“I think it’s very funny when people take me seriously –

I just do my thing and I don’t really care if people like it or not.” – Anne Minich, 2023

[Ed. Note: Anne Minich is quoted from her artist talk, which took place at Commonweal Gallery on 9/21/23.]

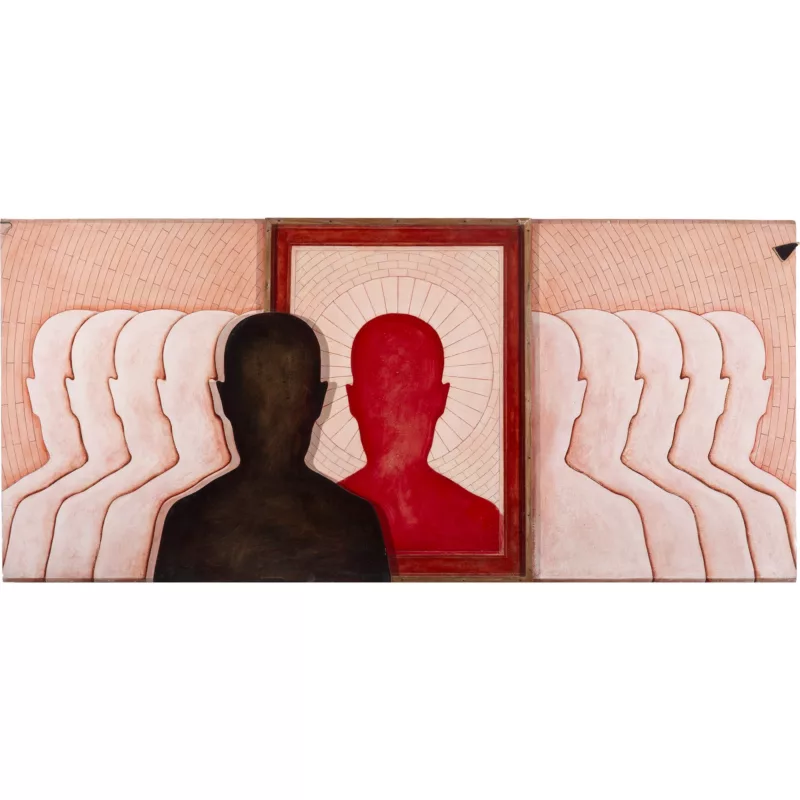

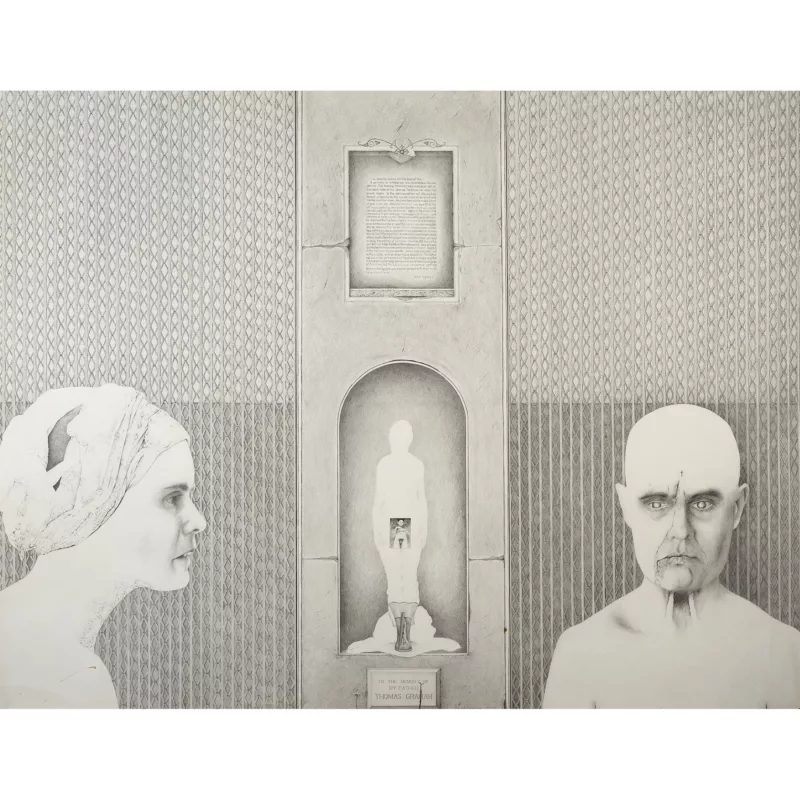

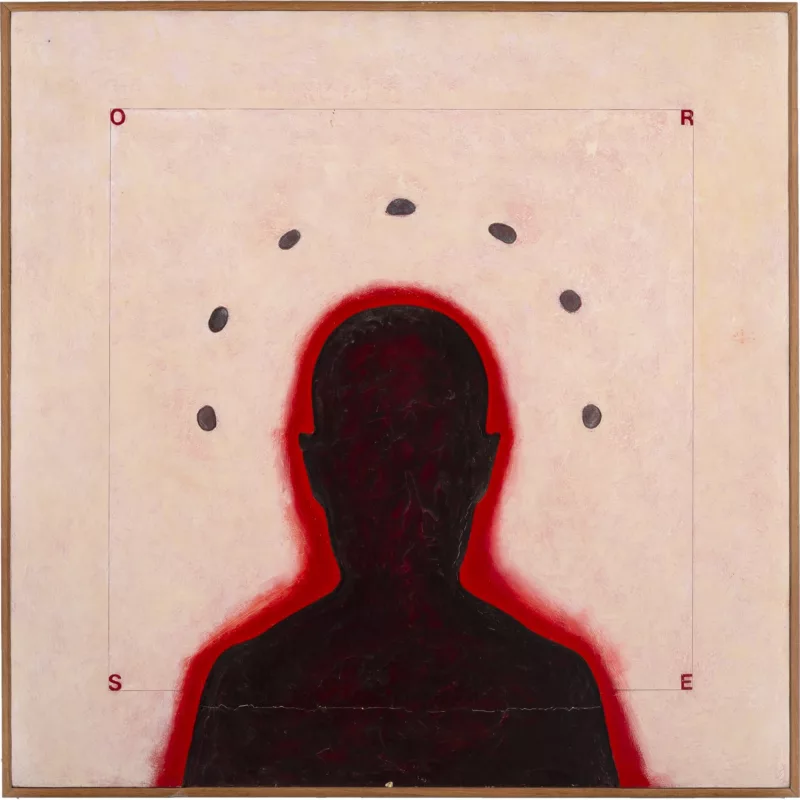

If you make the wise choice to visit the installation of Containing Multitudes: Anne Minich’s Head Series, 1974-2023 at Commonweal Gallery, upon entry you will be surrounded by an experience that is utterly singular. The gallery is lined with paintings that are carved into and graphite drawings of silhouetted heads. Almost the antithesis of a portrait gallery as there are no faces to recognize (excluding a profile view of Minich’s son in “Observant Son”). The outlines are at once specific and generalized – they could be anyone – an effort by Minich to, as she says, “Take all meaning out of it.”

Each of the compositions is symmetrical, from 1 head to 12, mimicking the symmetry of our bodies but also religious icon figures. Some heads are emblazoned in bold contrasting outlines – others filtered and shaded through veils of trompe l’oeil pieces of paper. The shadowed bust provides a blockade to recognition but even then more barriers are called upon. Rich patterns obediently march across a confessional screen, sometimes all but obscuring the figure (in “Daughter,” “Blood Bride,” and “A.E.”), sometimes falling behind the figure to form a stage. The patterns are created through difficult and intricate processes, delicate shading, painstaking carving of lines, or creating spaces to embed objects. These details emerge slowly, with intensity, as a kind of rote obsession given meaning through repetition. These textures and patterns emerge from Minich’s Anglican upbringing.

The reference to a halo or a spotlight appears throughout the works (in “An American Icon (Our Lady of Francisville Barbara Jean)”. The idea is of saints and performers being called upon for many different services. Minich recognizes that she is a performer in the work, “When you’re doing a self-portrait you’re very much on stage.” Her figures at times are positioned on a shelf-like set. Minich tries on different roles, the most prevalent of which, she was cast as the Virgin Mary, as a child in a passion play.

While creating her head pieces, Minich is the audience to her own work, making things she believes “look well.” In the mother of all the head pieces (“Aqua Bride”), she has depicted herself twice, the right facing frontally and the left looking in profile to the right. “I used to call this piece ‘Me Talking to Stupid’”. The shading builds in gauzy kisses so fine and so detailed that it seems to grow from the will of the paper itself. It is one of the few works where the people have faces. It provides somewhat of a key for our understanding. She visually depicts herself as the observer of herself. In the rest of the works, Minich repositions the role of the observer outside of the picture plane, she steps into it while she makes the work, and then allows the viewer to take her place when it is complete. While looking around the gallery at 49 years of work, Minich said that she was “Seeing them in many ways not as mine anymore.” A fair amount of the work is loaned from museums, collectors, friends, and family. She noticed how she was able to see the works as objects. Most everything that Minich does to her paintings is to state the object-hood of them.

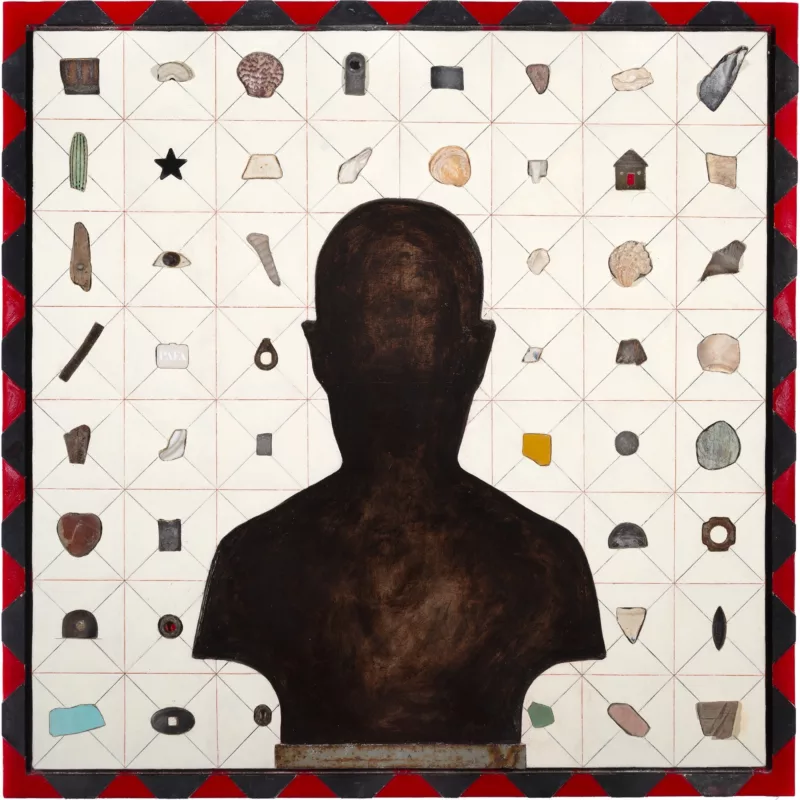

She conscripts the material to her will, plunking found objects into the surface, embedded like candles on a cake. The stabbing gesture obscures the careful deftness with which each notch is cut out in the precise outline of each shell, rock, nail, ceramic shard, and gear. The words and objects receive a similar treatment, scratched and impressed into the wood. From Vilem Flusser’s book “Gestures;” according to tradition, this is the origin of writing. It was about making holes, pressing through a surface, and that is still the case. Writing still means making an in-scription. We are concerned not with a constructive but with a penetrating, pressing gesture.” (Flusser, p. 19) The words and objects are reached for in a similar way. Both are used as symbols with inherited meaning, their wills exercised onto the writer and the reader. “I feel compelled to put words together,” Minich says it is her poetry. The objects and words are plucked intuitively from a lexicon of religious iconography and items found on the sidewalks of Philadelphia. In “Object Poet,” the objects form a gridded language. They create an associative poetry, linking to something larger than themselves. “To alter one single aspect of this accidental structure… would mean to change our way of being in the world.” (Flusser, p. 20) Minich said that when something’s important to you it gets embedded. When asked why she said, “Never thought about it, something I do like crossing the street.”

There is nothing in Minich’s work that she did not put there intentionally, nothing is by accident and yet many things are a product of chance, coincidence, or mistake. From misheard phone calls, to scattered drawings, to roadside bottle caps, she is always collecting material for her work. “There are 24 hours in the day at an artist’s disposal.” She says there is no excuse not to use every one.

In all the works, Minich brings in the visceral, the sensory, and the deeply physical. Whether that be simply in the tactile nature of the found items embedded, the scrawled messages (Bitch), or the wound-like borders of some of the heads (Sore Spirit). The borders of the heads blush with value, like the edges of peeled skin, a fresh edge. Some of the heads appear as though they have been picked off like a scab. Others curling forwards, or tacked down with comic faces or skull-piercing shards (“Annunciation in NYC”).

Minich had misheard a dear friend, Juan Gonzalez, on the phone when he was trying to tell her about the poem “The Rebel” by the poet Baudelaire, and she thought he said “Rainbow in Bottled Air” (Link to poem). The resulting work from that misunderstanding, “Our Lady of Rainbow in Bottled Aire (SAD)” nods forward in space, down towards the viewer. It brings to mind Proust’s description of his mother at night silhouetted without features, bending down for a kiss. We don’t know what she’s thinking or feeling, as we can only see her outline, “And to see her vexed destroyed all the calm she had brought me a moment before, when she had bent her loving face down over my bed and held it out to me like a host for a communion of peace from which my lips would draw her real presence and the power to fall asleep.” (Proust, Marcel. Swann’s Way. Translated by Lydia Davis, New York, N.Y., Penguin Books, 2004. p.13.)

A question may emerge – are these outlines all of the artist?

Is this show a collected portrait of many multitudes of one person as the name suggests? I would argue yes and no. Figures of disassociated divinity, conjured in so many places at once, replicated repeatedly, with no center. Is the silhouette in the door a mother, an artist, a god? You cannot look directly at her, is she there at all?

The only appropriate way to answer a question in which all answers are truthful, is with another question — Are the figures in front of you? Or are they holes? We see many labels, and many roles, some would appear conflicting. “But even with respect to the most insignificant things in life, none of us constitutes a material whole, identical for everyone, which a person has only to go look up as though we were a book of specifications of a last testament; our social personality is a creation of the minds of others. Even the very simple act that we call “seeing a person we know” is in part an intellectual one. We fill the physical appearance of the individual we see with all the notions we have about him, and of the total picture that we form for ourselves, these notions certainly occupy the greater part.” (Proust, p.19)

Women have always identified strongly with Minich’s work. She emphasizes, however, that the figure in the head pieces is not a man or a woman. Minich is not speaking to women, but rather “consciously trying to speak to anyone who’s listening.”

To me, the work surrounds the being of nothingness. But there is no contradiction present. Minich’s figures are both falling down a well and rising from it. Slipping behind the veil and pushing them aside. The inherent hubris of painting matched with the negation of idolatry. The words Our Lady, Bitch, Saint, and Anne mean the same thing. Perhaps the selves operate as doorways through moments in time. Or maybe they are abandoned masks seen from the blank inside, she takes them off to see what they are. “Through the holes I see others. If I take the mask off and look at it from the outside, I see how others have seen me. In this sense, the removal of the mask is self-recognition.” (Flusser, p. 94)

Containing Multitudes: Anne Minich’s Head Series, 1974 – 2023, Commonweal Gallery, to Oct. 28, 2023.

Works referenced

Flusser, Vilém. Gestures. Translated by Nancy Roth, University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Proust, Marcel. Swann’s Way. Translated by Lydia Davis, New York, N.Y., Penguin Books, 2004.

For more Artblog coverage of Anne Minich, see

Roberta’s 2012 report on her studio visit with the artist;

Katie Dillon Low’s review of the show featuring Anne Minich and several others last August at Atelier Gallery;

Roberta’s 2004 studio visit with the artist.