The arc of Stuart Netsky’s practice has so far been bookended by the AIDs epidemic and the COVID pandemic. A long-time resident and well known artist in Philadelphia, his current exhibition Walking Backward into the Future, at Gross McCleaf Gallery through March 25th, manifests the charming and incisive continuum of an eclectic, sophisticated artmaker.

Netsky’s first major show in Philadelphia was his 1993 tour de force exhibition Time Flies at the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA). He came out swinging, filling the venue with objects, installations, and photographs, which squarely addressed the AIDS epidemic. In 1992, AIDS was the leading cause of death in the United States for men aged 25-44. Discrimination and ignorance of HIV and towards gay men was rampant and irrational, not unlike the repressive political agendas that are on the rise again and aimed towards the LGBTQTIA+ population. Netsky’s show was an important moment in the crucible of Philadelphia contemporary art history.

Stuart’s response to that crisis established his unique voice. His practice found source material in popular culture, domestic settings, and by critiquing Western art history. His use of materials was innovative and uncommon. Throughout his career various works have been fabricated with medicines normally used to control anxiety, fears, or disease like vitamin C, valium, and AZT. Some of his installations included large hand knitted blankets, or latex-covered and vinyl-upholstered mirrors and chairs; a collection of silver print photographs; or What Should I Wear, a series of self-portraits in which he models women’s clothes he felt comfortable and beautiful in. Fashion has been a constant and important influence in his work. He made paintings with nail polish, lipstick and makeup, or billboard flickers. His work has varied widely in its abundant embrace of materiality, gravitating towards what was unexpected of white male artists. There always was a quality in Netsky’s work that, no matter the seriousness of his subject, was mitigated by a dash of color, camp, and slightly transgressive fun.

Overall, Netsky would say that he has been concerned more specifically with beauty, disease and aging. Covid certainly gave him time to ponder these ideas, while sequestered indoors and unable to partake in public events. So he dove into research that has crystallized his interests in domestic life, popular culture, and Western art history in the new body of work on view at Gross McCleaf. He now has a fascination with François Boucher, the French painter whose work embodies the Rococo style. One of the most celebrated painters and decorative artists of the 18th century, Boucher’s paintings have all the elements Netsky was looking for; color, romance, and sentiment. But for him, here is a caveat; these elements are short lived. In time, they fade and die, as we all do. To accentuate this feeling Netsky juxtaposes cropped images from Boucher paintings with microscopic images of bacteria or flowers. These combinations reinforce the reality for Netsky that we are all vulnerable and will succumb. Covid was a large factor in his decision to include these images in this work. Yet the vibrancy of color and the abstraction of the microscopic bacteria are the mitigating factors that create a tenuous atmosphere for the viewer.

The exhibition features a series of digital prints demonstrating Netsky’s cut and paste photomontage methodology. In Diana After the Hunt (after Boucher), the picture frame is divided into four vertical panes , with the far left image of an orchid next to a section of the Boucher painting of Diana. Juxtaposed to this is a red paint smear from a Gerhard Richter painting and on the far right a psychedelic image of fractals from a Mandelbrot set. These elements bang up against each other in an uncanny but complementary way. In another digital print, Spring (after Boucher), the vertical sections include from left to right a detail of the sculpture Cupid and Psyche by Antonio Canova, Boucher’s Spring painting with a red strip from a Brigette Riley painting covering the heads of the figures; a microscopic image of bacteria, and another part of Boucher’s Spring painting. By melding these disparate elements together Netsky orchestrates his own poetry and lyricism from a lifetime of sensing the vitality in what others may consider disregarded, disparaged, and disowned.

Netsky told me, during Covid “I rewatched the film Sunset Boulevard for the tenth time, and before that I rewatched Suddenly Last Summer, for the tenth time, and tonight I plan to rewatch Valley of the Dolls, for the tenth time. I find in these films the intersection of beauty, camp and disease, whether physical or psychological. Cinema inspires my art practice as there is a cinematic editing that occurs in the new work, and this editing is a device I use to splice the imagery that film, art history and other sources supply.”

It may explain why, in his large mixed media work Diana and Liz After the Hunt, there is an image of Elizabeth Taylor from the film Suddenly Last Summer. This piece provides insights into how disparate ideas, film stills, objects, and images from art history come together into a jumble Netsky then edits and splices together. In the rectangular painting, a photograph of young Elizabeth Taylor looms in the foreground. Next to Liz, Meret Oppenheim’s fur covered surrealist tea cup is slyly included into the tableau. Diana and her consort lounge behind, their gowns fluttering in the breeze. A pair of deer antlers are affixed to the head of Diana and stick out and above the frame. The completed piece feels like a post pop reverie, a mirage, a gathering of vanished Goddesses along with their sensibilities of gracefulness. While Netsky wrestles with loss and inevitable decay as leitmotifs in his work, he still finds space for his innate humor and fragile optimism to find a way in. This is an improbable work, unexpected, and a strong one in the show at the gallery.

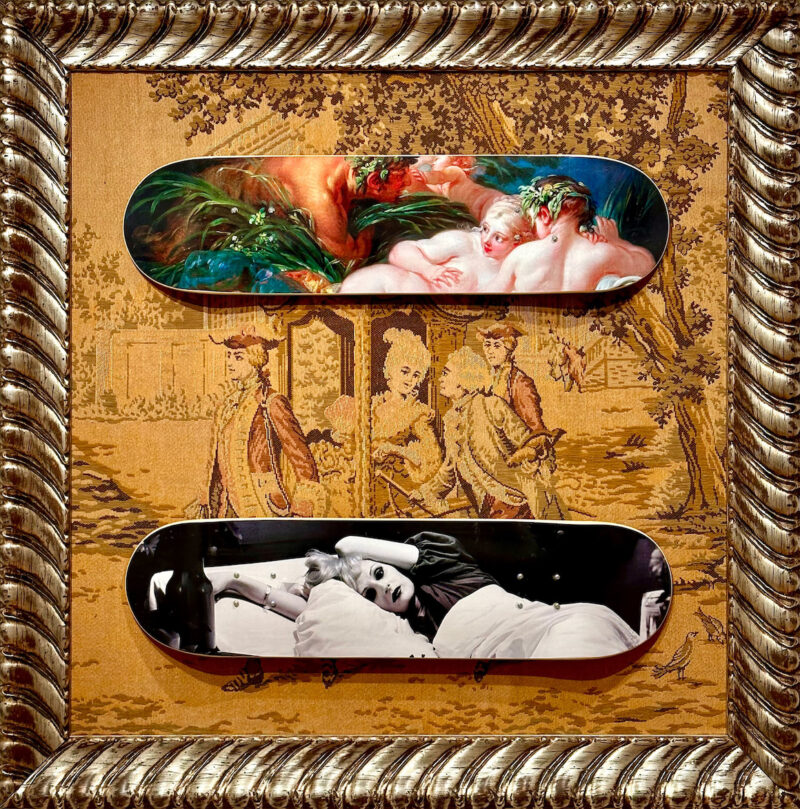

Walking Backward into the Future has a number of distinct mixed media works that feature skate decks fixed onto large canvases. At first glance, one may wonder why now, since skate decks have been used by numerous other artists. Artists have liberally imprinted their work on skate decks, appropriating street culture, and then sold them in museum gift shops as high priced limited edition swag. This is the point of Netsky’s skate deck work. He has no particular interest in skate decks per se. It is more about his fascination with retail marketing and the “exit through the gift shop” phenomena that has become the end game of the corporate museum experience. Netsky finds the assortment of gifts staggering. While the crass commercialism of it angered him at first, feeling it cheapened the aesthetic experience one might have had, he adopted this high art market capitalist tactic for his own purposes. He began to create installations in conjunction with the theme of his shows, providing a wide assortment of self-produced products like ashtrays, pillows, scarves and floor mats.

Around 2014, he started to see editions of skate decks. Artists like Cindy Sherman, Paul McCarthy, Robert Longo, Marilyn Minter, Louise Bourgeois, and Damien Hirst capitalized on the skate deck fad. Netsky decided to make some of his own custom decks, though for different reasons. Emblematic of this series is Candy Go Lightly. Netsky found an untitled rococo style tapestry at a flea market, which became the background. He attached two skate decks embedded into the tapestry. The upper deck is emblazoned with an image from Boucher’s Pan and Syrinx, while the bottom has a photo by Peter Hujar of Candy Darling on her Deathbed. All of Netsky’s themes, whether commercial consumption, loss, fashion, romanticism, decay, glamor, or art history, are bundled together in this work. He works in distinct series, and as he has written, “creating a crazy quilt of pictorial eclecticism that obscures our ability to make sense of the image, acting as a metaphor for the confusion and shifting dichotomies in social interactions.”

Some of this is evident as Netsky pokes some much needed fun at the male gaze in Have Your Cake and Eat It Too (After Fragonard). The central figure of the woman on the swing is being ogled by two men, one of whom seems to be looking up her skirt. A large wedding cake protrudes from the surface of the canvas. It is placed over her crotch. If a line could be traced from the gentleman’s pointing finger up her skirt, it goes straight to her vagina. Fragonard and Boucher, perhaps purveyors of the 1800’s version of soft porn, are sent up by Netsky in this hilarious and honest piece.

Netsky, an important artist in Philadelphia and to the national cultural canon, views himself as a singular artist, who embraces nostalgia and romanticism for their tender and universal sensibilities to counter the inundation of imagery and information that bombards us, to deflect the absurdity he experiences in contemporary culture.

Treat yourself to Netsky’s work, up through March 25, at Gross McCleaf Gallery.

Clayton Campbell is an artist and writer living and working in Philadelphia.

For previous Artblog coverage of Stuart Netsky, we recommend these posts:

https://www.theartblog.org/2006/02/weekly-update-stuart-netsky/

https://www.theartblog.org/2006/01/imitation-of-life-stuart-netsky-beneath-the-skin/

https://www.theartblog.org/2015/01/sparkling-sirens-stuart-netsky-at-bridgette-mayer-gallery/