“We’re All Here But We’re All Dead”: An Interview with Jacob (Chris) Hammes about the Closing of Pilot+Projects and the Acceptance of Mortality in Artist-Run Spaces

Author’s Introduction

Pilot+Projects was a gallery, studio, and project space in Fishtown, Philadelphia. Opening in 2016, the space was forced to close due to rising rent attributed to “market rates.” There has been a rotating cast of characters from the founding members to the ones who packed up everything, but the one mainstay has been Jacob C. Hammes, or Chris as his friends call him. Chris, is an artist, writer, and musician who has been the driving force behind this for-artists-by-artists space.

In its many years, Pilot+Projects was host to gallery shows, performances, and installations by such artists as Stephen Lapthisophon, Shona McAndrew, Jim Strong, Paul Ramirez Jonas, Michael K. Taylor, Sarah Knittel, Kristen Neville Taylor, and Academy Records. As Chris describes, it has changed so much over the years but one thing always remained a central tenet, to uplift and give opportunities to Philadelphia artists. That remained true until the very end. Myself and almost 100 other local artists had the good fortune of being welcomed into Pilot+Projects’s last show – Epilogue. A bookend to their first show, Prologue. For Epilogue, it was a wonderfully generous space where anyone who showed up could hang up their work. Even folks who showed up with works during the opening were promptly welcomed in, and their artwork displayed. The opening was not a funeral but a glorious last hurrah. Apparently, it ended with 5 a.m. karaoke (“Just to say we did it”).

We all gathered in the small space and spilled out into the streets of the rapidly changing neighborhood. Sad, happy, tired, and (some of us) drunk, we closed out the space with a burst of community. There was no finality, we all wondered what would happen next. What would happen to all the DIY galleries, artists studios, and community spaces as rents rise and developers raze whole neighborhoods in favor of condos, bong shops, bars, and restaurants? Where does art go when it is no longer needed by the people who deem where things go?

Chris generously talked for an hour with me the week of their move out from the space. We sat down among an array of trash and artwork, but mostly things that fall somewhere in between. He began by speaking about the process of hanging this final show.

Jacob (Chris) Hammes: This (Epilogue) is probably the first show where I was super strict, everything I said to people was like, “Don’t make my life harder than it already is right now.”

I asked him about these beautiful, hilarious, and heartbreaking Google forms that were sent out to the participating artists. The participants were asked to check boxes acknowledging that the folks running Pilot+Projects were “very sad and overwhelmed” and that they “care about their artwork and will not leave it there”.

I honestly wish that I had thought of that a long time ago. Oh, what, how does it hang? Is it, uh, nails, screws, pins? Does it sit on the floor? Does it sit on the shelf? Are you bringing the shelf? Right. You know, all of that stuff. I wish I had this form prepared so that I could just send it out and get all the feedback and get all of the, you know, title, date, medium, everything in the correct format.

Pretty much without fail, in the hour before the opening, I would be… in the back, trying to get my shitty old printer to print out a checklist, a gallery map, the press release, and the poster, and then put them together in those binders so that people can walk around with them.

Lane Timothy Speidel: Are there other – I don’t know if you’d call them members – other participants in Pilot+Projects who help run the space?

Chris: Yeah, so when we first started there were four of us, and then pretty quickly, two people dropped out within the first six months.

Lane: Yeah, that happens.

Chris: When they’re like, oh shit, this is a lot of work. Then it was me and Jen Nugent for three years co-directing, and a bit later Olivia Williams as curator’s assistant. And then, I think maybe three, four years ago, Jen moved to St. Louis. So I’ve just been kind of doing the whole directing by myself. My other studio mates, are helping out with a lot of the setup, installations, and openings, Michelle Harris, Maria Stracke, and Victoria Ahmadizadeh Melendez. And then also Maria’s partner Alex Wermer-Colan helps out sometimes.

I worked in exhibitions for a really long time before I started doing this. In Chicago, at this place called the Hyde Park Art Center. It was a community art space. They had contemporary art exhibitions and local, national, and international artists. We went from having exhibitions and classes to outreach in public schools and doing a residency program. And I mean the projects just got bigger and bigger and bigger. I was lucky enough to work there for seven years. I learned so much about how to do something really, really scrappy, just, very little budget, no time, no staff. I was the only preparator, I was the only art handler, I was also the Media Technician, and my boss was the Director of Exhibitions. She was the only one doing that. Every department was like two people, so we all worked constantly. Pitching in, because we believed in it, you know? People were – if they saw me struggling to get a show up, they’d grab a paintbrush and a roller and help me paint the walls and all that stuff.

So that’s the kind of attitude that I brought to this, I think. And that didn’t always work. Because sometimes, I’m not good about verbalizing my expectations to people. So, not everybody can just do that, like, go, go, go. That kind of constant motion that I am sometimes good at doing and sometimes really bad at doing.

When we opened up, I had a manifesto that I wrote.

Lane: Oh, really?

Chris: It was because we got a grant to open up the space from Temple University, the Kabakov Award. Because we had all just graduated from the Temple Sculpture Department. So I had written out this very specific thing I wanted to do. And it had to do with noticing the way that things were being done in Philly. Comparing them to the way things I was seeing in Chicago and other places. And then trying to figure out what I thought worked and what didn’t.

I didn’t want to ever run a member space. We were supposed to be a curatorial team. That’s what we were supposed to be. Part of that was, you know, the impression I got from talking to people that were involved in member spaces, who said that sometimes the organizing was like – this is my month, I do whatever I want, don’t touch it. Now, this is your month.

Lane: Okay, I see.

Chris: I wanted it to be much more collaborative. So I was like, okay, we’ll be a curatorial group. And if somebody drops out, we never went searching for another person to take their spot. So that’s why it dwindled down to just me. Because I was like, fuck. I don’t think I know anybody really that would want to jump into that, as a partner, you know. But that also meant that I got really burnt out. And, there were long stretches of time where I thought, I need a bigger studio. I don’t need to do exhibitions right now. (Meaning that he would use the whole gallery as his studio.) And if it was a member space, I probably wouldn’t be able to do something like that.

We’d just have to do a show every month or every two months. The last few years have been different than what it was in the first few years because there was a pandemic. We didn’t do any shows. And then when we came back the attitude that I had about it was like a 180. Because, originally we were trying to do solo and two-person shows only. Another philosophical idea we had was no giant group shows. Because I was like, you don’t have enough room to let any of the work breathe, you don’t get to see more than one piece by an artist, and I’ve never really felt like I know what an artist practice is if I’m just looking at a single work.

Lane: Right. That might be a great piece, but what’s the other thing? What’s the context?

Post-Pandemic Group Shows to celebrate and reconnect

Chris: I was like, okay, we’re gonna do two-person shows max. And that wasn’t a hard line, that was just what we tended to focus on. After the pandemic, it really felt like we all needed…opportunities to come together in big groups and reconnect and celebrate some sense of community.

Lane: So it was like, we’re all still here, we’re alive.

Chris: It was a 180 for that alone, because I started feeling like actually I’m not against doing giant group shows. I thought maybe that’s the best way for us to heal. So the first show when we came back was with the Iglesias Gardens, https://iglesiasgardens.com/ which is up the street from us. And there were dozens of artists in that show. It was a giant party, a multi-generational community of people. There are young energetic activists and some older folks that came in, came in like 10 minutes before the show started, asked for a chair, posted up all night, and just sat in a chair and held court. Right. And I was like, this is really awesome, everybody, this community is really cool. We had Aztec dancers come, and the crowd just spilled out into the street. There were performances, there was food and live music. That was like, okay, we’re back. We feel good about maybe going in a different direction.

And then I started getting involved in projects of my own. So I had to go, “I need the studio again.” It was different from what we were doing before the pandemic. Before it was every five weeks, there was a new show. People are coming in to see the show. Then I close the doors for two months and work on my own stuff.

Lane: It sounded like you grew less rigid. Like, the space can change to suit the needs. Rather than, the expectation of showing creates the parameters of the space.

Chris: I think opening up the space, coming in with a certain amount of ego-driven attitude, like, I want to work with the best artists. And I wanted to have really tight shows. Yeah, and then it was like, you know what, actually there’s this community of people up the street. They make art, it might not be exactly like what I’m excited about, but they’re excited about it. And if this space could be used in that way some of the time, that’s way better than having it be some kind of exclusive thing.

Lane: Well, I thought it was super lovely and generous that as the “walls are coming down,” anyone who comes through the door can put their work up. I thought the opening (of Epilogue) was really beautiful and also all the conversations with people coming in and out. I was making a lot of connections to folks who I’ve only seen around. And seeing everybody’s work together, it was really something special. How many artists were in the show?

Chris: I lost count. I think I accepted like a hundred artists. At the opening, I definitely had a hard time at first because I was starting to feel like as soon as people started showing up, I wanted to sweep the floor one more time. And now I don’t get to because there are people here, but fuck it! I don’t need to sweep the fucking floor again. Ever again. So I started to get sad about it. Just stuff like that, like the little things made me sad. We were here until like 5 in the morning.

I had had so many conversations with people about, “What are you doing next? Why is this happening? Where are you going?” And they wanted to know details, and I was kinda tired of it. I was tired of answering the same question over and over and over again.

Lane: That can be really brutalizing.

Chris: Yeah, and then I sat down on the stoop and Alex Connor was here. There was a moment when he was like, “What’s your favorite part about running a space like this?” Or he might have said, “What are you going to miss the most?” And we were right about to sit down on the stoop. There were all these people standing out there and I was like, “It’s this right here. Just this. Sitting right out there talking to other artists, connecting with people on any kind of subject we start talking about.” And it usually wasn’t about art. It was just about people’s lives. And about, maybe a TV show they saw, or maybe the music they’re listening to.

Lane: Yeah, I’m trying to think at the opening. Certainly, we did talk about art. But I feel like most of the conversations, I can recall, were not about that. Or they were tangential, you know. But we talked about movies and childhood stories and stuff.

Chris: The opening was a little bittersweet. We did end up… I’m gonna say it was 3 or 4 in the morning. We all lay down on the ground in here. And just pretended we all died. And that was just an idea that I had, and then 10 minutes later we were doing it. It was like, hey, what if we all lay on the ground and pretended we were dead? And then… You know, blast that out (by posting a photo to Instagram) to show people that it’s five in the morning and we’re still here. But we’re all dead.

Lane: We’re all dead. That makes sense, I mean, in a way, to physicalize this death. I mean it sounds like you’re having a lot of grief. And I think a lot of people are having a lot of grief.

Letting Go of Your Stuff

Chris: Oh yeah. It’s been a weird week because I just finished this giant Mural Arts project:

(https://whyy.org/articles/prevention-point-love-lot-kensington-harm-reduction/).

I’m not quite finished with it. But I’m finished enough that I can walk away until September and come back and touch up some things. I was finishing that, and there are all these news organizations trying to talk to me about that. And the whole time I’m thinking, “How the fuck am I going to move my stuff out of my studio?” It’s just, you know, I’m a bit of a hoarder. I see something useful in the trash, and I don’t want it to go into a landfill. So I take it, thinking it’ll be a part of some art piece, or maybe I can repair it, use it, and then if I don’t…

Lane: … someone else will need it.

Chris: So that’s why there were tables and tables of junk out there (referring to the overflowing tables and boxes of freebies on the sidewalk the day of the opening). And I probably have another six tables full of junk that I could be getting rid of.

Lane: Yeah, well, I feel like that is also like a classic death thing. When we go, what’s left is mountains of stuff.

Chris: There’s definitely a lot of times when I think about the possibility of dying. My first thought is, “What’s gonna happen to all my stuff?” Because my partner will get stuck with going through it. And she’ll probably just do what I did, give everything away. “See ya!” It’s weird to have such a feeling of, “I need to know what’s going to happen to my stuff when I die.”

Lane: No, for sure. Last year I was feeling super depressed and I was like, I’m just going to make a living will. I’m just going to make a will, for fun. And actually, it made me feel a lot better.

Growing up in Iowa on a ‘goat ranch’

Chris: Yeah. for me, I think it definitely comes from my Dad, and from growing up lower-class. I don’t even think of it as hoarding, because it’s all stuff that does have a use, not just to me, but to other people. Buckets of hardware, buckets of nails, and screws. Hmm. My dad would have so much of that stuff that he would build a shed and put it in there, and then before he used it all up, he would build another shed to put more of that stuff in there. The property that we have in Iowa is like, all of these different locations where you have tools and hardware and lumber and scrap metal.

Lane: Yeah, that’s super exciting that there’s so much potential.

Chris: But that’s also much easier to do in a rural environment, where at least, it’s six miles from the nearest town where they live. A mile in each direction to the next house.

Lane: Wow. Is that where you grew up?

Chris: Yep. I grew up in Iowa. We weren’t farmers. Mm-hmm but we referred to it as the goat ranch ’cause we had goats. We had goats and occasionally other farm animals. But, we never really had enough land to be properly a farm. We never butchered the goats or even milked them. They just were there. They were terrible pets. Baby goats are the cutest thing that you could ever see.

Lane: Oh my gosh.

Chris: Yeah, but then when they grow up, the males piss all over themselves. Like as a pheromone or like as a scent thing? Oh yeah, they do it and they stink, and then they headbutt you if you like, get too close to them. But when they’re babies, they’re just trying to find stuff to climb up on and jump off of it. They climb up on the table and then they twist their bodies in the air. I have a lot of fond memories of that.

Lane: That’s so sweet, seeing the place full of life. But there’s also a lot of death that happens around farms like that, right?

Chris: Oh, for sure. Sometimes it’s like another animal comes and kills a chicken or something. Right. And the dog finds the chicken. Cause the dog didn’t notice until the chicken was already dead.

Lane: Yeah. I mean, life necessitates death, right?

The End of Pilot+Projects is not a death but a closure

Chris: Yeah, which you don’t see very much in the city. I’m trying to think of a good example where you see it. I mean, I’ve been thinking about this place (Pilot+Projects) as being dead, like we killed it. It’s not accurate, I’m being dramatic. We always intended that if we moved, or if we changed… our mission, too drastically, we would just change the name. But we would consider it done. We never really wanted to pass it off to anybody. I saw how much energy goes into that in other spaces. Where you’re constantly searching for new members. And sometimes that doesn’t work out. People have different expectations when they come in. So we never were trying to figure out how to pass it on to other people. We thought, “When we’re tired of it, we’ll stop doing it.”

Lane: Yeah, so much effort. I love that kind of acknowledgment of mortality. There’s so much effort that goes into longevity. It’s like, okay, when we’re gone, what are these people going to be? How can we help these future strangers?

I think that’s really beautiful. Immortality, that’s just a fantasy. It’s not real.

Gentrification

Chris: Yeah, I wish we could’ve ended on our own terms…I think a gnat just flew by my nose. Gross. (There were flies and gnats wildly roaming in and out of the sliding door and around the trash bins.)…Anyway. Seeing all the buildings popping up around here that used to be empty lots. Seeing things get knocked down. Seeing all of these new people come to the neighborhood just to go to these bars that are across the street. Okay, this neighborhood is rapidly, rapidly developing. There’s no way we’re going to be able to be here when that starts. Every year we were, “Okay, we know that the landlord is going to ask us to pay 5% more.” Because that’s what apparently happens every year. Our lease contract has that, and the property manager says it’s “standard.”

Lane: Like no matter what number, they would have said,“That’s standard practice.”

Chris: When they doubled our rent, they said, “This is the current market rate.” And I thought, “You could have tripled the rent and you would have said the same fucking thing.”

It’s not a real number. It’s based on what other people are paying around here. That doesn’t mean that this particular building is worth that much. Especially when it’s crumbling as much as it is. And the pipes are leaking, and there’s rats, and…nothing has been done to improve this space, and it gets worse every year. Every time I ask something of the landlord, I have to go through the management company, and then they ask the landlord, and then the landlord says, “That’s not a priority,” or they just say no. And I’m like, “You deserve this larger payment every month?” This is what’s wrong with capitalism in general.

The sense that, “I own it, so I can do whatever I want with it.” Implying that you’re doing something to earn that? You’re not. You’re just owning it. You’re doing nothing to earn it in the traditional, fucking, dictionary definition of earning something. It’s an investment property that you hold onto until it is worthwhile. Until you’re gonna –

Lane: – Knock it down.

Chris: Yeah. They (the landlord) would never tell us what they have planned, like if they’ve got plans. They could have planned this two years ago, that they struck a deal with somebody and, in two years, we’ll have this space available for you. But it also seems likely that… they thought “We got them (Pilot Projects) over a barrel.” Because they don’t seem like they’re making any moves to go anywhere. And I didn’t have anything planned.

We thought for a minute there was going to be a bong store.

Lane: So, no bong store?

Chris: The owner is not ever going to say anything about what it will be. I’ve not tried to ask him. He’s a person that I see around town, and he pretends like he doesn’t know who I am.

Lane: Oh weird, like he’s your therapist or something?

Chris: Sometimes I see him at a bar or something. And he pretends he doesn’t know me, you know, like, it hurts his eyes.

Lane: Oh my god. Do you think he feels…uncomfortable?

Chris: He knows I don’t like him. Yeah. To be honest, I probably do the same thing, for the most part. I don’t make any effort to try to speak to him.

Lane: Right. It’s literally like the antithesis of any kind of community, or any kind of relationship.

Chris: No matter what they say, they’re just in it for the money. I’ve talked to lots of developers and they all know how to say shit like “We want to have a community.”

Lane: Then go back to where you live and have a community there!

Sunflower Hill and talking with developers

Chris: The longer story about Sunflower Hill has to do with the land owners, which are not the people who were running it most recently. It’s the guy who owns the property. Before the pandemic, it was one company that owned every piece of land on this block except for our building. They were trying to build a four- to five-story spaceship-looking condo building and we saw the renderings of it. They showed us what they wanted to build. And they wanted to wrap around the whole block except for this building. And then they tried to buy this building, probably to knock it down, so that they didn’t have to build a building around it.

The reason we know them is because Jen and I were here one night and these two guys stumbled in drunk. And they were like, “What is this? Oh, you guys are artists? Art gallery? Guess what? We’re gonna build an artist community. We own all the land around here, and it’s gonna be an artist community.” And I think that they thought we were gonna be blown away by this idea.

But instead, we were like, “What the fuck does that even mean? You’re gonna build an artist community in a condo? How is that gonna work?” And then, one of the guys, who I’m not gonna name, said, “There’s no artist community in Philly.” And at that point, Jen and I looked at each other, and we started screaming at this guy like, “Who the fuck are you?”

Lane: Oh my god. That’s the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard. Do you think he really believed that?

Chris: I think he just didn’t know any better. So at one point, they were like, “Oh, can we have a meeting with you guys?” Our thought at the time was, “Who are these fucking douchebags?” One of them looks like a Trump brother, hair slicked back, suit and tie, walking down the street, smoking a cigar. He’s a 30-something, wannabe Eric Trump or something.

We were naive and didn’t think anything of it. We don’t know or trust these people, but we’ll meet with them, right? Thinking, at best we can help them to at least understand what it is they’re saying, right? And then we thought, well, if there’s any way that we can, I don’t know, convince them of what to do with their massive amount of money, then maybe it could be helpful for us, right?

So they were, “What kind of things would be a part of an art community?” You know, like they didn’t know.

Lane: Oh my god. Oh my god.

Chris: We said, having an exhibition space where you would show local artists would be a good thing. Having low-income housing for artists would be a good thing. Having an artist residency would be a good thing. And then they went, “Wait, What’s that? What’s an artist residency?” So we explained to them what that was. Yeah. And they did not seem to like it at all… they’re like, “What’s in it for us?” An artist residency would be a thing where you invite an artist in to do a project or they invite them in for time to work. You give them a studio space, and then they work there. And maybe they’re local and they need a studio, or maybe they’re from out of town, and you give them a stipend.

And they’re thinking, “There’s no money for us in that.” And then Jen said, “Oh, but some residencies ask that you donate (your art) to the residency, and then you can build a collection.” And when she was saying that, I was behind her going (motioning for her to stop). Boom. Because I saw their eyes light up – that would be how they make money off artists. Fuck them. Those are the worst kind of residencies. That’s not a thing that I would ever want to go to. Whatever you make there, they expect you to donate a substantial portion of it, or a piece that you’ve made, and then they build a collection that way. It’s sort of a scam. But anyway, they got excited about that. And then they were, “How can we get you guys involved?” And we had thought about that a little bit. And we were, “Well, you need to give us some money to administer an artist residency. You need to put this much towards the artist, and blah blah blah.”

Nothing happened. They dug a big hole

It never happened, but then we did discover that they were using that as talking points later on, telling people what we said to them like it was their idea. We got fucking scammed. We didn’t realize that we were doing a consultation. That we could have charged them a ton of money. We gave them all of our ideas. They had no intention of ever doing it, but they wanted to be able to say it to other people to convince people in the community that that’s what they were thinking about. Yeah. We felt like chumps because we helped them to clarify some of their verbiage that they were telling people.

They never built the buildings but they dug out a big hole. And they destroyed a lot of our stuff in the process. We had this fun community of neighbors that would gather outside around a bonfire and then it got bulldozed. Jen and our upstairs neighbor had been growing sunflowers in a raised bed. They destroyed all the gardens that we had in this ground-level grassy lot. They knew we were really pissed off because we called L&I, and it shut down because maybe they didn’t have permits to dig.

They stopped digging. Pretty much immediately. Jen had a meeting with one of the guys where he was, “What can we do to make it better?” And she said something like, “Plant some fucking sunflowers. You just destroyed our fucking sunflowers, so plant some fucking sunflowers.”

And they did, like a year later, and then started calling it Sunflower Hill. But that’s gone now too. Because the dude sold his share of the property. I think the other dude still owns it. But it’s a big dump yard, just piles and piles of dirt and rubble now. Part of the initial design was to do a giant five-story condo there. The amount of changes that we saw happening in this neighborhood. It really felt like we weren’t going to be able to stay here. And, I wish that we had been the ones to decide it. Instead of just being told, you have to pay twice the amount of rent. Which is a … it’s a way of making us…

Lane: Like forcing you to make a decision.

Chris: I wish we could stay in this neighborhood. But, looking around, it feels like, there’s nothing affordable around here.

Lane: There used to be more art spaces. There are still a few, across the street.

Chris: We’re pretty close with the guy who manages those apartments, and started MIA (Mission In Arts). So he… Nick Spiro, I call him the Mayor of Fifth Street, because he walks around and shakes everybody’s hands. Right. Knows everybody. Walks in, you know, whenever I have the doors open. He’s got big plans for the basement (of the 1720 N 5th St building). He started a gallery, they’re now doing art classes, they have a ceramics studio. They have a printmaking studio, they do painting and stuff. It’s all in that basement. That was his vision. When they were building it out, he invited me in to see what they were doing. He was like, “What do you think about this as a gallery space? Should I put drywall on the ceilings to cover up the trusses?” I said “Nah, leave it raw.” Cause, you know, that’s what you expect when you walk into a space like that. But then he did it, he covered it up and it looks really great. I think maybe I was wrong. Maybe.

A little history, some strained relationships, some fun

Lane: Are there any… memories, or anything? Funny things, sad things, silly things, over the years, come to mind?

Chris: Not every show was as exciting as it could be. And not every show did we put in the amount of energy that we should have. We had some really silly ideas when we first opened. We thought at first we were going to try to do a dance routine and videotape it at the end of every show and call it a Thank You Dance.

Lane: Oh wow, did you ever do that? Oh my gosh, that’s amazing.

Chris: We did a few. And I kind of wish that we had just done them all. But it was always so hard to choreograph. I mean, when I say choreograph, we didn’t really choreograph. We’d be like, all right, I’m gonna go in my studio for ten minutes and think of five dance moves and Jen would do the same. And then we’re gonna teach them to each other. And then we… Oh my god. I mean, some of them are on YouTube…

Lane: I wanna find one.

Chris: I think some of the sad things involve some of the interpersonal relationships that were strained in the process of running this space. Some close friends are no longer close anymore, and that’s a real bummer. It was stressful doing this stuff, and trying to do other stuff with your life that isn’t this, committing to other things, it was hard. It bums me out.

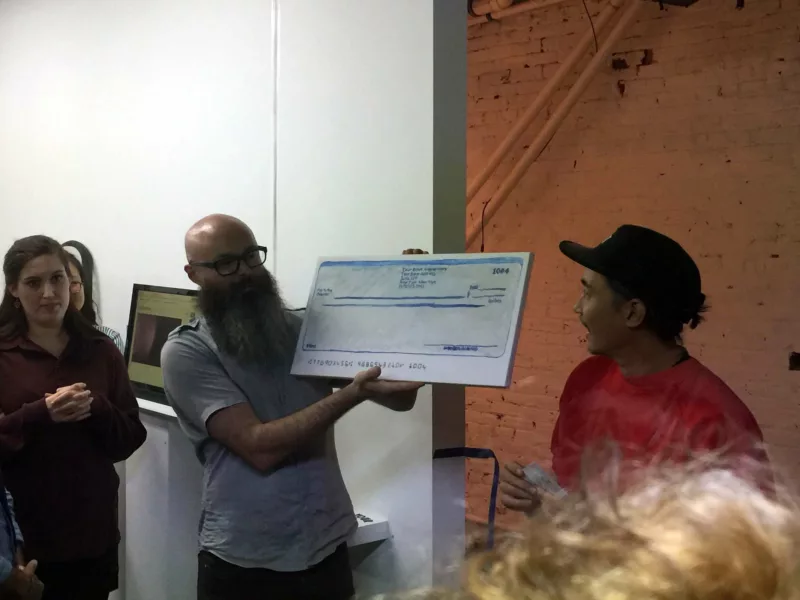

The Readymade Competition

Chris: But some fun things. One of the shows that we did that I really loved was the readymade competition.

We asked everybody to make a readymade, and compete to make the best one. There was an entry fee of, I’m not sure, $10 or something. Yeah, we got $700, because we decided we were gonna give out prize money. So we had an award for Best Readymade, an award for Worst Readymade, and a bunch of other awards. There was one award for best potty joke. Because, you know, the urinal.

Lane: Right, right, the Duchamp “The Fountain” piece.

Chris: It was the 100th anniversary of “Fountain.” So, some people riffed off of that in funny ways. There was one (award) for most market-ready. Which meant the one that looked the most like it could be sold in a fancy art gallery.

We had judges from the Barnes, the PMA, and the ICA.

This was with an artist and curator in Chicago named Brandon Alvendia, he’s one of my closest friends, and I knew that he and I would be good at doing this together. If it was anybody else that approached me, like some unknown person, I would have been, there’s no way that we can pull off something like that. There were 70 artists in that show.

Lane: Okay, so Epilogue, the last show, has a little bit of a precursor?

Chris: Yes, but it was more like a curatorial challenge. What’s your version of this well-understood and, sort of highly intellectualized art style rhetoric? Just find an object, call it art.

Lane: Oh my god, that is genius for readymades too. That’s so hilarious.

Chris: The one that won was an artist who just sent us a bowl and two bags of candy. M& M’s, and Skittles and called it “S and M.” It (the candy bowl) was sitting on the desk, and the judges, they walked all the way around the room together, tried to discuss which ones they thought were the best. And then they ended up over here just munching on the candy. And I was like, “Oh, by the way, that’s a readymade as well.”

And they were, “That’s the best one!” Because they didn’t know. They loved the hell out of it. They thought it was hilarious. So that got best readymade. And then the worst readymade was…

Lane: Which also deserves a prize! Because it’s like, what’s the worst readymade?

Chris: Well, something that you’ve made. Yeah. So it was an artist that had made something with yarn. It was a tower. Hundreds and hundreds of little knots are sewn on it. And we’re, “That’s not a readymade.” By someone who maybe didn’t know what a readymade was.

Sound art, experimental music noise music

Chris: So that was a really fun show. My background is in sound and experimental music. So I always wanted to do that stuff here, but having people live upstairs made it, really not a good idea. But the couple times that we did… Actually, Jim (Strong) performed on the same bill. It was David Moré, Jim Strong, and Yixuan Pan. It was the most diverse range of sound stuff because I knew David’s was going to be this giant analog synth, as loud as humanly possible. We turned off the lights, and he had little amps that he plugged into the bigger amp and they started smoking. I was doing documentation and I ran over, “Those are smoking.”

He’s, “Yeah, I know they do that. That’s what they do. I buy a new amp every time.”

So it was Jim sitting on the floor, with his strap-on noise instruments. And then at one point he stopped playing. He took off his socks and started doing weird little movements. And then I think we couldn’t quite tell when it was over, so he was, “That’s it, it’s over.”

Pan was in the glass department of Tyler and had made blown glass pieces that fit the size of her mouth and blew air into a glass of soapy water. And they were to whisper a love letter into it. And it was a vessel that had this… perfect mouth-shaped thing and she just whispered. It was so, so quiet and then David plugged in, we turned

off the lights and it was the craziest.

Lane: Wow. That sounds amazing.

Chris: I felt like such a good curator then. ’cause Jim did a really weird one. Pan did a weird one, but the quietest, most sort of beautiful gentle thing. And then David did the most aggressive noise music.

Lane: He blasted everyone’s hats off.

Chris: Yeah, and nobody was expecting that. They came out for a noise show, and Jim was kind of noisy. David’s really, really noisy. Pan’s was like… almost nonexistent.

Prologue and The Crying Room

Chris: Our first show? Prologue? I remember when Zach Rawe and I were talking about what artists we were thinking about. Alex Jovanovich was somebody I was thinking about. He’s a New York artist, that I know from Chicago. And he’s got a very particular look. Just doing a Google image search, we found a picture of him. And then Zach was, “Oh, I was thinking of Eric Rushman.” And I know him from Chicago as well. And I was, “Wait, are we trying to pair these two guys together because they look the same?” They’re both gay men with a very weird-like, almost 1950s rockabilly style. I mean, I think their work would look good together, but also that’s kind of funny that they have a similar personal appearance.

But then the show was really, really good. It was pretty sparse, and Alex had a video here (gesturing to a small room connected to the gallery). And then every show that we did, it was kind of like a version of that. Kind of sparse on the walls, a single artist in the main space and a single video artist in the other space.

Oh, by the way, this room, after we had done three or four shows, we started calling this the Crying Room. We used to call it the Crying Room, because the first four or five pieces that we showed there were so emotional. People would be, “Wow, that was really emotional and powerful.” And we were, “Yeah, that’s the room where you go to cry.” This was a big part of the curatorial philosophy. I was, “There has to be a permanent place to see video.” Because most places don’t do that. But then, during the pandemic, I turned it into storage.

Lane: I mean, I’ve definitely used the Black Box, the screening space in Vox Populi, to go cry. Cause no one can see the tears in the dark.

Chris: That was a big part of the mission too, not just like a monitor on the wall with headphones. We put speakers in there. And it was also a really good way to get slightly more bigger name artists to be in the show. Because they can easily just send you a Vimeo link and tell you to download that.

Lane: Right, and they’re, “I’m in Berlin.” or whatever.

Chris: Yeah, they’re “I got five shows this month, here’s a Vimeo link.” Right. So secretly we were thinking, if we have any celebrity art star connections, we should be using their celebrity to help out younger artists that maybe need it.

How can we invert the kind of art star expectation and be, “No, it’s actually a solo show by this Philly artist.”

Lane: I love that.

Chris: We try to do some sneaky shit, by the way. Like, people would be, “Oooh, Paul Ramirez Jonas is in the show?” Yeah, he has a video. He’s a nice guy that sent us a video link.

There were times when we saw ourselves taking ourselves too seriously, and then we would try to do something to counteract that. It didn’t always work. This last show, I was really enjoying writing the press release. Because it was, “I’m gonna drop all this academic language that I’ve been hiding behind for all these years. Just throw it out the window.” Because I always had this attitude like I didn’t want to give too much away. I wanted it to be written in a way that was intriguing enough to get people to come in. Not give the whole thing away where people feel, “Oh, I know what it’s going to be like.” So it’s trying to write a line of subtlety.

Lane: Like a good movie trailer.

Chris: I’m done with that for right now. I’m gonna write this D&D (Dungeons and Dragons) campaign of Warrior Tenants versus Black Magic Wizard Real Estate Developers.

[Link to Epilogue Press release]

Lane: There needs to be more, D&D vibes in everything. Do you have any – besides not being able to end on your own terms – regrets?

Chris: Regrets?

Lane: [While Chris is contemplating this, some artists come by to pick up their artwork from Pilot Project’s last show. I asked them if they had any last words for Pilot Projects and they briefly jumped into the conversation.]

Jon Weary: It’s sad to see it go, tons of good memories. As a person, I saw a lot of changes in this neighborhood over the years. And Pilot Projects was here for such a long time.Whenever things like this come to an end, it’s kind of a wake-up call, to not to take that stuff for granted. It’s what makes Philly unique? Like, artist-run galleries. Viking Mills was such a hub for so long.

Lane: Yeah, I used to go there as a teenager when I first moved here.

Chris: Fuck, I can’t imagine what that was like then.

Lane: I remember going to this crazy party and being, “Okay, this is a warehouse. I’m learning what a warehouse is.” You have to make your own walls.

Chris: You might be in danger of various types at all times.

Lane: Right, there were people making out everywhere.

Lane: [The three begin talking about going to Karaoke together. Chris talked about how singing the Cranberries and the Beastie Boys felt good. More artists come in and out and Chris greets them and addresses the intricacies and logistics of all of his ongoing relationships and potential projects with them as they pass in and out of the space for the last time. Alone again, he picks up a lost thread about a group of artists he interacted with as part of a Mural Arts project. They have been working on a project called The Kensington Storefront, and Chris was really impressed by it.]

Chris: These artists that I was working with on this project. They just called it the storefront, it was on Kensington Avenue.

Right in the middle of the opioid crisis. And it was art-making activities. That was the whole thing. These artists that I have been working with at Prevention Point are involved in it too. Mural Arts stopped funding it, and then it closed. But they’re getting funding from other places and supposed to reopen it. The idea is, it’s a building you can walk into and sit down and make art. And no judgment about what kind of drugs you might be on or what kind of situation you might be in. That’s beautiful. I’m hoping to get involved in that because I wasn’t even really aware of what they had previously done until I started working with these artists. Yeah, it’s really transforming. When I think about what we did here (at Pilot+Projects). It’s nothing compared to what they’re doing.

Harm reduction with art as a focus. For unhoused people. It’s so much more challenging and so much more of a real accomplishment. They’re working with artists that can’t afford to have a studio. And are maybe unhoused.

Lane: Barely.

Chris: I’m lucky that I have been able to fucking afford to pay rent, you know because there’s been times when, if a class of mine doesn’t run at some college, then I’m, “Well, that’s money that I’m not gonna get.”

Final Thoughts

We left the conversation with an inescapable thought between us. What connects the sliding beads of closing artist-run spaces, the unhoused artists in Kensington, and the artists remaining housed by the barest of margins? All of us in different circumstances, affected by the same broad mechanizations of a select few. Waiting in trepidation for what the next petty-king will decide to do with the land beneath our feet, and the swamp and creeks beneath that.

I am honored to ink in the histories of Philadelphia, the glorious fable of Pilot+Projects, the gallery on the edge of a vast pit, the tale of the wizards of real estate, and the artist warriors. Their principles, dances, jests, and bravery in the face of certain death.

Perhaps it is better to accept the reality of endings, rather than cling to the fantasy of immortal art. Maybe by acknowledging our powerlessness over the future, we can build power and solidarity in the present.