But graffiti’s core impetus remains intact: the unsanctioned, illicit expression of everyday people often as an affront to the status quo.

* * *

Along with many cities around the world, Baltimore experienced a sharp uptick in tagging during the quarantine due to Covid-19. With schools closed and activities limited, all of a sudden kids had more free time on their hands. While this was to be expected to a certain degree, some taggers went wild. One word kept appearing in my neighborhood over and over: Kobe. Kobe. Kobe.

Kobe–whether beef or Bryant, I have no idea–is what my writer friends would call a toy back in the day. A toy is a writer who may be good but has no respect for the game. They tag indiscriminately, blowing up spots, cutting into other writer’s territory. The more thoughtful writer will find a spot that is visible but not too obvious, somewhere in the cut. The idea is to get noticed but not be hot.

Photograph by Dereck Stafford Mangus

A toy is hot. They lack vision. While it’s good to be bold with tagging, you don’t want to be so bold that your work gets singled out and removed too soon, sandblasted off or painted over by angry homeowners. This is exactly what happened to Kobe. Instead of sticking to the best spots for sustainable tags–abandoned buildings, back alleyways, dumpsters, overpasses, postal boxes, the backs of signs–Kobe hit up the facades of fancy residential buildings, parked cars, and walls that were clearly destined to be covered over by new construction. In other words, Kobe’s excessive bombing was pointless. Other than pissing off a few people and the local preservation society, Kobe proved nothing and was soon forgotten, his words erased from the district as the quarantine lifted.

Perhaps I shouldn’t assume a “he” when referring to Kobe. For all I know Kobe is a “she” or a “they;” a tag could be shared by a group of writers. And why “Kobe”? Kobe may have been a reference to the famous basketball player who died in a helicopter crash shortly before the pandemic arrived and the quarantine began. A friend of mine on the Baltimore City Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation told me that Kobe came up during one of their Zoom meetings last summer. A stern committee member intoned, “Whoever they are, Kobe is in a lot of trouble.” I never found out what happened to Kobe. But their work is long gone.

* * *

Etched into ancient walls at sites like Pompeii and spray-painted across the surfaces of modern metropolises like New York and Philadelphia; along the rails of America’s freight trains and in the subway tunnels of its cities; and, though not part of the curriculum, hugely popular on the campuses of art schools like MICA and RISD, graffiti persists as an enduring and ever-evolving form of communication. Playful yet serious, political but subversive, graffiti is the easiest way for anyone willing to take the risk to make their mark in–and on–the world. Graffiti is not taught in school; it is learned on the street. It’s about being bold, but also requires a certain level of restraint. Not every surface needs to be tagged. As with all art, graffiti is as much about what you keep out as what you leave in. No reason to go overboard; leave some room for future writers.