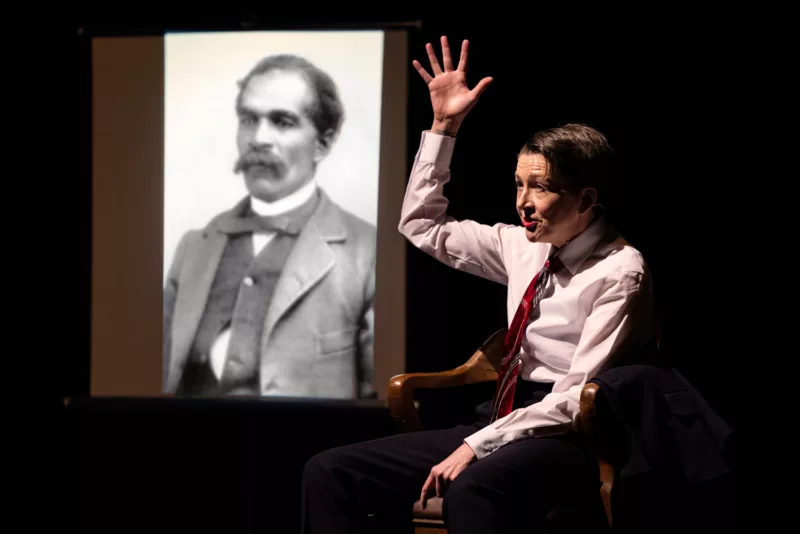

Sarah Kanouse, an artist, educator and parent, is touring a one-person multimedia performance titled, “My Electric Genealogy,” that she will present on Saturday, November 11th at 6PM at The Rotunda in West Philadelphia. In 75 minutes, Sarah switches personas between her grandfather, her grandmother, and versions of herself over the years. She will also introduce us to her extended family of power plants, substations and transmission towers.

The piece delves into her grandfather’s career in the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, exploring the history and repercussions of that fraught legacy. I read about her show and felt an immediate kinship. (See Endnotes below.) I also felt a deep curiosity about the piece and how it came about, and what we as artists can do to address the climate catastrophe. The other thing that caught my attention was reading that Sarah works in the field of Art Research. I wanted to find out more about each of these, so I contacted her. I came away from our conversation encouraged and with a resource and reading list that I share with you in the Endnotes.

I also had the pleasure of speaking with Daniel Tucker, who organized the Eco-Social Salon, Site-Seeing, and Screening Series that Sarah’s performance is part of. Daniel, Director of Museum Studies and Associate Professor at University of the Arts, told me he started the series to present the kinds of events he wanted to attend. As he explained it, “Infrastructure and climate need to be learned within a community. It takes a large skillset to understand them. This series is an invitation to be part of a collective.” Making Worlds Book Store and Social Center, the West Philly non-profit bookstore and social center, is a co-sponsor of the series, along with RAIR and The Green Sun. I encourage you to follow the impactful things all these people are working on.

Sarah currently teaches in the department of Art and Design at Northeastern University, Boston. She has an undergraduate degree in art from Yale University and an MFA in art and design from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. I was curious how she moved from visual art into performance, and two names came up: Rodney King and Anna Deavere Smith. Sarah is a multigenerational Angeleno. She attended the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts in the early 90s as a visual art major. The 1991 brutal beating of Rodney King by L.A. police officers was captured on videotape and broadcast nationally. The subsequent riots in 1992, after the acquittal of the police officers involved in the beating, occurred while she was in high school. A year later, she attended an early performance of “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992” by the actor and playwright Anna Deavere Smith. “Twilight” is a one-person show based on characters Smith developed from hundreds of interviews with people directly or indirectly connected to the L.A. uprising. Sarah told me that work resonated with her, but it wasn’t until years later that she understood how she could finally process what she had seen in Smith’s approach to a crisis: a form of art that engaged in research and processed information through body and voice to create compelling storytelling.

Other early experiences also opened her eyes to alternative ways to make art. Certain non-art courses at Yale allowed art students to respond to assignments with creative projects. Later she went on to work in the Midwest doing grassroots, community-based alternative media audio and visual projects. She told me it was during graduate school that she really started braiding visual art, activism and critical theory together, creating interdisciplinary films with a political dimension. Instead of starting with a particular medium, she figures out what medium is appropriate for the piece.

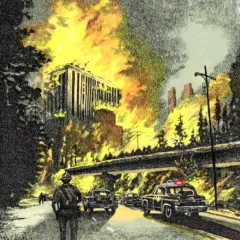

Sarah traces the beginning ideas for “My Electric Genealogy” and creating stories about place and landscape to her artist residency at Headlands Institute. While she was there, she had a startling and visceral reaction to a group prompt about climate change. At the time, her daughter was three years old. Sarah told me how she burst into tears thinking about global warming’s impact on her daughter’s future. She realized how different her own future had looked when she was younger. She also realized she was in a unique position of proximity to someone who had played a central role in electrifying Los Angeles. As her exploration developed, she interviewed family members and visited archives in her attempt to understand her family’s involvement in the future that was being stolen from her daughter’s generation. In writing about her performance Sarah summarizes it this way:

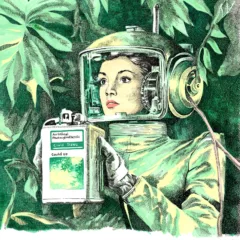

“For nearly forty years my grandfather designed, planned, and supervised the spider-vein network of lines connecting Los Angeles to its distant sources of electric power. From the 1930s to the 1970s, he made a second family of the grid and its substations, converter stations, and interties, photographing these monuments of the modern everyday with one foot in the aesthetic and another in the techno-scientific sublime.”

The artist also mentions that finding her grandfather’s photographs of transformers etc., mixed in with photos of family holidays and celebrations, made them feel like they were part of her family.

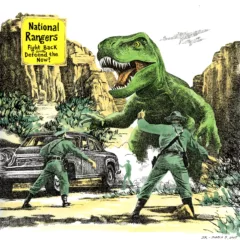

The work took years to develop. Through research, interviews and by looking at the familiar with a different perspective, Sarah investigated how the culture and politics of the early and mid-20th century supported the voracious need for and production of electricity. It fed the utopian vision of the future held by her grandfather, his colleagues and his generation. Sarah learned that to reach the goals of creating a system to supply LA with bountiful and dependable electricity, sacrifices were made, often by people who had no say in the matter. In her research she discovered how communities and habitats far from L.A. were affected by the implementation of “carbon-heavy infrastructures.” The piece details this and shows what the ongoing consequences are. (See resources in the Endnotes)

Sarah has performed the piece a number of times around the country. I was curious if it changes from venue to venue. She told me that would be difficult because it’s based on a 40-page script with tons of media cues for video and still images. There is also an elaborate audio score by Jacob Ross and Beau Kenyon, and she worked with the Philadelphia-based choreographer Esther Baker-Tarpaga on movement and stances that echo transmission towers.

After our long, eye-opening conversation, I wondered how the piece ends. Does she offer a solution? Sarah told me it ends with the possibility for repair. It’s less about proposing solutions. The climate crisis demands that we rethink everything, and with this work she is trying to model a new language and ways of thinking. She pointed me in the direction of two influences, which I will pass along: the work of Arturo Escobar, a Columbian-American anthropologist, and Laura Rendon’s book, “Sentipensante (Sensing / Thinking) Pedagogy.”

And one final note. I was talking to my Artblog colleague Martina Merlo about Sarah’s upcoming show. Martina said that if she visits artists, and they’re not making work about climate change, she asks, ‘Why not?’

“My Electric Genealogy”

Saturday November 11th, 2023, at 6pm

The Rotunda (4014 Walnut St, Philadelphia, PA 19104)

FREE. Register here.

_____________

Endnotes by the author

1. Four out of six of my primary family members worked in either nuclear power or fossil fuel power generation. My mother and I were the holdouts. She wrote poetry and I dropped out of college for a year and a half and joined New England Commedia, a traveling theater company that performed commedia dell’arte socio-political satires, which included critiques of the nuclear power industry. When I eventually returned to college, I produced and performed in the world premiere of Ed Sanders’s “The Karen Silkwood Cantata” before deciding to become a visual arts major.

2. In response to my questions about artistic research, Sarah mentioned a number of people to look into who are also engaged in compelling critical storytelling, such as Deke Weaver, Sam Green, Ashley Hunt, Renée Green and Claire Bishop.

3. Sarah provided these links to organizations she spoke with that are working for environmental justice for Navajo communities that have been affected by energy and environmental issues:

Tó Nizhóní Ání and Diné C.A.R.E.

4. Coincidentally, I came across this quote by the writer and scholar Clint Smith, that I think beautifully supports Sarah’s approach:

“Our lives are defined by that love, that joy, that laughter, but also by anxiety, fear, despair. And somewhere between those is, I think, a responsibility: recognizing the truth of our past and all that has preceded us, not in a way that’s meant to paralyze us or overwhelm us or trap us in a sense of despair, but in a way that is meant to help us recognize and remember our own agency.”