In the last hour of Rosine 2.0, a figure in the center of a gray quilt semi-circle asked “What does harm reduction look like?” and then closed the daylong program, an event held at the Icebox Project Space on March 18th. The community-focused event centered around sharing the Rosine 2.0 collective’s ongoing archival projects, showcasing photographers, hosting Philadelphia mutual aid organizations, and practice workshops from the event coordinators and local organizers. The large event space, inside the Crane Arts building, was sectioned off into separate smaller stations for arts practitioners, organizations, and micro-exhibits. The event also featured free original publications from some of the highlighted artists and facilitators, available only that night. Through the combination of many socially-informed installations, stimulating group discourses, and accessible supplies, Rosine 2.0 as a collective project proposes answers to the first facilitator, Raani Begum’s question at the conclusion of the event, through its artistic stations and exhibits.

Organizations like Philadelphia Red Umbrella Alliance, West Philly Bunny Hop, Homies Helping Homies, and The Puzzlement Laboratory lined the perimeter of the event space, sharing free resources and advocacy materials from topics such as bereavement support to sex worker safety volunteering. The tabling organizations did not limit their full embrace of harm reductionist language, while ignoring respectability politics. In their introduction, the collective made clear they include sex workers, drug users, and former drug users, who passed out free sexual health safety supplies for full-service sex workers, bandages, needles, and safe snorting supplies. On the other hand, a mutual aid org like Homies Helping Homies set up a fully-functioning photo studio for attendees to get free professional portraits done.

Many of the installations and exhibits at this event centered on photography or archival work and explored similar, interrelated themes. One photo exhibit on the wall, titled “What Heals You” by sex educator Yema Rosado and curator Zissel Aronow, involved portraits of many community workers on 35mm film that lead to QR codes with more information on answering these three questions: “If you frame your work as an offering, where do you give from,” “what heals you,” and “what has Philadelphia taught you?” The portraits involved hazy, peachy hues over a smile or a straight gaze in an environment that best represented the energies of people from diverse backgrounds: growers, witches, weavers, researchers, teachers, archivists, educators, cultural workers, land stewards, and performers. In a QR code link to an audio file of each of their interviews under their peering portraits, each practitioner opened up on the most intimate relationships with their work.

In another corner, four tables were set with emerald green tablecloths and plastic prop foods scaled and layered in an arrangement of a large, multi-family dinner. On closer inspection, the tables were covered in craft paper printed with line drawings of photo frames. Generational Feasting, the collective responsible for the installation and organized by Sabriaya Shipley and Rosie Morales, are an ethnographic photography, videography, and interview project creating dialogue between Black youth and older generations. The only part of the exhibit that did not require the attendees’ involvement was one table set as an altar with pictures of Black and immigrant children, who died at the hands of the police or colonial state, surrounded by candles.

At the first table that other event attendees and I were invited to by the collective’s organizing youth, guests were encouraged to admire the faux-food feast, sit, and enjoy Youtube video links of some of the collected interviews via QR codes that documented how youth see their community members, what feasting together looks like from quotes like “eating together brings comfort” or that “our communities need to sit back and laugh together more.” Afterward, guests were invited to get up and write what community means to them with colorful markers on the frames printed on the “tablecloth.” The sheet was scribbled with sentiments like “decriminalizing sex work,” “decriminalizing existence,” and support for the anti-Chinatown stadium protests. <https://www.inquirer.com/news/chinatown-reiterates-opposition-sixers-arena-20221130.html> This multi-media installation’s interactive appeal honed the concept of community-building it acknowledge by inviting guests to share and add to the space, and providing a space to rest to examine the fresh archival materials that the organizers collected.

Through this event, it was evident that the artists and researchers in Rosine 2.0 through their services, installations, and photography utilized the archival process. It was fresh and invigorating to see appreciation for archivism as an artistic method of research, cultural production, cultural protection, and creative presentation. Rosine 2.0 preserved the work of these radical cultural workers and activists and through many different types of works exhibited them through striking photo projects and thought-provoking conversations.

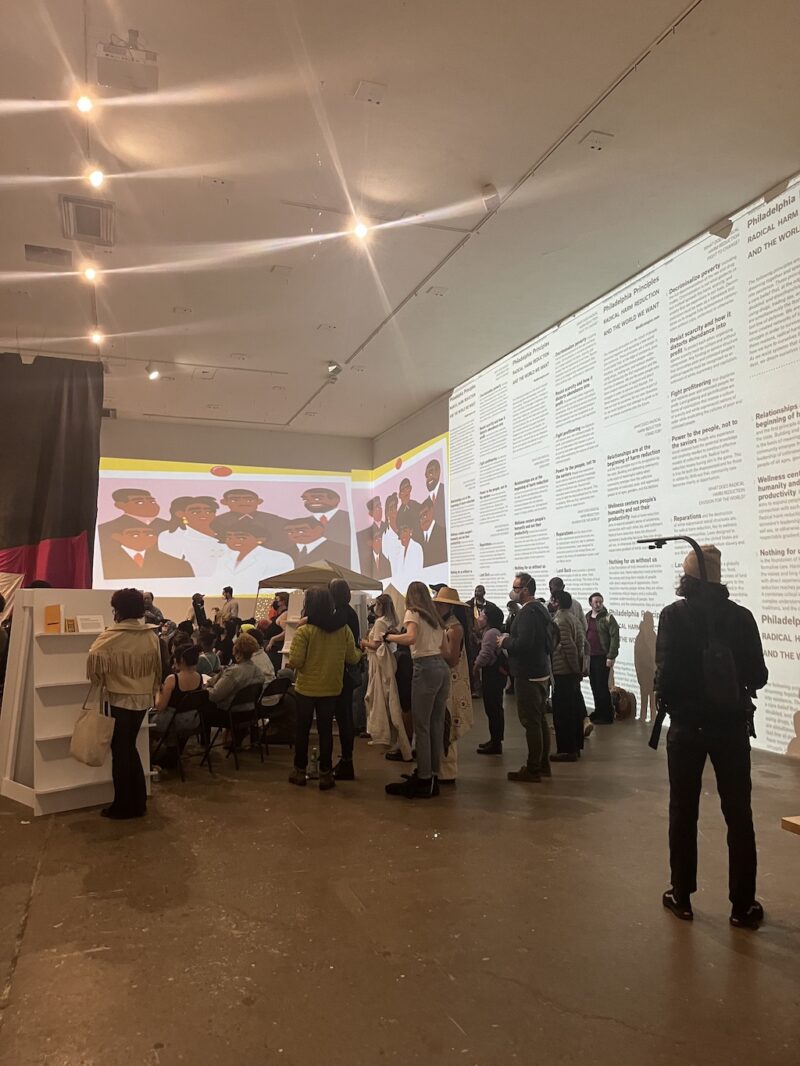

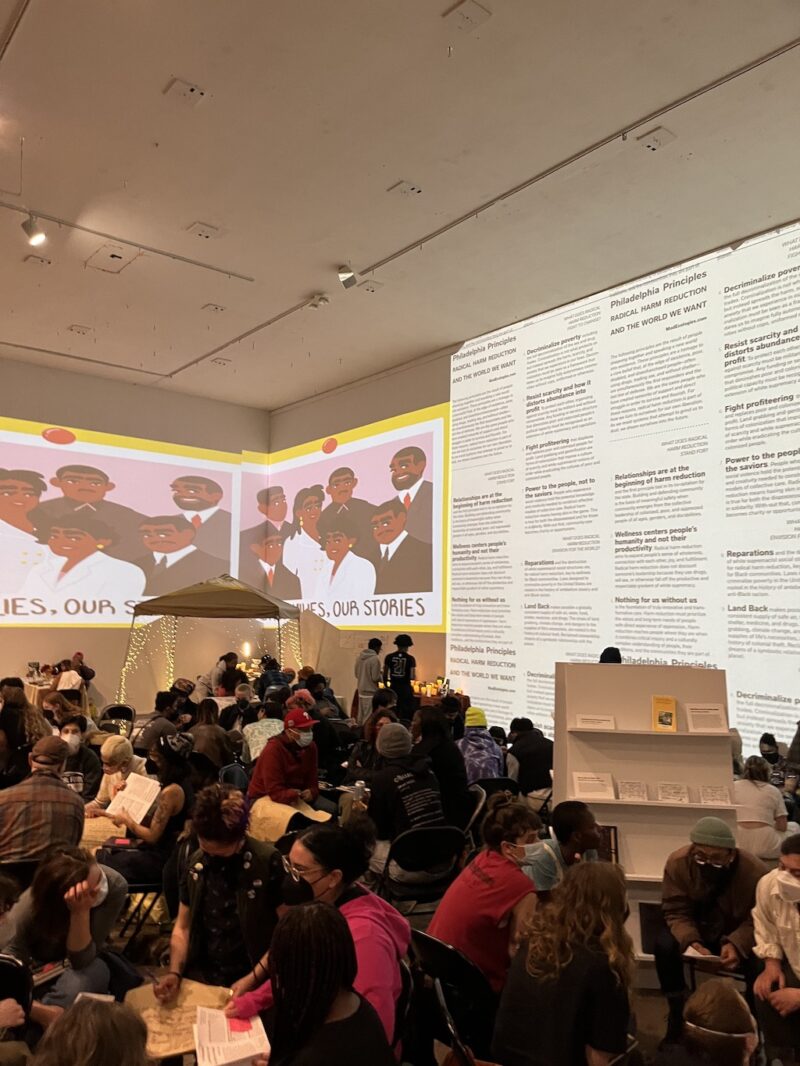

After Raani Begum, a full-service sex worker, activist, and writer, posed that question for the closing workshop, the audience broke into their own pods of eight to ten people as instructed and discussed what harm reduction meant to them. Begum’s workshop was the last one of the day, following a community care and herbalism workshop and a land revolution workshop. Begum cued the attendees with a full wall projection featuring tips on what harm reduction might look like, from the basic idea that “wellness centers people’s humanity and not their productivity” to providing a basis for understanding what “reparations” means for disenfranchised native Philadelphians.

While Begum’s question could not be answered entirely in one night, Rosine 2.0 offered possible solutions to harm caused by capitalism and structural racism. Based on the archival materials and stations, the answer might look like an understanding of where a person’s place is as a native, gentrifier, transplant, class collaborator, or class traitor; highlighting the importance of community-building and how important community-based practices are in creating radical art. In the midst of a semicircle, quartered from the rest of the room with floor-to-ceiling wool curtains pinned together with vibrant patterned rugs and shawls, I watched the crowd break into the final chatter of the day that, I suspect, like me, stuck with them well after they left the building.