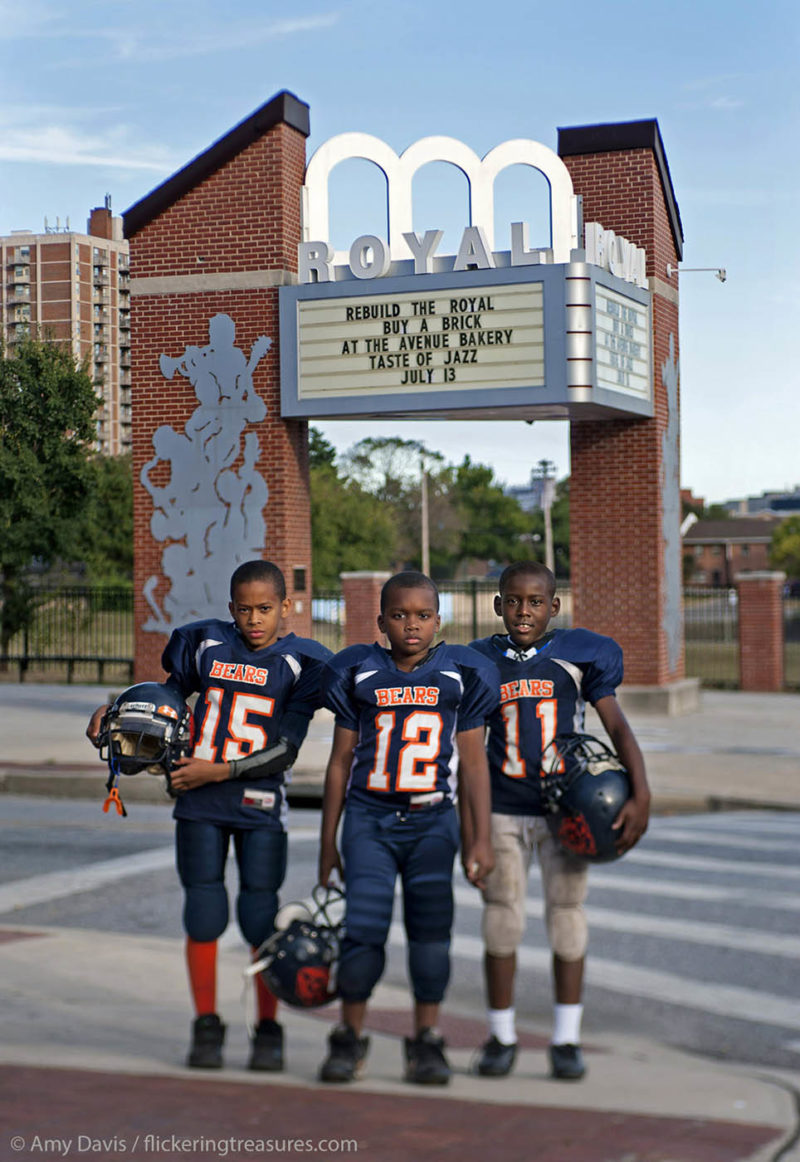

Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist Amy Davis has been working at The Baltimore Sun since 1987. Her book, Flickering Treasures: Rediscovering Baltimore’s Forgotten Movie Theaters, published by Johns Hopkins University Press in 2017, relays the history of Baltimore’s movie theaters over the past century through oral histories, vintage photographs and stunning contemporary photography by Davis. Baltimore filmmakers Barry Levinson and John Waters contribute to the reminiscences shared by theater owners and employees, actors, writers, politicians and everyday Baltimoreans. By contrasting her own color photographs of movie theaters in ruin with historic black-and-white images of those same buildings in their heyday, Davis creates a poignant, pictorial account of the rise and fall of cinemas in Baltimore, once home to over 100 theaters.

More recently, Flickering Treasures has become an exhibition, twice. First at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC, from 2018–2019, for which she was co-curator with Deborah Sorensen; and currently on view at the Maryland Center for History and Culture, Flickering Treasures has evolved into a much larger ongoing project. I recently caught up with Davis, who helped me a few years ago with my own short essay about Baltimore’s crumbling movie theaters, for a brief interview. Here’s what she had to say:

Dereck Stafford Mangus: Did you study photography? If so, where?

Amy Davis: Photography was a required foundation course at Cooper Union’s School of Art in New York City, and I might never have enrolled in a photography class otherwise. I was a design and printmaking major, but before too long, I became captivated by photography. My first instructor looked at my rudimentary b&w prints, and remarked, “This student has a photographic eye!” I didn’t know what the hell that meant, but it sounded promising.

DSM: When did you start working at The Baltimore Sun? What’s it like working as a photojournalist? What’s a typical day like?

AD: I joined The Baltimore Sun as a photojournalist in 1987. In the three-plus decades that I’ve been at The Sun, photo technology has changed radically – as has everything else in our digital age. We were shooting color negative film in the late 1980s. About four years ago we began to transmit photos needed on deadline directly from our camera, via phone to the newsroom using Bluetooth.

Photojournalists tasked with daily news gathering tend to be generalists. I’ve always liked the mix of assignments, from breaking news to features to sports to lifestyle, including food and real estate. The contrasts can be surreal. One winter morning I was photographing at a junkyard, keeping warm in the cab of a truck with the driver, who was homeless. That afternoon I photographed a realtor ensconced in a mansion where the decor was all lavender and purple except for her white poodle. Being a photojournalist is an extraordinary privilege, as people generously let you into their lives and enable you to witness and learn about worlds you would otherwise know little about. These days, it seems that we can’t escape the relentless crime and violence that besets Baltimore, though we try hard to look for the positives.

DSM: What was your favorite shot or series of photos taken while on assignment at The Sun? What was the subject? Why has this shot or series stayed with you?

Davis: In early 2022 I researched, photographed and wrote “Seeing the Unseen,” an essay exploring 19th-century slave trade in Baltimore. This was a project I developed on my own, with the support of my editors who gave me the opportunity to dig into the subject over a few months. The project bore some similarity to my Flickering Treasures book, in that I was documenting sites with specific historic significance, but in this case virtually all physical clues were long gone. For both explorations, I felt the resonance of the past; the layers of history are still beneath our feet and perhaps in our emotional sense of place.

DSM: When did you begin taking photos of cinema houses around Baltimore? What initially drew you to them?

AD: I live near the Senator, a 1939 Art Deco neighborhood movie theater. I was very upset when the Senator, Baltimore’s last single screen theater, faced foreclosure in 2007. Its fate sparked my curiosity about the other once-vibrant movie houses in town. After my photo essay on former theaters appeared in The Sun, I received delightful letters in beautiful old-fashioned script handwriting, often chastising me for leaving out the letter-writer’s favorite childhood theater. I was hooked. These memories helped shape my idea of including oral histories for each of the 72 theaters profiled in Flickering Treasures: Rediscovering Baltimore’s Forgotten Movie Theaters.

DSM: How did Flickering Treasures the book develop? Did you immediately know you wanted to turn your series into a book?

AD: As a Baltimore-based news photographer, I witness the struggles of a neglected and marginalized inner city every day. Despite the challenges, Baltimore is a place I love and am proud to call home. Over the years, I often thought about my body of newspaper work and what I’ve been trying to say photographically about the beauty, spirit and pain of my city. When my neighborhood theater was threatened, I realized that the demise of most of our downtown theater palaces and neighborhood movie houses was a poignant metaphor for a declining city. Until delving into the subject, I didn’t realize how rich the topic of movies and movie-going is, and how its technological, social and cultural evolution mirrors societal change. I also recognized from the outset that our theaters would be an effective vehicle to explore segregation and race, central to the history of so many cities, including Baltimore.

DSM: How was the process of making a book like Flickering Treasures compared to your usual work?

AD: Visually, I wanted my creative process to be markedly different from the way I cover Sun

assignments. The subject of faded or lost movie theaters called for documentary photography that would be open-ended, and less literal than a typical news assignment. I wanted to acknowledge the complex loss that these closed theaters embodied, as former businesses, community anchors and destinations for dreamers. Looking for a way to suggest the layers of history and memories that remain, I decided to try Lensbaby, a lens system that introduces various degrees of blurred effects. I hoped this would invite the viewer/reader to time-travel with me. I also used a tripod, which enabled me to slow down the act of picture-taking and be more contemplative. If there were drug dealers or others who might be suspicious of my presence, the tripod announced a calm (if naive) presence, to counter the suspicion that I was trying to sneak pictures.

In one sense, creating the varied photographs in Flickering Treasures did draw on an under-recognized skill that photojournalists possess: making something out of nothing. For those who think of photojournalism as action-packed, the opposite is often true. We are frequently charged with making compelling images at scenes that seem, at first glance, to be abysmally dull and unphotogenic. Many of my neglected theater buildings can be described this way.

DSM: What did you learn while creating Flickering Treasures, the book?

AD: I was over-optimistic about the length of time it takes to create a book. An estimated three years stretched into nine. One of the reasons pursuing this project appealed to me was because at this time, around 2008, the future of daily newspapers was in jeopardy. Many papers ceased publishing, superseded by websites, and cutbacks were rampant, including at The Sun. It seemed a good time to open a new chapter in my career, literally, by embarking on a book. I continued to work at The Sun full-time, which is one of the reasons the project took almost a decade from germination to publication. I tackled new challenges: fundraising, marketing, social media, archival research, gathering oral histories and using Lensbaby.

DSM: How did the exhibition Flickering Treasures, currently on view at the Maryland Center for History and Culture (MCHC), come about? Did you know all along that you wanted to turn your book into a show?

AD: I had approached the Maryland Center for History and Culture about publishing the book, coupled with an exhibition. MCHC has a remarkable collection of archival photographs, some of which are in the book. The timing wasn’t right, however. After Johns Hopkins University Press offered me a book contract, I decided to seek another exhibition venue for the project. The National Building Museum in Washington, DC, seemed a perfect fit, so I wrote an in-depth proposal that was accepted. My conceptual vision for the exhibition was so detailed that curator Deborah Sorensen graciously invited me to be the co-curator. This 4,000-square-foot exhibition, on view from 2018 to 2019, was extremely rewarding to produce, and well-received. Visitors from around the country, even the world, related enthusiastically to a Baltimore-centric subject. Still, I was very happy the MCHC wanted to help me bring it home to Baltimore the next year.

DSM: Are you happy with the exhibition? How does the show relate to the book? What would you have done differently, if anything?

AD: The concept for this Flickering Treasures exhibition is quite different from the one in DC, so it feels fresh to me. I collaborated with curator Joe Tropea and Baltimore exhibition designer Danielle Nekimken about the image selection, wall texts, and the presentation of ephemera drawn from the museum’s collection. The NBM exhibition featured more than 70 of my framed color photographs, many artifacts, signage, architectural elements, ephemera and a mini-theater. The more compact MCHC is designed to usher the visitor into an environment suggestive of a movie theater, and the gallery used high-quality reproductions of my photographs and archival images for a more seamless look. It opened in the fall of 2020, when Covid-19 was in full swing, but fortunately the museum has extended its run another six months, through March 12, 2023. Both exhibitions and the book present the story of movie-going over the span of more than a century, told chronologically. At its core, my book portrays one American city, Baltimore, through the cultural and social prism of its movie theaters.

DSM: What, if anything, is next for Flickering Treasures? Do you see yourself getting interested in other buildings types in ruin, say churches? There are a lot of old churches around Baltimore.

AD: It was never the “ruins” factor that drew me to the subject. I’m not into ruin porn for its own sake. Funny that you mention churches, though. A good number of shuttered theaters became churches when the movie business shifted to the suburbs, starting in the 1950s and accelerating in the 1970s. Now, fifty-plus years later, we see a steady decline in church membership and the closure of churches. Sounds familiar, huh? As an ardent historic preservationist, it is ironic and sad to see the severe deterioration of numerous theaters that results when churches fold and abandon their buildings.

It is also heartbreaking to consider the future of beautiful but empty church buildings. I have no plans for another book, and definitely not one on churches. I was astonished at the number of theaters that were in operation in Baltimore since the dawn of the movie-going era – several hundred. Just the thought of trying to catalog our churches makes my head ache.

DSM: Having lived and worked through the advent of digital photography–both in still images and moving pictures–what are your thoughts about the digital revolution? I know you probably use digital at The Sun (right?), but do you ever go back to film?

AD: I really enjoyed working with a 4×5 film view camera, and would like to dust off my old wooden Wista 4×5 some day. In a way, Lensbaby is a distant cousin of the view camera, because the lenses can be manipulated in a tilt and shift manner for selective focus. Exploring alternative film processes would be an appealing avenue to explore with my Wista. I have great affection and appreciation for film, but the expense and limitations in comparison to digital make it a tough sell.

DSM: Furthermore, what about digital media in the way we watch films. I believe most major films are shot on film, although that’s shifting too, and maybe some digital effects are used. But having witnessed the radical alterations in the way we experience films via digital technology, online streaming, etc. and how that affects the built environment, vis-à-vis movie houses. Can you speak to that?

AD: For better and worse, digital media is not disappearing, and our beloved film, except for big-budget productions and fine art practitioners, is endangered. We can applaud the democratization that digital media affords, but if there’s one thing I learned chronicling our theaters, it is that loss is a constant part of life. While it’s difficult to predict the fate of movie theaters in a culture that has emphatically embraced online streaming, it doesn’t look good. On a hopeful note, I don’t think many of us expected vinyl records to make a comeback either.

DSM: What is the next project by Amy Davis going to be?

AD: I may do occasional writing, in conjunction with photo essays for The Sun, but nothing long-term is in the works.

* * *

Flickering Treasures: Rediscovering Baltimore’s Forgotten Movie Theaters (the book) is available for purchase at bookstores and online. The current exhibition of Flickering Treasures is on view at the Maryland Center for History and Culture through March 12, 2023.

Maryland Center for History and Culture

610 Park Avenue

Baltimore, MD 21201

(410) 685-3750