Back in March, Artblog’s Niko Walczuk reported on the exciting news that a solo exhibition of the work of Odili Donald Odita, a painter and professor at Tyler, had just opened at the Stevenson Gallery in Amsterdam. Although I was not able to see Odita’s show before it closed, I was able to scout out Philadelphia’s presence in other art contexts.

At the Alfred Ehrhardt Foundation in Berlin, I made it a point to see Philadelphia photographer Thomas Brummett’s show, “Seeking the Infinite.” Some of the works in the exhibition are not “photographs” per se, in that they are not produced with a camera. For his Light Projections series, he uses a lens to project “circles of diffusion” — which in medical terms has been described as “one or more circles on the projection plane of an image not in focus of the lens of the eye” — onto photo paper. He then proceeds to employ a variety of types of manipulation (solarization, etc.) in the darkroom. The effect is ethereal.

For Infinities, he starts with images from the Hubble space telescope and then overlays these views with natural details from our home planet, such as flowers, snowflakes or molds. The works call for contemplative meditation, as the macro and the micro meld together. We humans are but tiny pieces of dust in the cosmos, he seems to be saying. But each of us contains multitudes.

Although the gallery space itself is somewhat confined, Brummett’s photos are nonetheless expansive. The show continues through July 9, 2023.

Another Philadelphia photographer, Blaise Tobia (full disclosure, Tobia is my husband), has photographs in an exhibition that opened on April 29 at the Kunsthaus Dahlem in Berlin. This historical show focuses on Paul Jaray (1889-1974), a revolutionary thinker who, in the 1930s, designed the first car to hit 300 kilometers per hour. However, his name has essentially been erased from history. As a Jew in Nazi Germany, the large car manufacturers forced him to remain in the shadows, and his aerodynamic breakthroughs were attributed to other designers. Jaray’s visionary ideas, however, found their way into Futurism and Modernism, and they continue to inspire contemporary artists.

This exhibition was first curated by Wolfgang Scheppe for the Arsenale Institute in Venice last spring, and called “The Architecture of Speed.” The Berlin version of the show is titled “The Rationality of the Streamline” and has been considerably expanded. It brings together documentation and original artworks from an extraordinary breadth of sources, ranging from Jaray himself to artists like Kurt Schwitters, Allan Kaprow and General Idea.

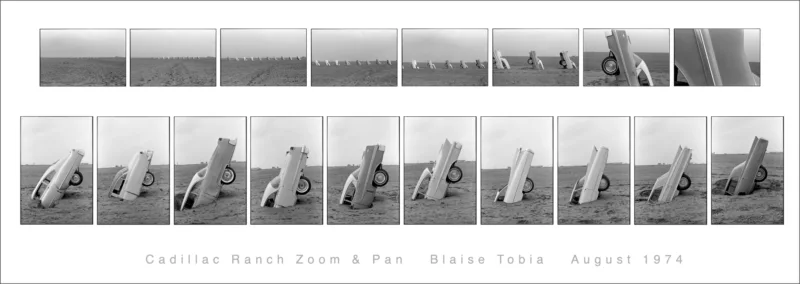

Tobia’s photographs comprise a unique documentation of the Ant Farm’s Cadillac Ranch, a series of 10 Cadillacs positioned nose-down in the ground alongside Interstate 40 in Amarillo, Texas. Now graffitied and strewn with trash, Tobia photographed them in near-pristine condition, shortly after their installation in 1974. Titled Zoom and Pan, the photographs form a sort of filmic panorama, in the sense that they emphasize the movement of both the camera and the cars themselves. Tobia calls his approach “structured documentary.”

Moving on to Amsterdam, the context changed from seeing the work of Philadelphia artists to unexpected close-to-home connections. It proved impossible to secure either a ticket or press admission to the Vemeer exhibition at Rijksmuseum. The closest I got to the Flemish Master was the “De Parel van Delft” saison bier I drank in the lobby café.

While sitting there scrolling through my tablet, I discovered that the Philadelphia Museum of Art might very well have its own Vermeer, Lady with a Guitar. According to Artnet News, the PMA has had the painting in its collection since 1933 but has never exhibited it. Apparently, experts had thought it was a late 17th-century copy because there is a nearly identical painting with the same title in London. However, Arie Wallert, who has worked as a curator and museum scientist at both the Getty Conservation Institute and the Rijksmuseum, presented new findings in March at a symposium held in connection with the Vermeer show. His conclusion, based on a detailed analysis of the pigments, is that the PMA’s painting is not a copy. The pigments in Lady With a Guitar — especially a type of ultramarine and lead-tin yellow — were used in “combinations that nobody else used at the time,” Wallert said. PMA’s director, Sasha Suda, laments that the painting is in a “highly compromised state” due to damage suffered and inadequate conservation prior to its arrival at the museum. Given its poor condition, Lady with a Guitar, will likely remain in storage for some time. [Ed. Note: Lady with a Guitar is on view for a short beginning June 10 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, before being taken down later in the year for research and conservation.]

What the PMA does have on display in the Toll Gallery on the second floor is Claude Monet’s The Zuiderkerk, Amsterdam (Looking up the Groenburgwal), painted in 1874. Interestingly, the museum’s website says that it was “probably” made in the Netherlands. Well, I can tell you that it was “definitely” made in the Netherlands, or at least it is a studio work made from sketches made in the Netherlands. The view is towards the Staalmeestersbrug Bridge as seen from Amstel.

Except for boats in the foreground and a few new buildings, the photo overlaps perfectly with Monet’s canvas!