The exhibition Matisse in the 1930s at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the only United States venue for this inspiring exhibition, closed on January 29, 2023. If traveling to Nice or Paris, the other exhibition stops, isn’t in your budget there is an excellent catalog. However, the experience won’t be the same. This exhibition is exhilarating and full of insights and surprises. Curatorial collaborators from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, and the Musée Matisse Nice tell the story of how Matisse, then known as a prolific and world-renown artist, worked his way out of an artistic rut and wrestled with the demon most artists face at some point: what’s next?

The exhibition includes more than 100 well-known and obscure drawings, paintings, prints, reliefs, sculptures, documentary photographs, videos, and artifacts, including the actual skirt worn by one of his models, from international institutions and private collections. Engaging signage guided my experience. I was riveted by Matisse’s artistic journey, his personal highs and lows, and to see these events play out in the works on view.

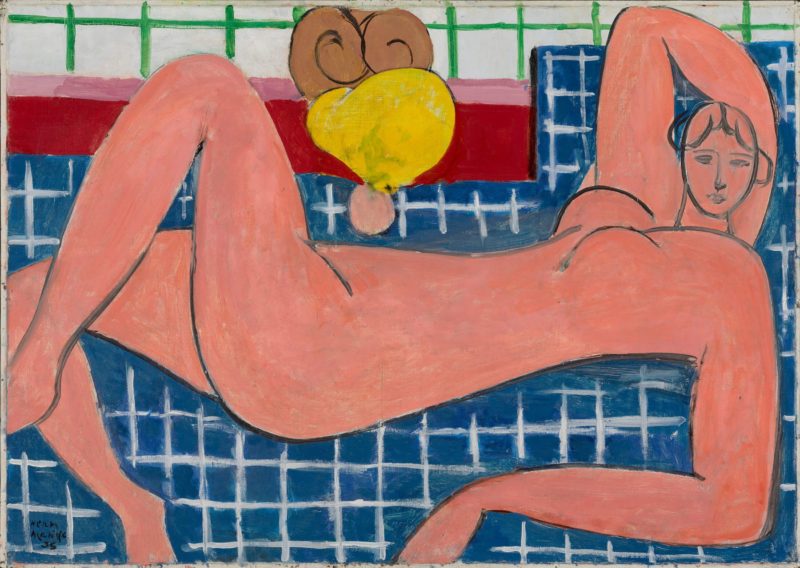

Still lifes and odalisques from the 1920s make up the works in the prelude section. There’s a lotta stuff going on in these easel paintings. Figures—exotically clothed, semi-clothed or naked—are treated as design elements, much the same as his crisscrossing pineapples, hole-y monstera plants, oriental rugs, striped upholstery, and floral wallpapers that talk to each other within the picture plane, all sensuously rendered. The works suggest a world beyond the studio by incorporating Islamic and Oriental designed objects.

We find out that Matisse felt blocked at this point and had stopped painting. Conflict enters the story here. No slouch, Matisse turned to printmaking and produced hundreds of works refining and reducing images and lines to their essential qualities. He also decided to embark on voyages to Tahiti and the United States—the call to adventure for the hero of this story. These trips will have lasting effects on Matisse, which can be seen in the rest of the exhibit.

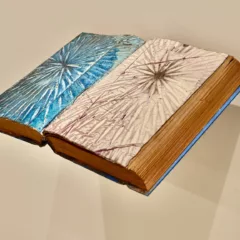

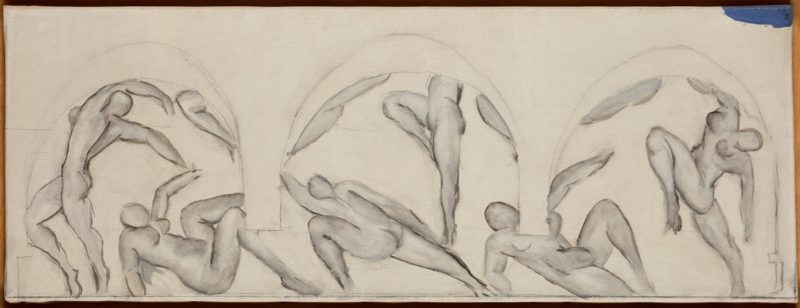

The focus of the second part of the exhibit are two contrasts in scale. First, the 45-foot-long site-specific mural, The Dance, commissioned by Matisse’s wealthy patron, Albert Barnes, for his private collection, originally in Merion, PA, now publicly accessible at the relocated Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, and then illustrations for a book of poems by the Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé.

The mural was exactly the challenge or adventure Matisse needed. It gave him a new way to think about architecture and decoration, and bodies in space. Later in the exhibit we see studies and videos of Matisse’s sets and costumes for a ballet. The mural project occupied him for two years. The exhibition includes a wide range of studies and documentation showing the methodologies Matisse and his assistants developed to complete the work in Nice, such as collaging painted and cut paper, presaging his future cut-outs. We can see how setbacks are handled as opportunities, when he has to rework the mural after having been given incorrect dimensions.

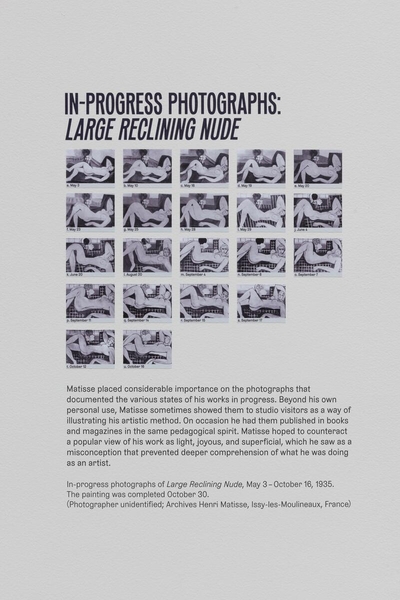

When Matisse returned to the easel his compositions gained more space and his figures feel distilled. They have the simplicity and rhythm that recall earlier line drawings and sculptures. In the next sections of the exhibition, we see how important variation was to Matisse’s creative process, and how painstaking his explorations were. In one of several revealing wall texts, the curators display a series of 21 photographs that captured the changes Matisse made on Large Reclining Nude in 1935.

The exhibition ends with works from Matisse’s Themes and Variations from the early 1940s. These are beautiful and beguiling, simple line drawings depicting themes he had been preoccupied with all his professional life—women, plants, and still lifes—organized in suites by letters of the alphabet. They were made after Matisse narrowly survived an operation for intestinal cancer which left him unable to stand. Faced once more with the question, “What’s next?” Matisse answers with sure-handed and keen-eyed lines expressing the joy of seeing and making, which for him, was living.