Author’s Preface

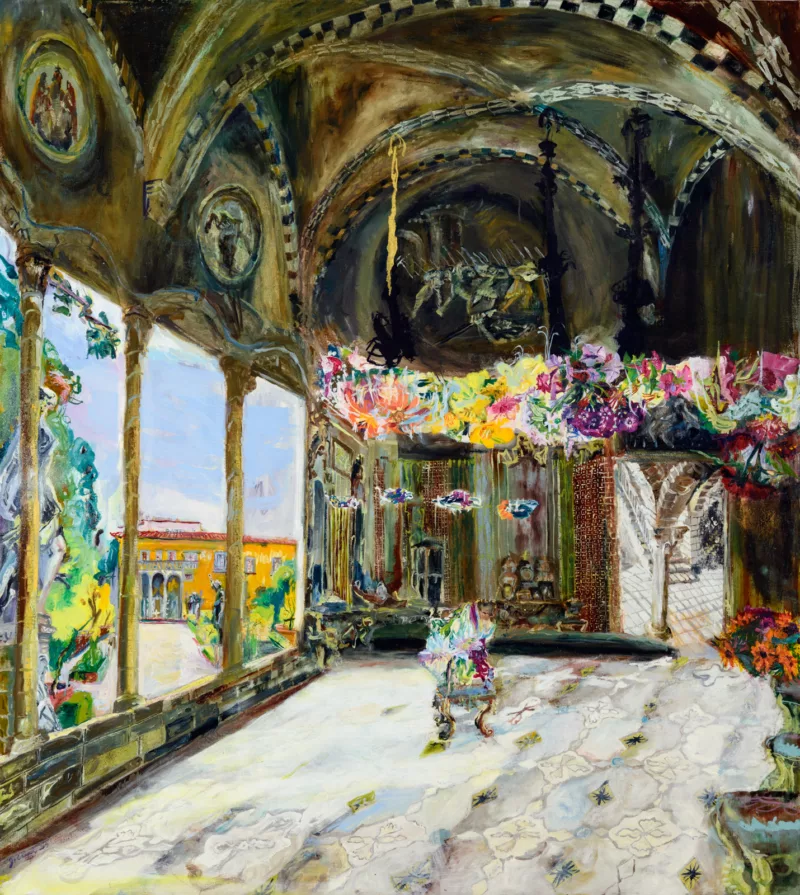

Eureka: New Works by Jane Irish, opening at Locks Gallery September 1, 2023, continues the artist’s research into the possibilities of images suspended between the echoes of atrocity and the immediate beauty of painted worlds. In her Northern Liberties studio, we have a wide-ranging conversation about material, the testimony of Vietnam War Veterans Against the War, Edgar Allen Poe, and artists’ roles for the future. We sit, surrounded by pairings of paintings both cosmological and interior: swirling skies give way to architectural layering of pink, orange, yellow—figures emerge from dense foliage that conceal violent acts—a lime chair sits beneath a panel painting of a triumphal arch—there are blues, chromatic pink-whites, dirt-green throughout. The show’s title references Edgar Allan Poe’s 1848 ‘prose-poem’ of the same name, a religious-philosophical treatise that Irish has studied and culled from in her visions of the future.

In her studio, four blue, tall-necked vessels with yellow insignia are on display, as if they are in a stop-motion of pouring. They have the matte quality and color language of Wedgwood, with the yellow in counter-relief. [Note: The interview has been transcribed and abridged for publication.]

Kate Brock: So in the most skeletal way, walk us through what is in the show. My understanding is that in addition to your new paintings, there might also be ceramics?

Jane Irish: I’m thinking I would like to show my most recent ceramics. They are simple but very time consuming, because I learned this whole process again. I wanted to present it [the works] as one piece with four objects. It’s called Water Carrier the bottom sprigs have a flow chart of deserters and accused draft offenders, those who were prosecuted or got amnesty. It [the sprig, a piece of press-molded clay] reveals itself as you pour.

The paintings are really recent, intentionally smaller and they are oil. I had been working with egg tempera in this WPA (Works Progress Administration) method that uses canvas rather than board. It was meant for mural painting. I always thought oil has a caveat, that it comes with a lot of pats on the back or ‘wowness,’ which I’ve avoided. At my installation at Lemon Hill, the ceilings were in oil; I also started using distemper, which is a theater paint that they used in Beaux Arts, like Chagall and Picasso. If you think of an old theater backdrop, it has this kind of dim quality to it that is very painterly, too. It lets you be expressionistic because it cools within a certain limit of time. I love the quality of age that it has, it’s kind of a poor man’s tapestry.

Sometimes the paintings are used as props in other interior paintings. It’s a way of emphasizing more of a truthful telling. There’s a deliberate painterliness to what I am doing, people can see how it’s made.

Kate: Something I enjoy in your work is the spatial push and pull on every level, which a theater backdrop does explicitly. It can be hard to pull off in a smaller painting, because the viewer is going to want to orient themselves in relation to the shifting perspectives, to make it make sense. But these paintings override that desire, so you have to accept or believe in these melding zones of decoration in one spot and deep recessional space in others.

Jane: I guess it’s making people feel, when they’re looking at the work, that they are unsure of their stance in relation to it. I think about that: the feeling of unbalance in relation to history, to suffering. I’ve always tried to present peace history. Many years ago I did a commemorative show about the Vietnam Veterans against the War, a group that was based in Philly, New York, and the rest of the country. They were against the war, but they had already served. I thought that was a great metaphor for being an artist: we’re against, but we still serve, and we’re part of it at the same time. I got to the point where I was meeting all these anti-war organizers who were liking my work. They started giving me a lot of photographs, and one man gave me his papers which recorded a guerilla theater event that the Vietnam vets did in Detroit, where they made their own testimonies of atrocities.

Each of the paintings in Eureka have a correspondent text extracted from these testimonies. Irish shares one connected to ‘Supplicant’ in which the figure of a man cries out for water, pulled from a Renaissance image which Irish has rendered in umber and siena strokes.

Jane, reading from the 1971 testimony:

Bob Clark: I served with Gulf Company Two Nine.

Moderator: You mentioned the killing of wounded prisoners. Would you talk about that also?

Clark: Right on. On June 13 on Operation Cannon Falls, we were on Fire Support Based Wisemans, Gult Company and H and S company. A man was screaming for water and they just poured it on the ground.

Jane: Each time some Renaissance imagery appears, it comes from me trying to read this testimony and think about the question: This imagery that is constantly delighted in, in museums and everything, when people view it do they think of the act of starving someone, of all the violence that permeates it? I’m trying to understand as an artist, where does the violence start with me that creates this horror in society. And so I look back at painting.

Kate: I love what you said about artists resisting and participating in these power structures but continuing to serve. Because we have art history, a trove of all this gorgeous, horrific stuff. Like how are we supposed to metabolize it for this moment? It can be so seductive, to miss the violence completely. How do you relate to beauty in all of this?

Jane: Of course, I love painting. Because of the Vietnam war history, I’m also very much trying to understand other canons. I look at a lot of Vietnamese ceramics and try to utilize that as part of my brushstroke. I’m thinking of my mentor-poet who says, “You get them in any way you can.” And so if it’s beautiful, that’s one way.

I want to draw someone in and give them questions, as well as to present the truth in some way, as though these images were the future. Which gives some answers as well. Usually what we think of as futurism is beauty imagery, kind of an obfuscation of the atrocities. Like instead of someone getting beaten up, two people exchange the letter. What if the future reveals itself also in a negative sense, like Christmas of the past and future. I’m telling the truth about the atrocities. Sometimes I try to present a peaceful existence before colonialism.

Poe talks about, in his prose-poem “Eureka,” how do you develop belief in something that is possible, but that doesn’t exist now. It’s just as hard to understand limited space as it is to understand unlimited space. So, to pair those two—the cosmos and the interior—and to bust them open. He’s also very cool about artists’ role in society: we intuit forward thinking, and society finds proof scientifically and mathematically later.

He read so much, all the scientific journals, and absorbed everything and then pulled this poem out. That’s the way we are today. Artists totally immerse themselves in histories, they can see, they’re reading so much.

Kate: Yes. I was recently describing my worm composting bin to another artist, and how the worms can eat so much more than their body weight and they produce these amazingly rich castings. That’s what we’re all trying to do, we weren’t invited to the feast, the banquet has already happened. And we’re just tasked with getting the soil ready for someone else after. I’m really enjoying the way you bring materials, images, and histories together that touch this relationship between violence and the image or enaction of it.

It feels like a serious and hard thing to do with violent imagery, to break it open into a new space. I want to ask you about your relation to war photography. There’s such a meeting point between belief and event in war photos. There’s not an ambiguity about what the atrocity is, but there is, for me, a question about why I am looking at it, or where am I in relation to it. Photography can be sneaky in how well it hides the composition—the strength of what you’re looking at is so compelling—but in painting there’s no question about play, deliberation, composition. The viewer knows they’re being led.

Jane: I think about that all the time in photography. As a figurative artist you either have a great intuitive ability to invent figures, which I don’t, or you’re looking at photographs. Lately, I’ve been working from bas-reliefs or sculpture—so I can get another view. It gets me more intimate with the imagery.

I still feel that when we are at war, our culture melds forever. I try to be a part of Vietnamese communities, both going there and meeting with artists and talking language here in Philly. There’s an anti-war group I find inspiring—they saw my work and asked if I would attend some of their meetings. My work is educational in a way, and I hope to send it into public as often as I can to have conversations about how these images come together. I still feel like an artist more than a community worker.

In my older age, I’m allowing myself to rupture the reality, and hopefully it speaks. As visual artists, we can do it.

“Eureka: New Paintings by Jane Irish,” Locks Gallery, Sept. 1 through Oct. 13, 2023.