From the moment I learned of the newest show at Tiger Strikes Asteroid, Martin’s End, featuring Ryan Scails and Andre Yvon, I knew immediately that the exhibition would have me in a chokehold due to its extreme visual and conceptual layering and the clear intelligence and speculative nature of the artists themselves. This prediction was correct, and I’ve had the privilege to become acquainted with the show upon many visits, each one better than the last.

I first met Ryan Scails at the Fabric Workshop and Museum during the summer of 2023 where he was working in the first-floor gallery that day. He had his head in a sketchbook and I became entranced by his artistic voice and the delicacy of his hand, as he drew beautifully-rendered studies of objects that appeared almost familiar but also unrecognizable.Learning that he is completing his MFA at Tyler School of Art and Architecture, concentrating in Fibers & Material Studies, I was deeply enthralled by what this artist might be creating beyond the confines of a sketchbook. It was clear from the start that Scails’s prowess lies in multimedia work, and the select few of his pieces in Martin’s End only scratch the surface of this artist’s capabilities.

Having opened on September 14 and running through October 21st, Martin’s End also features the works of Andre Yvon: another prolific artist– based in Brooklyn, NY, holding an MFA in painting from RISD– who also consistently pushes past the boundaries and conventions of their own medium, much like Scails has done.

Located at Crane Arts, Tiger Strikes Asteroid offers an intimate setting spanning a single windowless room replete with niches, quirky elements of the building’s original structure, and eight wall surfaces, perfect for displaying only the essential works that very carefully unify an exhibition.

Martin’s End “ponders image-making in the wake of the 2016 election and growth of generative artificial intelligence,” according to the TSA write up on the exhibit, where the title is an ode to 20th-century philosopher Martin Heidegger and what he deemed “the end of philosophy.” Within the exhibition as a whole, speculative proposals for the future of objects in the post-image and post-industrial age meet critiques on the current state of image-making and the importance of combining ideas, algorithms and manual process in the deconstruction and reconstruction of representational imagery. Through two distinct voices, the artists display prowess in hybridizing conventionally artistic, manufacturing, and hand craft techniques to create entirely new media and categorical blends between art, artifact, image, and object.

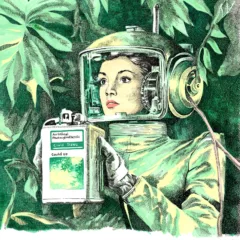

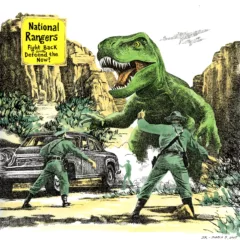

Even with the smaller size of the gallery, I was immediately enthralled by the largesse of the pieces within the exhibition. From first sight line at the space’s entrance toward Andre Yvon’s painting called “Untitled (Reality Winner),” the portrait’s gaze gestures to the right toward the intended flow of the 17-piece exhibition. Yvon’s gorgeous paintings – from a close-up of grass or a spider web to the portrait – immediately appear hyperrealistic, and upon closer inspection become mesmerizing studies on image making and reproduction through the layering of shapes, colors, and textures in acrylic paint on stretched linen. These large paintings, ranging from 24×32 inches to 56×42 inches, command the room with precisely-applied layers that appear to vibrate with frenetic energy. In conversation with Yvon, they state that “these paintings are built in layers using vinyl masks. Each color is [applied] using LPHV spray guns commonly employed for auto touch-up.”

Yvon hybridizes the materials of fine art, industrial design and manufacturing, and techniques both digital and manual, to throw convention out the window: “I paint from photographs via digital images so it doesn’t make sense (to me) to render forms using traditional techniques. I paint images of images.” The paintings contain conceptual depth that spans beyond the physical and visual realms, providing insight into their process of creation and expressing critique on contemporary image-making as a whole. Separating each tonal layer of a photograph in the readymade algorithm of digital software, Yvon then reconstructs the images layer by layer, manually adding each back onto the linen hundreds of times over. These works involve immense amounts of control and physicality, posing open-ended questions on the limits and potential innovations of an artist’s hand in creating imagery in present day.

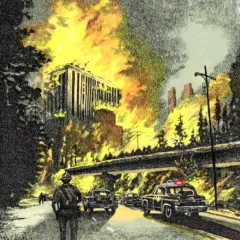

The result of Yvon’s additive process has allowed me to imagine the paintings as topographies of excavated strata: solid and void. Their paintings depict–in Yvon’s words–“absence; a landscape composed only of sharp grass, flowers with no petals, a dracula orchid that never dies, a truth teller, absent voice, a spider’s web blackened with soot after a house fire. The real subjects are always off screen.” We as viewers are forced to ponder what exists beyond the rectangular confines of the images themselves, and the significance of each particular subject. “Untitled (Blades),” for example, gestures to the toxicity of colonial lawn grass, its destruction of native ecosystems, and the allegory for greater spatial, environmental, and political ramifications of colonization.

My particular favorite of the collection is “Untitled (Iteration Camo)”: the “oddball” according to Yvon, the carefully abstracted work that portrays a singular image superimposed on itself to incite a sense of movement, illustrates the process of the rest of the pieces in their collection. Charlotte G. Chin Greene, curator of the show, remarks that their choice of placement, right at the start of the intended flow, resembles the beginning of a film in which the ending plays without context, only to be reprised at the story’s conclusion. Within the piece, I am able to clearly see the texture in the linen base due to a coat of silver-painted shimmer, which in turn becomes increasingly masked by the opacity in each layer of acrylic, allowing new textures to form through the act of compositing. The gallery lighting specifically highlights these moments toward the top edge of the linen, where the thin layers of paint appear embossed by those that are covered. The original image is distorted and manipulated in ways that the other source photographs are not, making “Untitled (Iteration Camo)” the reference point for investigating and understanding the more representational works throughout the rest of the exhibition.

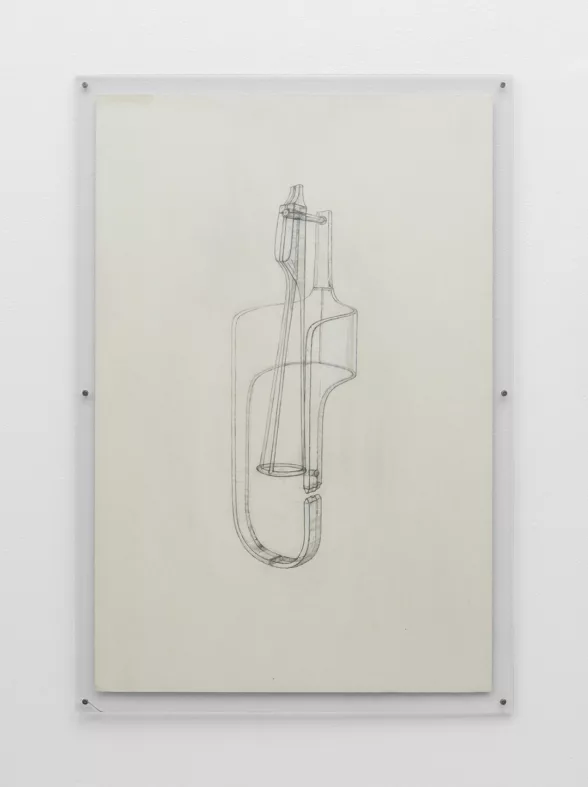

Where Andre Yvon’s practice intensively combines media and techniques layered into singular self-contained art objects, Ryan Scails’s work involves one consistent voice across varying media and multiple pieces, which act as proposals for the future of art objects and artifacts. Just as we now have access to mere remnants of ancient pottery and tapestries, these works made in fibers–both found fabrics and reclaimed wood paper product, and depicting glassware and metal hardware– provide speculations on what might be found in scraps in far futures. Scails expertly deconstructs industrial design and engineering technics, pointing us toward an imagined context of how we might create and view art and objects after industry collapses and images end.

The curation of Scails’s pieces provides a similar narrative as Yvon’s trajectory, with a first glimpse of the story’s ending through “Lichen,” a stand-alone sculpture placed immediately to the left of the gallery’s entrance, and the only dyed piece in his body of work. In the beginning and middle of Scails’s narrative, his simultaneously strong and subtle artistic voice becomes clear: with muted color profiles based in natural undyed fiber, his works on sheet product and in fabrics converse in tension and balance with Yvon’s intensely hypnotic and colorful paintings, providing frequent reprieve. Scails’s delicate “Untitled” drawings proffer “speculative technical objects and ‘anti-exposure units,’” per the exhibit’s write up, that blur the lines between artifact and art-object in two and three dimensions. These seemingly familiar but ultimately nonsensical units are beautifully rendered in graphite, oil-based pencil, and china marker on paper, appearing as glassware that resembles scientific equipment. The delicacy of the original drawings directly references the fragility of what they represent.

Not only did I rejoice in the beauty of each of these objects, drawn in a technique clearly reminiscent of architecture and industrial design documents, but I was equally ecstatic about the mounting techniques: each task board– a sheet material made from forestry wood and resembling paper– slightly protrudes from the wall in an encasement of two acrylic sheets and metal hardware. Scails was scrutinous in his display, and also in his intent for how this technology informs the conceptual and visual journey of his collection: the acrylic sheets act as slides to be viewed under a microscope, where the imagined objects are cells–vessels for movement and flow, but also the modular beginnings of entirely new creations. Through these works, I am able to contemplate the difference between representational drawing as art object, and as artifact.

In the same vein, Scails masterfully manipulates fibers to create functional objects: the “Dye Carriers.” Each jar displayed is filled with the very dye from which the rest of the collection–save for “Lichen,” is devoid. The pieces, made in reclaimed fabrics, allow us viewers to conceive of a context without industrial design as we know it, where reclaiming material is central to new ways of creating. Where Scails uses fiber arts to provide strength in object-carrying artifacts, he in the same turn proves the medium’s range in its ability to stand singularly as a sculpture in “Lichen.”

I was most excited to view this piece and was struck by the careful intentionality of Chin Greene’s curatorial choices, where the “Lichen” is able to be viewed frontally in its full singularity only at the very end of the show’s progression. After much anticipation, I simultaneously felt tension and relief approaching the indigo piece from the far end of the gallery, where “Untitled (Blades)” hangs alone. A composite sculpture made of multiple modular “cells,” a recurring motif in the collection, “Lichen” is mounted on a cantilevered system completely suspended from the wall. The careful display method allows the piece to filter light and cast perpetual shadow onto the large white surface from which it protrudes. Within the piece, the modules are pulled together and stay in tension through a jettison stitch, awaiting physical release of the ties that bind them. “Lichen”’s hand-dyed canvas speaks to its codependency with the “Dye Carriers” and alludes to a future of increased manual skill, in opposition with the fashion design industry and its contribution to mass global waste. Using media and techniques that have otherwise existed for centuries, Scails’s work transcends our current possibilities of creation into the unknown: where will technology find its limits, and what will we lack?

While these two artists’ collections within Martin’s End are seemingly contrasting on the surface level–when viewed only as visual art objects within a gallery space–their critical voices ring in eco-apocalyptic unison: the artists ask each of us to scrutinize contemporary artistic practices and their ever-expanding boundaries beyond convention, blending with techniques from beyond the fine arts, and to imagine what can be made–and eventually destroyed–beyond our lifetimes. What is possible within our current time, and what could be next?

The final day of the show is Saturday, October 21st, from 12pm-6pm, in which Tiger Strikes Asteroid and other spaces within Crane Arts will be open to the public. I hope that interested visitors decide to make appointments to see the works before then as well. Martin’s End is a spectacular show with multiple layers of technical prowess, artistic voice, refutation of conventions, and strong conceptual bases. This is certainly an event not to miss.

About the author

Martina Merlo is a multimedia artist and designer living in Philadelphia. With a background in time-based media art, architecture, and multi-form prose, Martina loves telling stories through music, design, video, printmaking, large-scale installations, and of course writing.